Reading comprehension strategies in the classroom

What reading comprehension strategies are most effective in the classroom? A brief look at the complex act of reading.

Reading comprehension strategies are a set of techniques that guide readers to better understand and interpret text. These strategies are not just about reading words on a page, but about deeply engaging with the content to extract meaning and build knowledge. They are the cognitive processes that readers use to make sense of what they read.

According to McNamara's book, effective reading comprehension strategies are key to improving the ability to comprehend text. These strategies can be seen as tools in a reader's toolbox, similar to writing scaffolds, each serving a different purpose and being used at different stages of the reading process, from early comprehension through advanced analysis.

One of the key aspects of reading comprehension strategies is the active engagement of the reader with the text. This means that readers are not just passively reading the words, but are actively thinking about the content, asking questions, making predictions, and connecting the information to their existing knowledge.

This active engagement is what allows readers to deeply understand and remember the information they read.

For example, a common reading comprehension strategy is summarization, where readers are encouraged to put the information they read into their own words. This not only helps to ensure that they have understood the information, whether working with complex texts or basic sight words, but also helps to consolidate their understanding and make the information easier to remember.

As Perfetti et al. pointed out, understanding the many components of reading comprehension, including the use of effective strategies, can aid in the formulation of specific hypotheses about reading expertise and reading difficulties.

In a study on transactional instruction of reading comprehension strategies, it was found that teaching students to use a variety of strategies can improve their comprehension skills. This highlights the importance of teaching students not just to read, but to use strategies to understand what they read.

In conclusion, reading comprehension strategies are an essential part of effective reading instruction. They help students to engage deeply with the text, understand and remember the information, and apply it to their own lives.

Key Insights:

In the quest for effective reading , research and practice have identified a number of approaches that have proven successful in aiding students to better understand and retain the information they read. Here are nine such strategies:

These strategies, when used effectively, can significantly enhance students' reading comprehension skills. As Dr. Danielle S. McNamara states, "Comprehension is a complex process that involves knowledge, experience, thinking and teaching. The right strategies can make a significant difference in a student's understanding."

Key Insights:

The most effective reading comprehension strategies include activating prior knowledge, visualization, summarization, and reciprocal teaching. These evidence-based techniques transform struggling readers into confident comprehenders by promoting active engagement with text. Research shows that activating prior knowledge is the single most powerful strategy for improving comprehension outcomes.

In a recent study, we examined the influence of thinking strategies on EFL learners’ reading comprehension levels through the Think Aloud strategy. The purposes were to investigate whether good and poor comprehenders who had got prior strategy instruction would achieve the same results in a reading comprehension test, generate further insights into the nature of the reading processes, and develop outlines for improving the practice of teaching reading comprehension based on a better understanding of the reading processes of good and poor comprehenders of expository writing.

Findings indicated that good and poor comprehenders may use the same total number of cognitive strategies while performing a reading task, but they differ in their reasoning and utilization of comprehension monitoring strategies when responding to passages of different lengths.

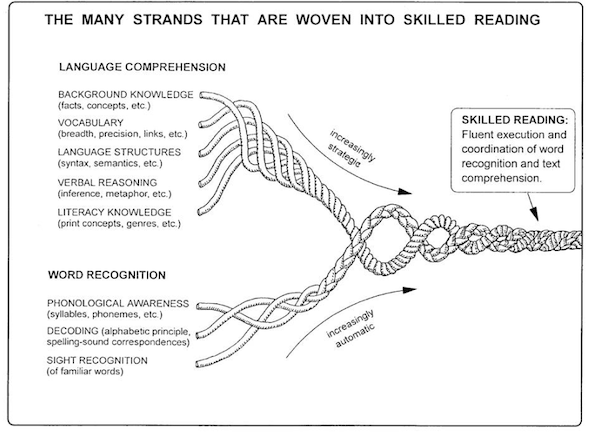

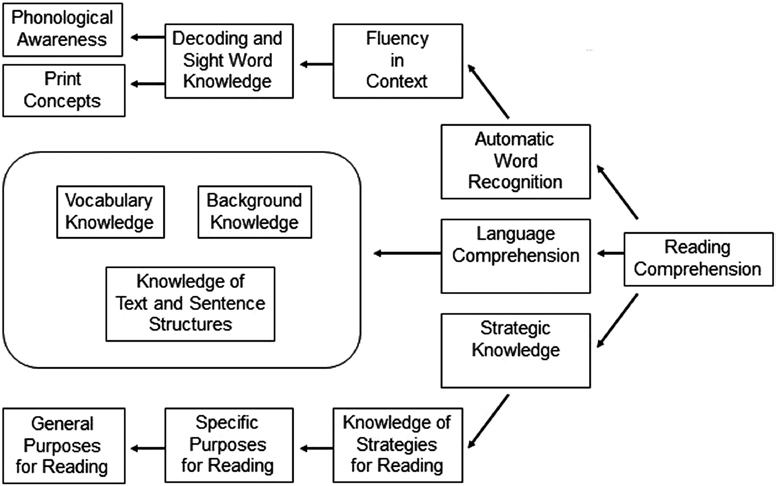

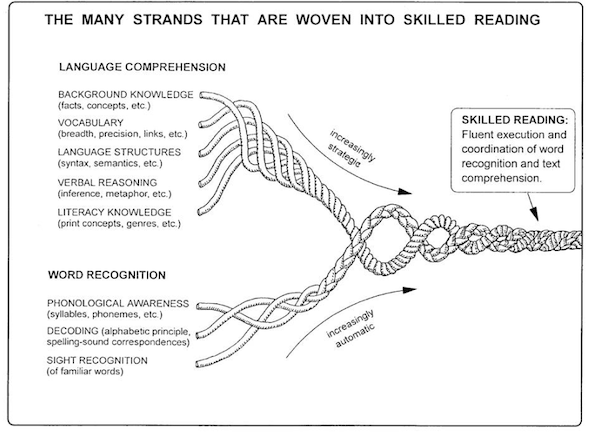

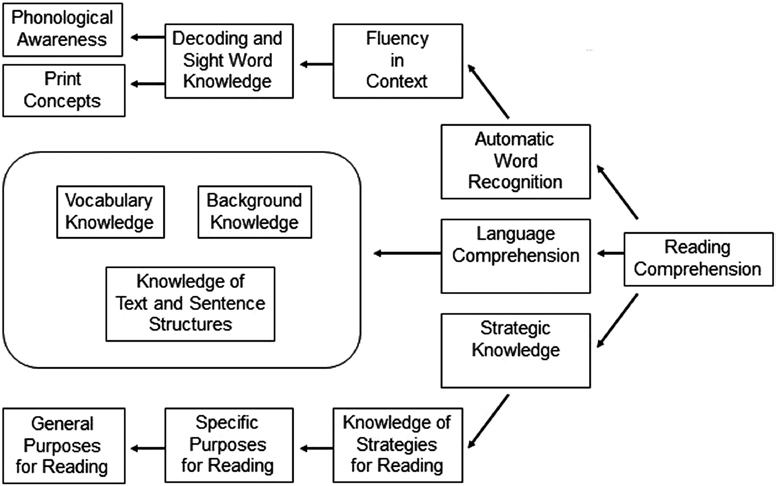

The interactive model combines bottom-up processing (decoding words) with top-down processing (using background knowledge and context). This revolutionary approach changes how teachers structure reading instruction by balancing phonics skills with meaning-making strategies. Understanding these dual processes helps educators address both word recognition and comprehension simultaneously.

There are various models of the reading process: bottom-up, top-down, and interactive models. In bottom-up models, the reader must account for the visual information individually before assigning meaning to any printed string of letters (Holmes, 1970 [1]; Laberge and Samuels, 1974 [2]; and Gough, 1972 [3]). While in the top-down models, the reader is guided by his expectations about what is on the printed page (Goodman, 1970 [4]; Smith 1971[5]). On the other hand, interactive models of reading involve bottom-up and top-down processes that influence the text processing and the reader’s interpretation of the text. The interactive models proposed by Rumelhart (1977) [6], and Stanovich (1980) [7], emphasize the interaction process between the reader and his prior experience or background knowledge and the text.

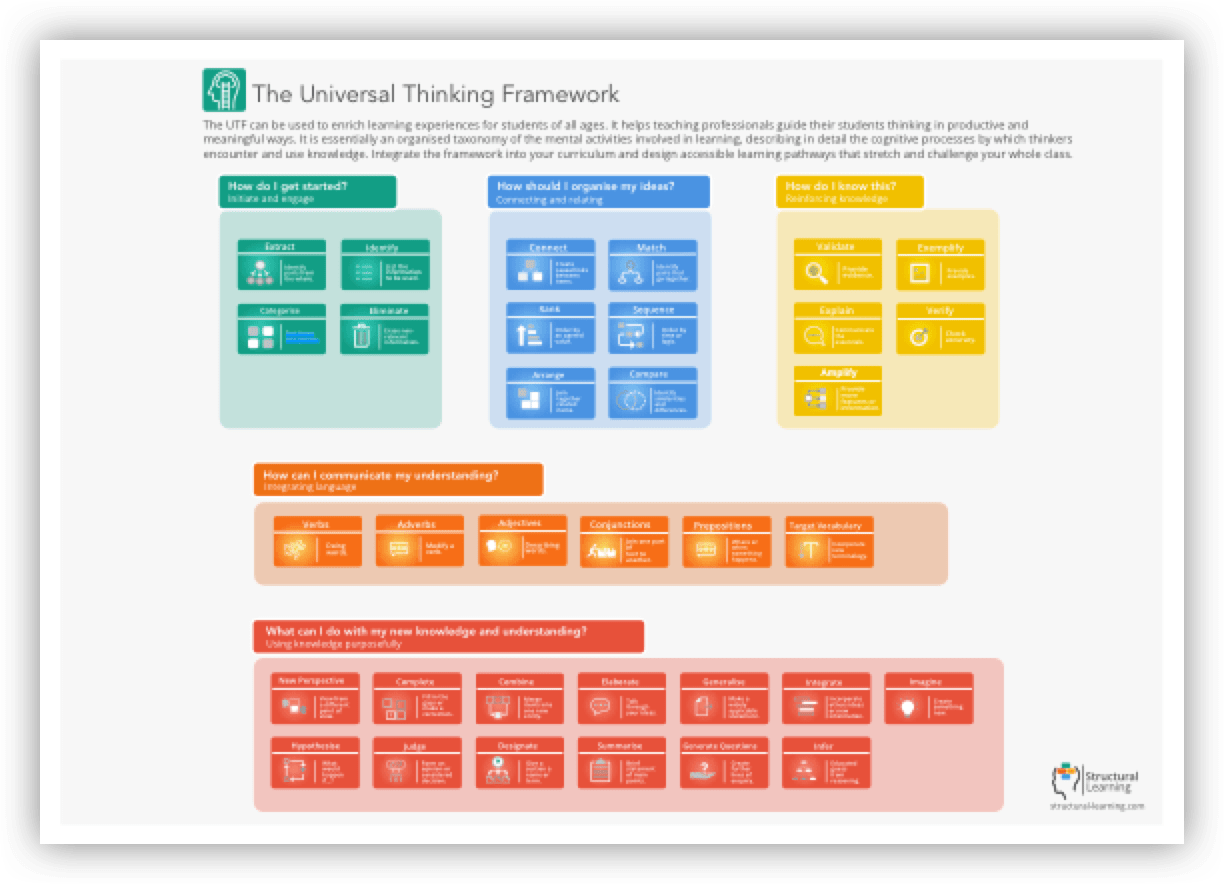

Reading comprehension strategies are classified into cognitive processes that occur before, during, and after reading. Pre-reading strategies include activating prior knowledge and making predictions, while during-reading strategies involve questioning and visualizing. Post-reading strategies focus on summarizing, reflecting, and connecting ideas to broader knowledge.

There are numerous thinking strategies that schools can adopt in their never to advance the ability of readers. Whether you are focusing on low-level readers or trying to advance skilled readers with extra challenge, the list below is a good starting point for thinking about comprehension skills.

1. Active awareness of strategies

2. Lack of awareness of strategies

3. Accepting ambiguity

4. Establishing intra-sentential ties

5. Establishing inter-sentential ties

6. Using background knowledge

Effective study methods for reading comprehension include structured note-taking, reciprocal teaching, and guided practice with feedback. Students benefit most from explicit instruction followed by gradual release of responsibility. Regular assessment and adjustment of strategies ensures sustained improvement in comprehension skills.

In this study, participants were given a reading pre-test, the purpose of which was to determine who were good and who were the poor comprehenders. The former were those whose scores were above the median score, while the latter were those whose scores were below the median score. After the reading test, the participants took the test (a cloze test) to solve; they were asked to think aloud and record what they did to find the suitable word they decided to put in the blank. Later, they were asked to recall what they remembered from the cloze test and write it in their own words.

Good and poor readers differed in terms of frequency of usage of six of the strategies they used.

Good readers reported using the Rereading Strategy, Paraphrasing, and Reading Subsequent Text more often than poor readers; they used strategies from categories D (Establishing Intra-sentential Ties) and E (Establishing Inter-sentential Ties).

On the other hand, poor readers reported using Looking for Key Vocabulary or Phrase and Using Prior Knowledge more significantly than good readers. Looking for Vocabulary or Phrases and Rereading Strategy indicated that poor readers face more semantic structural difficulty in solving the cloze test.

Further analysis indicated that poor readers who focused on Using Key Vocabulary or Phrases were those whose achievement scores in the reading comprehension pre-test were less than 4/20, those who used inadequate strategies when they confronted vocabulary problems. Whereas, good readers were more consistent in their ability to abstract relevant information the thing that led to better achievement scores.

Readers repeatedly used a range of strategies that they felt comfortable with, and did not try to use the other strategies actively although they knew them.

The overwhelming choices of effective comprehension strategy instruction for the low-level readers were Rereading, Paraphrasing and Reading Subsequent Text, while those for the poor readers were Looking for Key Vocabulary and Using Prior Knowledge.

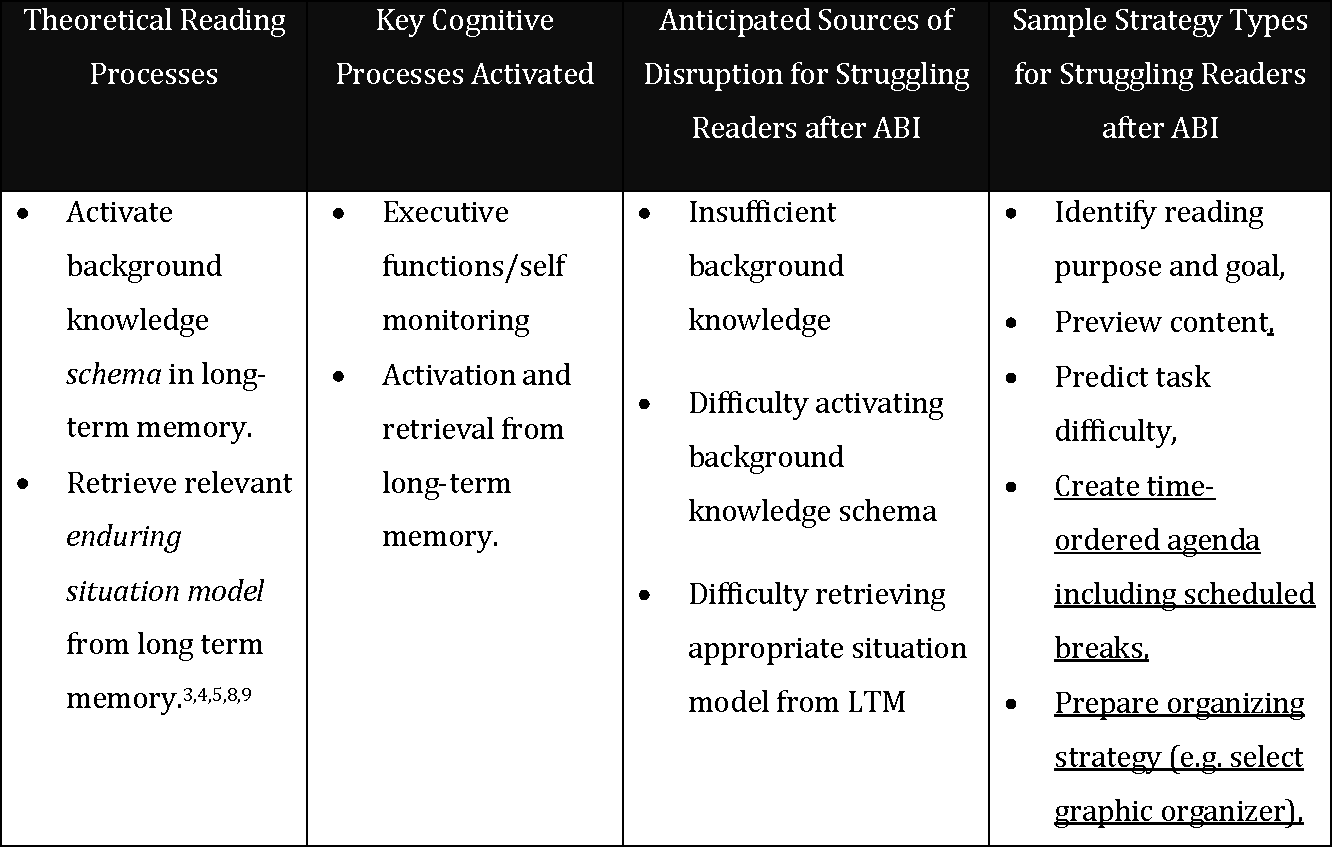

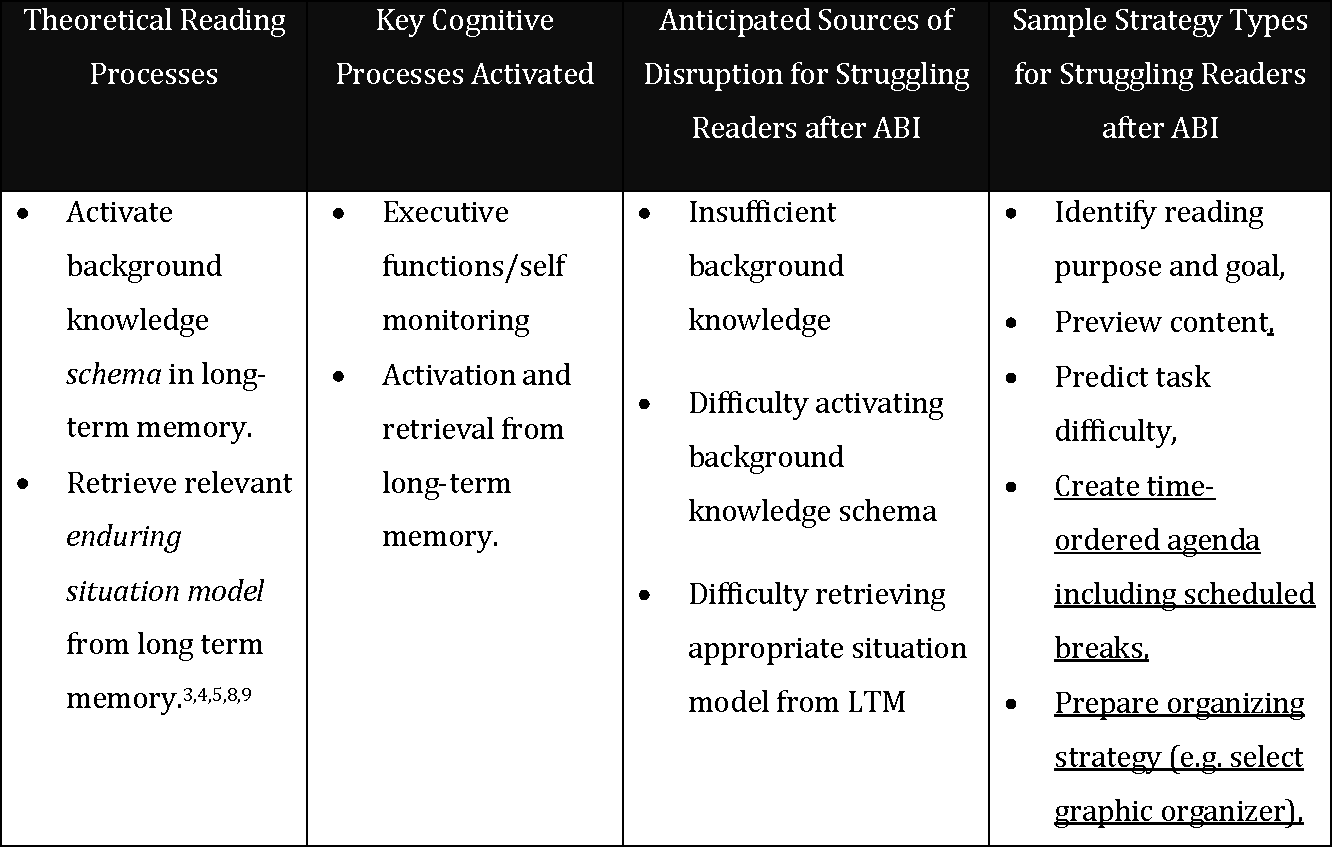

Background knowledge serves as the foundation for all reading comprehension, allowing readers to make connections and inferences. Students with relevant prior knowledge comprehend text significantly better than those without, even when reading ability is equivalent. Activating and building background knowledge before reading transforms comprehension outcomes more than any other single strategy.

The role of background knowledge in comprehension is a well-established concept in educational research. Here are seven ways that background knowledge contributes to comprehension, particularly in the context of reading:

In conclusion, background knowledge plays a pivotal role in reading comprehension. It not only aids in understanding the literal meaning of the text but also facilitates deeper, more critical thinking about the content. As educators, it is crucial to consider ways to build and activate students' background knowledge to support their reading comprehension.

Key Insights:

Students struggle with comprehension strategies when they lack metacognitive awareness and fail to monitor their understanding actively. The strategy paradox shows that knowing strategies is insufficient without understanding when and how to apply them effectively. Poor readers often use strategies passively rather than engaging in the active thinking processes that characterize skilled comprehension.

The study showed that both good and poor readers repeatedly used strategies that they felt comfortable with, and did not try to use the other strategies actively although they knew them.

It also indicated that bottom-up processors or non-risk takers were more from poor readers than good readers.

Although both good and poor comprehenders used a limited number of strategies, good comprehenders appeared to have greater ability to control their strategy use by using the correct strategy type with the suitable stimulus sentence, and changing the types of strategies when they felt the need to.

The study could also bring forward the students’ changing behaviours while responding to different types of questions. Subjects from both groups expressed non-preference to solve true/false statements and a tendency to solve them haphazardly when they ran out of time.

Effective comprehension strategy instruction must move students beyond passive reading to active engagement with text. Teachers should focus on teaching students how to coordinate multiple strategies rather than simply introducing individual techniques. The ultimate goal is developing independent readers who can monitor and adjust their comprehension processes automatically.

From this study, a number of conclusions can be drawn. Most importantly, before commencing instruction, teachers should do pre-reading assessment tests as early as the beginning of the academic year and occasionally when the need arises to recognize the mixed ability groups they are teaching and thus adapt their teaching to address those groups’ needs. In addition, they should make sure that instruction is student-centred, classroom situations shaped accordingly, and poor comprehenders should be dealt with differently than good comprehenders by varying the teaching approaches and promoting an environment of information exchange.

Moreover, educators may need to reassess their methods of teaching reading comprehension strategies. Consequently, strategies that are used by good comprehenders and prove to lead to successful comprehension might be taught to poor comprehenders through suitable contexts of reading situations. Poor comprehenders should be trained to use those strategies actively to get control over them and be able to use them independently.

Educators should also pay special attention to the top-down, bottom-up, and interactive types of readers as well as styles of learning and accommodate their teaching to address those types. They may, for example, focus on teaching the usage of bottom-up strategies when they are interested in developing grammatical knowledge and vocabulary building for ESL learners. Related activities should be evaluated, and teachers can model the procedures for responding to situations that require particular reasoning strategies. Varying the teaching approach becomes an important element of active classrooms where all students participate and thus learn regardless of their abilities.

When it comes to testing and assessment, teachers should be aware of the importance of both formative and summative assessment. When assessing formatively, test formats should be varied (standardized multiple-choice tests, true/false statements, matching exercises, Short essay questions, etc.) Before giving a test, teachers should provide practice on the attacking skills required for each type of tests. Based on formative test results, teachers should be able to assess where in the cycle of teaching, reviewing, testing, revisiting they stand and act accordingly. Revision becomes a main practice after formative tests and before summative tests.

Teachers should prioritize activating prior knowledge before reading and explicitly model comprehension strategies during guided instruction. Implement reciprocal teaching and provide regular opportunities for students to practice strategy coordination with feedback. Focus on developing metacognitive awareness so students learn to monitor their own understanding and adjust strategies when needed.

First, since curricular content is always imposed on teachers indirectly through textbook adoption, and since the scope and amount of material is larger than any teacher could cover, experienced teachers need to select the most suitable materials that address their students’ interests and abilities in the condition that they sustain the curriculum scope. Second, they may also adapt the sequence of instruction for the same purposes. On the other hand, less experienced and in-service teachers should seek support from more knowledgeable subject coordinators whenever they need it.

Also under the coordinators’ supervision, teachers should be involved in the process of developing their own skills through sustained training, information exchange, and action research focused on successes and failures. The teaching of comprehension is complex and different education communities bring their own ideas to the table. Whether you are adopting explicit instruction approaches or trying to immerse learners into rich language environments, the ability of readers is affected by a multitude of areas that need to be woven into a comprehensive approach with adequate time for practice.

Nahida El Assi, Associate Professor

Program developer, teacher trainer, materials writer, researcher, lecturer

LinkedIn: https://ca.linkedin.com/in/nahidaelassionline

Webpage: www.edempowerment.space

McNamara's research and other evidence-based studies demonstrate the effectiveness of active comprehension strategy instruction. Multiple peer-reviewed studies confirm that explicit strategy teaching improves reading outcomes across diverse student populations. The research consistently shows that strategy coordination and metacognitive awareness are more important than the number of strategies students know.

[1] Holmes, H. W. 1970. Handbook of Research, Vol. 1. Pearson, D. (Eds.) (2002).

[2] La Berge and Samuels 1974. Reading in a second language: a reading problem or a language problem? Journal of College Reading and Learning (2003).

[3] Gough, P. B. 1972. “One second of reading.” In J. F. Kavanagh and I. G. Mattingly (Eds.). Language by ear and eye (PP. 332-358). Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

[4] Goodman, K. S. 1970. Reading: a psycholinguistic guessing game”. Reading Research Quarterly, 5/1970, 402-426.

[5] Smith, H. 1971. The responses of good and poor readers when asked to read for different purposes. Reading Research Quarterly, 11/1, 53-83.

[6] Rumelhart, D.E.1977.Toward an interactive model of reading. NJ: Erlbaum

[7] Stanovich, K. E. (1980). Toward an interactive-compensatory model of individual differences in the development of reading fluency. Reading Research Quarterly, 16, 32-71.

Reading comprehension strategies are a set of techniques that guide readers to better understand and interpret text. These strategies are not just about reading words on a page, but about deeply engaging with the content to extract meaning and build knowledge. They are the cognitive processes that readers use to make sense of what they read.

According to McNamara's book, effective reading comprehension strategies are key to improving the ability to comprehend text. These strategies can be seen as tools in a reader's toolbox, similar to writing scaffolds, each serving a different purpose and being used at different stages of the reading process, from early comprehension through advanced analysis.

One of the key aspects of reading comprehension strategies is the active engagement of the reader with the text. This means that readers are not just passively reading the words, but are actively thinking about the content, asking questions, making predictions, and connecting the information to their existing knowledge.

This active engagement is what allows readers to deeply understand and remember the information they read.

For example, a common reading comprehension strategy is summarization, where readers are encouraged to put the information they read into their own words. This not only helps to ensure that they have understood the information, whether working with complex texts or basic sight words, but also helps to consolidate their understanding and make the information easier to remember.

As Perfetti et al. pointed out, understanding the many components of reading comprehension, including the use of effective strategies, can aid in the formulation of specific hypotheses about reading expertise and reading difficulties.

In a study on transactional instruction of reading comprehension strategies, it was found that teaching students to use a variety of strategies can improve their comprehension skills. This highlights the importance of teaching students not just to read, but to use strategies to understand what they read.

In conclusion, reading comprehension strategies are an essential part of effective reading instruction. They help students to engage deeply with the text, understand and remember the information, and apply it to their own lives.

Key Insights:

In the quest for effective reading , research and practice have identified a number of approaches that have proven successful in aiding students to better understand and retain the information they read. Here are nine such strategies:

These strategies, when used effectively, can significantly enhance students' reading comprehension skills. As Dr. Danielle S. McNamara states, "Comprehension is a complex process that involves knowledge, experience, thinking and teaching. The right strategies can make a significant difference in a student's understanding."

Key Insights:

The most effective reading comprehension strategies include activating prior knowledge, visualization, summarization, and reciprocal teaching. These evidence-based techniques transform struggling readers into confident comprehenders by promoting active engagement with text. Research shows that activating prior knowledge is the single most powerful strategy for improving comprehension outcomes.

In a recent study, we examined the influence of thinking strategies on EFL learners’ reading comprehension levels through the Think Aloud strategy. The purposes were to investigate whether good and poor comprehenders who had got prior strategy instruction would achieve the same results in a reading comprehension test, generate further insights into the nature of the reading processes, and develop outlines for improving the practice of teaching reading comprehension based on a better understanding of the reading processes of good and poor comprehenders of expository writing.

Findings indicated that good and poor comprehenders may use the same total number of cognitive strategies while performing a reading task, but they differ in their reasoning and utilization of comprehension monitoring strategies when responding to passages of different lengths.

The interactive model combines bottom-up processing (decoding words) with top-down processing (using background knowledge and context). This revolutionary approach changes how teachers structure reading instruction by balancing phonics skills with meaning-making strategies. Understanding these dual processes helps educators address both word recognition and comprehension simultaneously.

There are various models of the reading process: bottom-up, top-down, and interactive models. In bottom-up models, the reader must account for the visual information individually before assigning meaning to any printed string of letters (Holmes, 1970 [1]; Laberge and Samuels, 1974 [2]; and Gough, 1972 [3]). While in the top-down models, the reader is guided by his expectations about what is on the printed page (Goodman, 1970 [4]; Smith 1971[5]). On the other hand, interactive models of reading involve bottom-up and top-down processes that influence the text processing and the reader’s interpretation of the text. The interactive models proposed by Rumelhart (1977) [6], and Stanovich (1980) [7], emphasize the interaction process between the reader and his prior experience or background knowledge and the text.

Reading comprehension strategies are classified into cognitive processes that occur before, during, and after reading. Pre-reading strategies include activating prior knowledge and making predictions, while during-reading strategies involve questioning and visualizing. Post-reading strategies focus on summarizing, reflecting, and connecting ideas to broader knowledge.

There are numerous thinking strategies that schools can adopt in their never to advance the ability of readers. Whether you are focusing on low-level readers or trying to advance skilled readers with extra challenge, the list below is a good starting point for thinking about comprehension skills.

1. Active awareness of strategies

2. Lack of awareness of strategies

3. Accepting ambiguity

4. Establishing intra-sentential ties

5. Establishing inter-sentential ties

6. Using background knowledge

Effective study methods for reading comprehension include structured note-taking, reciprocal teaching, and guided practice with feedback. Students benefit most from explicit instruction followed by gradual release of responsibility. Regular assessment and adjustment of strategies ensures sustained improvement in comprehension skills.

In this study, participants were given a reading pre-test, the purpose of which was to determine who were good and who were the poor comprehenders. The former were those whose scores were above the median score, while the latter were those whose scores were below the median score. After the reading test, the participants took the test (a cloze test) to solve; they were asked to think aloud and record what they did to find the suitable word they decided to put in the blank. Later, they were asked to recall what they remembered from the cloze test and write it in their own words.

Good and poor readers differed in terms of frequency of usage of six of the strategies they used.

Good readers reported using the Rereading Strategy, Paraphrasing, and Reading Subsequent Text more often than poor readers; they used strategies from categories D (Establishing Intra-sentential Ties) and E (Establishing Inter-sentential Ties).

On the other hand, poor readers reported using Looking for Key Vocabulary or Phrase and Using Prior Knowledge more significantly than good readers. Looking for Vocabulary or Phrases and Rereading Strategy indicated that poor readers face more semantic structural difficulty in solving the cloze test.

Further analysis indicated that poor readers who focused on Using Key Vocabulary or Phrases were those whose achievement scores in the reading comprehension pre-test were less than 4/20, those who used inadequate strategies when they confronted vocabulary problems. Whereas, good readers were more consistent in their ability to abstract relevant information the thing that led to better achievement scores.

Readers repeatedly used a range of strategies that they felt comfortable with, and did not try to use the other strategies actively although they knew them.

The overwhelming choices of effective comprehension strategy instruction for the low-level readers were Rereading, Paraphrasing and Reading Subsequent Text, while those for the poor readers were Looking for Key Vocabulary and Using Prior Knowledge.

Background knowledge serves as the foundation for all reading comprehension, allowing readers to make connections and inferences. Students with relevant prior knowledge comprehend text significantly better than those without, even when reading ability is equivalent. Activating and building background knowledge before reading transforms comprehension outcomes more than any other single strategy.

The role of background knowledge in comprehension is a well-established concept in educational research. Here are seven ways that background knowledge contributes to comprehension, particularly in the context of reading:

In conclusion, background knowledge plays a pivotal role in reading comprehension. It not only aids in understanding the literal meaning of the text but also facilitates deeper, more critical thinking about the content. As educators, it is crucial to consider ways to build and activate students' background knowledge to support their reading comprehension.

Key Insights:

Students struggle with comprehension strategies when they lack metacognitive awareness and fail to monitor their understanding actively. The strategy paradox shows that knowing strategies is insufficient without understanding when and how to apply them effectively. Poor readers often use strategies passively rather than engaging in the active thinking processes that characterize skilled comprehension.

The study showed that both good and poor readers repeatedly used strategies that they felt comfortable with, and did not try to use the other strategies actively although they knew them.

It also indicated that bottom-up processors or non-risk takers were more from poor readers than good readers.

Although both good and poor comprehenders used a limited number of strategies, good comprehenders appeared to have greater ability to control their strategy use by using the correct strategy type with the suitable stimulus sentence, and changing the types of strategies when they felt the need to.

The study could also bring forward the students’ changing behaviours while responding to different types of questions. Subjects from both groups expressed non-preference to solve true/false statements and a tendency to solve them haphazardly when they ran out of time.

Effective comprehension strategy instruction must move students beyond passive reading to active engagement with text. Teachers should focus on teaching students how to coordinate multiple strategies rather than simply introducing individual techniques. The ultimate goal is developing independent readers who can monitor and adjust their comprehension processes automatically.

From this study, a number of conclusions can be drawn. Most importantly, before commencing instruction, teachers should do pre-reading assessment tests as early as the beginning of the academic year and occasionally when the need arises to recognize the mixed ability groups they are teaching and thus adapt their teaching to address those groups’ needs. In addition, they should make sure that instruction is student-centred, classroom situations shaped accordingly, and poor comprehenders should be dealt with differently than good comprehenders by varying the teaching approaches and promoting an environment of information exchange.

Moreover, educators may need to reassess their methods of teaching reading comprehension strategies. Consequently, strategies that are used by good comprehenders and prove to lead to successful comprehension might be taught to poor comprehenders through suitable contexts of reading situations. Poor comprehenders should be trained to use those strategies actively to get control over them and be able to use them independently.

Educators should also pay special attention to the top-down, bottom-up, and interactive types of readers as well as styles of learning and accommodate their teaching to address those types. They may, for example, focus on teaching the usage of bottom-up strategies when they are interested in developing grammatical knowledge and vocabulary building for ESL learners. Related activities should be evaluated, and teachers can model the procedures for responding to situations that require particular reasoning strategies. Varying the teaching approach becomes an important element of active classrooms where all students participate and thus learn regardless of their abilities.

When it comes to testing and assessment, teachers should be aware of the importance of both formative and summative assessment. When assessing formatively, test formats should be varied (standardized multiple-choice tests, true/false statements, matching exercises, Short essay questions, etc.) Before giving a test, teachers should provide practice on the attacking skills required for each type of tests. Based on formative test results, teachers should be able to assess where in the cycle of teaching, reviewing, testing, revisiting they stand and act accordingly. Revision becomes a main practice after formative tests and before summative tests.

Teachers should prioritize activating prior knowledge before reading and explicitly model comprehension strategies during guided instruction. Implement reciprocal teaching and provide regular opportunities for students to practice strategy coordination with feedback. Focus on developing metacognitive awareness so students learn to monitor their own understanding and adjust strategies when needed.

First, since curricular content is always imposed on teachers indirectly through textbook adoption, and since the scope and amount of material is larger than any teacher could cover, experienced teachers need to select the most suitable materials that address their students’ interests and abilities in the condition that they sustain the curriculum scope. Second, they may also adapt the sequence of instruction for the same purposes. On the other hand, less experienced and in-service teachers should seek support from more knowledgeable subject coordinators whenever they need it.

Also under the coordinators’ supervision, teachers should be involved in the process of developing their own skills through sustained training, information exchange, and action research focused on successes and failures. The teaching of comprehension is complex and different education communities bring their own ideas to the table. Whether you are adopting explicit instruction approaches or trying to immerse learners into rich language environments, the ability of readers is affected by a multitude of areas that need to be woven into a comprehensive approach with adequate time for practice.

Nahida El Assi, Associate Professor

Program developer, teacher trainer, materials writer, researcher, lecturer

LinkedIn: https://ca.linkedin.com/in/nahidaelassionline

Webpage: www.edempowerment.space

McNamara's research and other evidence-based studies demonstrate the effectiveness of active comprehension strategy instruction. Multiple peer-reviewed studies confirm that explicit strategy teaching improves reading outcomes across diverse student populations. The research consistently shows that strategy coordination and metacognitive awareness are more important than the number of strategies students know.

[1] Holmes, H. W. 1970. Handbook of Research, Vol. 1. Pearson, D. (Eds.) (2002).

[2] La Berge and Samuels 1974. Reading in a second language: a reading problem or a language problem? Journal of College Reading and Learning (2003).

[3] Gough, P. B. 1972. “One second of reading.” In J. F. Kavanagh and I. G. Mattingly (Eds.). Language by ear and eye (PP. 332-358). Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

[4] Goodman, K. S. 1970. Reading: a psycholinguistic guessing game”. Reading Research Quarterly, 5/1970, 402-426.

[5] Smith, H. 1971. The responses of good and poor readers when asked to read for different purposes. Reading Research Quarterly, 11/1, 53-83.

[6] Rumelhart, D.E.1977.Toward an interactive model of reading. NJ: Erlbaum

[7] Stanovich, K. E. (1980). Toward an interactive-compensatory model of individual differences in the development of reading fluency. Reading Research Quarterly, 16, 32-71.