Operant Conditioning

What is operant conditioning and what is its relevance for classroom behaviour management?

What is operant conditioning and what is its relevance for classroom behaviour management?

Tracing its origins back to the early 20th century, operant conditioning is a fundamental concept within behavioral psychology, providing a framework for understanding how our actions are shaped by their consequences. As you're about to explore the intricacies of operant conditioning, it's like unlocking a door to the understanding of behaviour. In 2025, these principles remain as relevant as ever for educators seeking evidence-based approaches to classroom management.

laid the cornerstone for a systematic approach to studying behavior, making him one of the most influential psychologists of his time. His theories continue to resonate in psychology and education, inviting both accolades and debate. The article ahead explores Skinner's contributions and the experiments that transformed our understanding of behaviour.

Reward or consequence? This dilemma plays a central role in operant conditioning through concepts such as reinforcement and punishment. Whether enhancing learning environments or modifying behaviour, the application of these principles is vast and nuanced. With positive and negative reinforcements and punishments shaping complex behaviours, you're poised to explore strategies for influence and change. Prepare to examine the mechanisms of behaviour modification in the sprawling landscape of reinforcement theory.

Operant conditioning is a learning process where behaviors are modified through consequences like rewards or punishments. When a behavior is followed by a positive outcome, it's more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by negative outcomes tend to decrease. This principle explains how we learn from the results of our actions in everyday life.

Operant conditioning is a fundamental theory in , originally established by notable psychologist B.F. Skinner during the 1930s. This theory proposes a connection between behaviours and their subsequent consequences, which are categorised as either reinforcers or punishers. Reinforcers are outcomes that increase the likelihood of a behaviour recurring, while punishers decrease its occurrence. This dynamic is central to the process of learning and behaviour modification.

Behaviour, in the context of operant conditioning, is influenced by the reinforcement schedules used. These schedules determine the timing and regularity of reinforcements, shaping both simple and complex behaviours over time.

Skinner's focus on observable and measurable responses led him to devise experiments, particularly with animals, that demonstrated the power of environmental changes to alter behaviours. Using tools like the operant conditioning chamber, Skinner was able to carefully control the stimuli and consequent responses, thereby providing strong support for his theory.

At its core, operant conditioning involves a stimulus that elicits a voluntary behaviour, which is then followed by a consequence. Reinforcers used to shape behaviour can be primary, such as food or drink, secondary, like verbal praise, or generalised, involving like money.

Operant conditioning works by creating associations between voluntary behaviors and their consequences. When a behavior leads to a desirable outcome (reinforcement), the behavior becomes stronger and more frequent. Conversely, when a behavior leads to an undesirable outcome (punishment), it becomes weaker and less frequent.

Operant conditioning explores reversible behaviour that's "controlled" by consequences. At the heart of this learning model lies the principle that behaviours which are reinforced tend to be repeated, increasing the probability of those behaviours being exhibited in the future. Conversely, behaviours that are met with punishment are less likely to reoccur.

Operant conditioning emphasises the relationship between behaviours and their resulting effects, whether behaviours are encouraged with positive outcomes or discouraged by undesirable results.

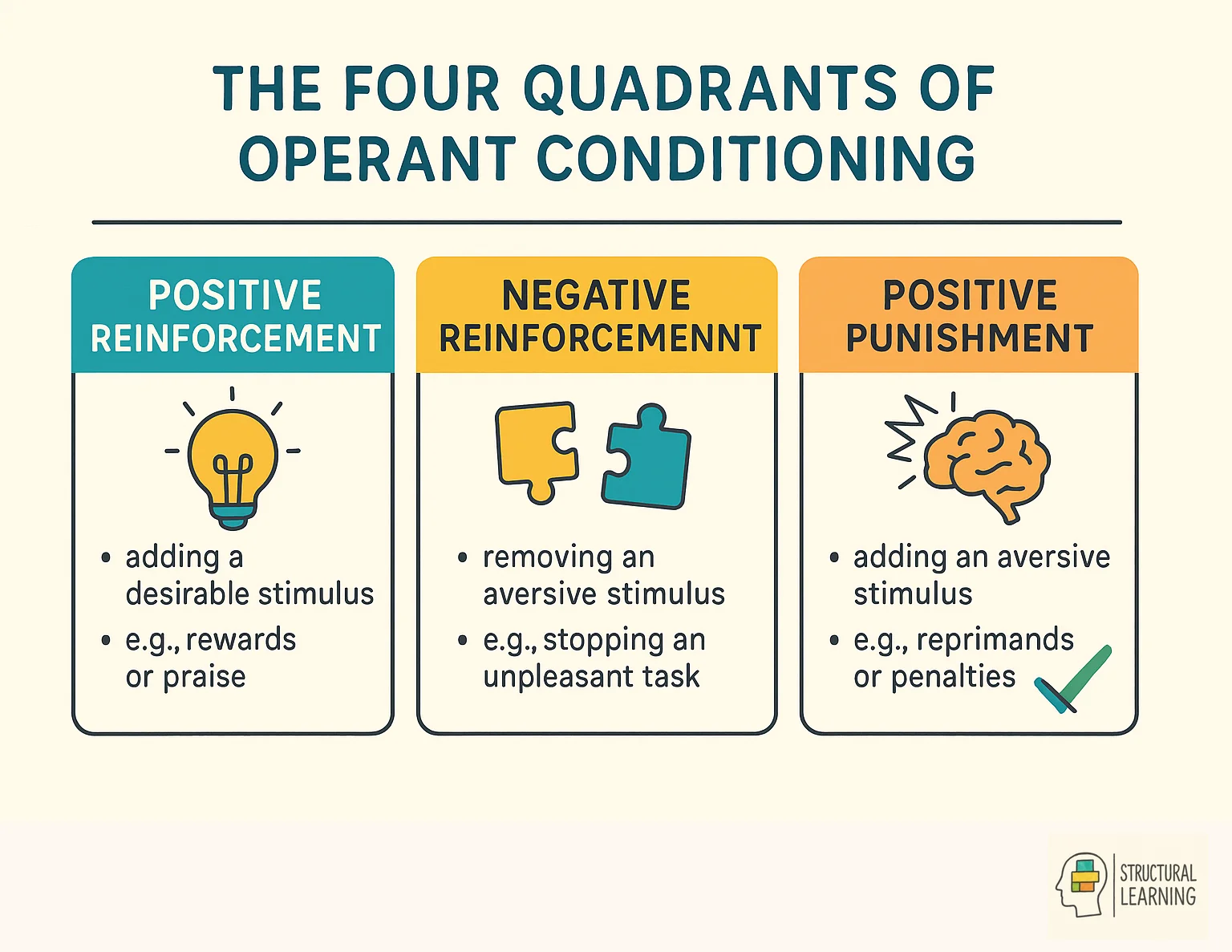

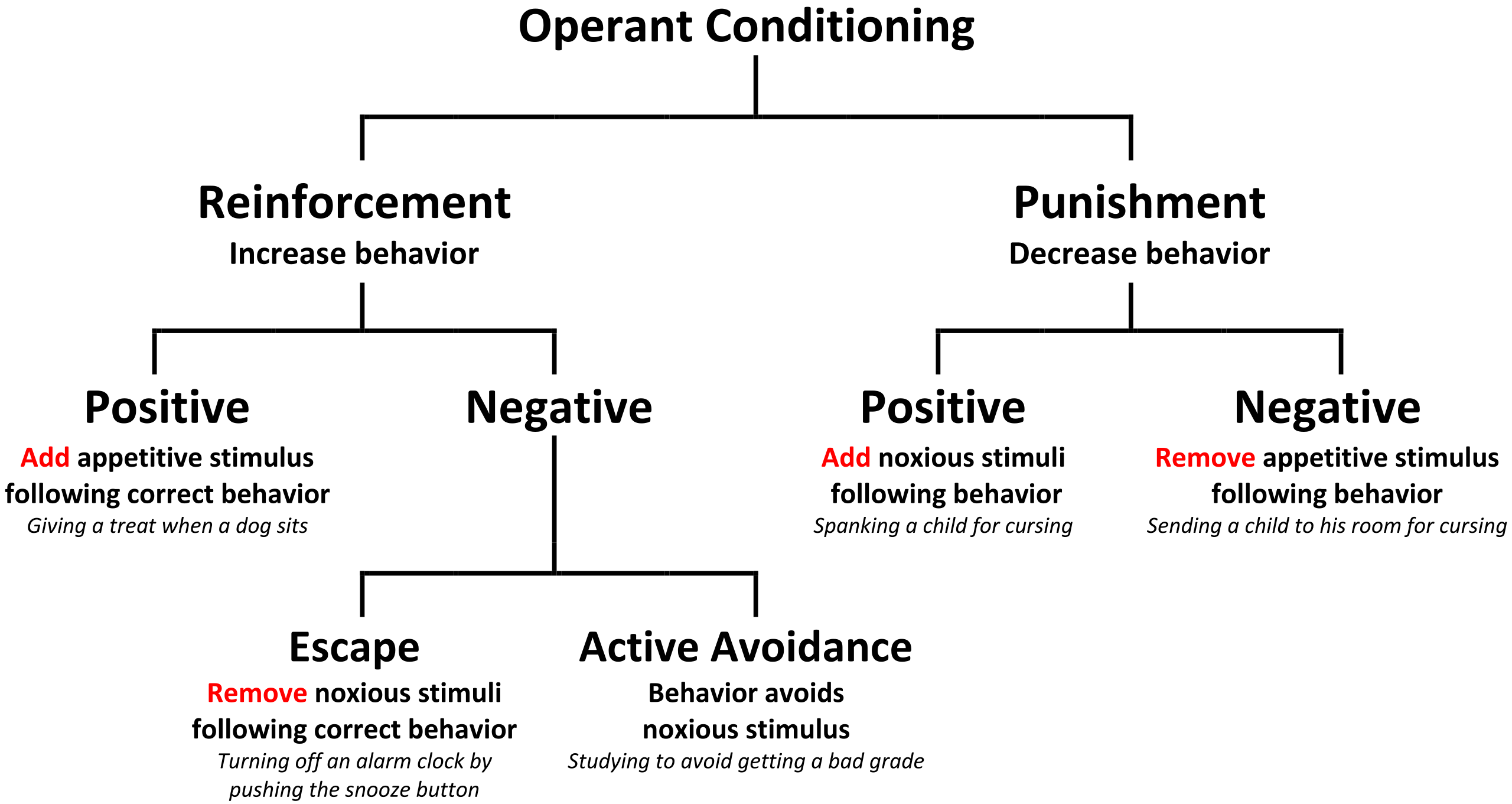

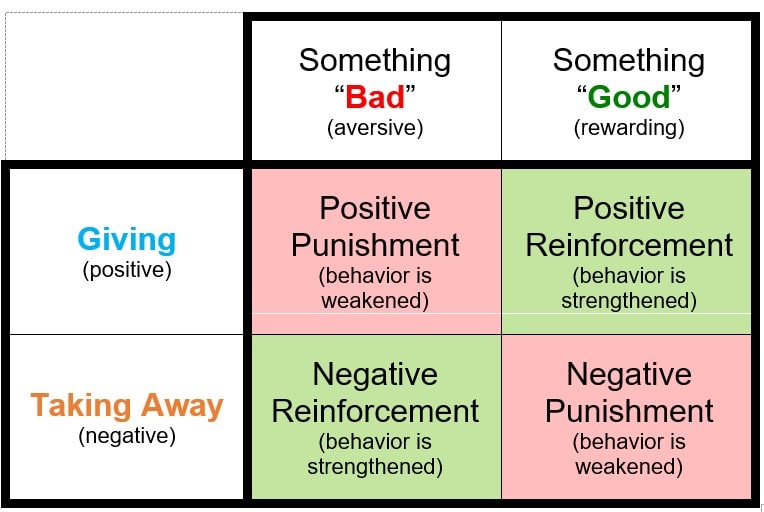

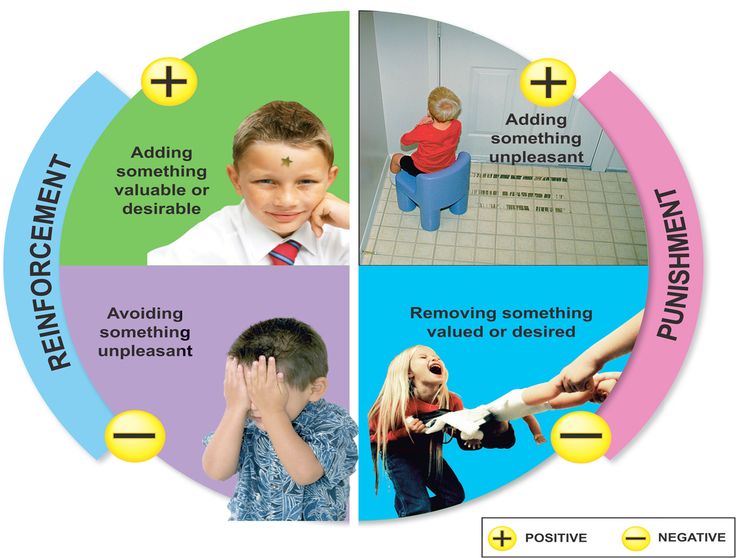

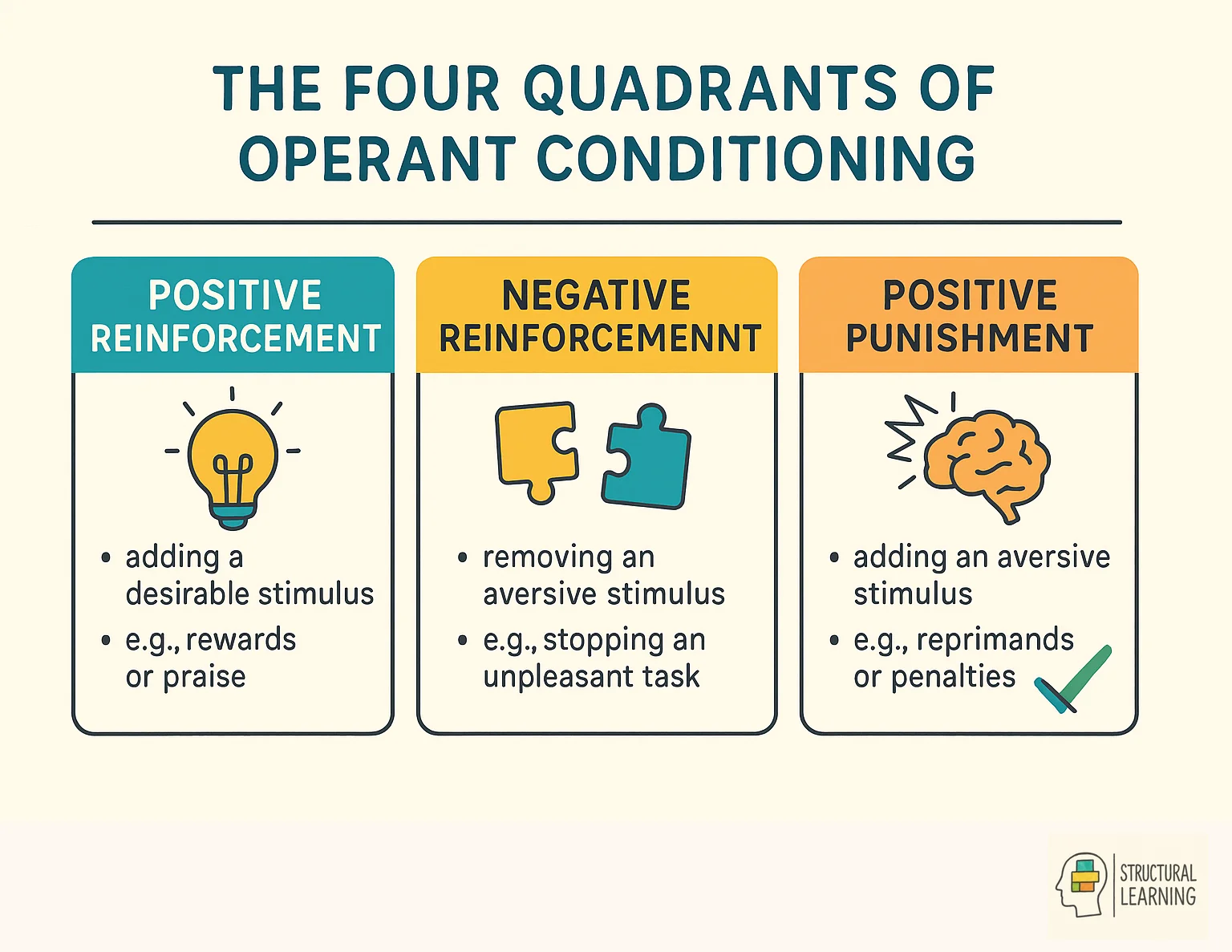

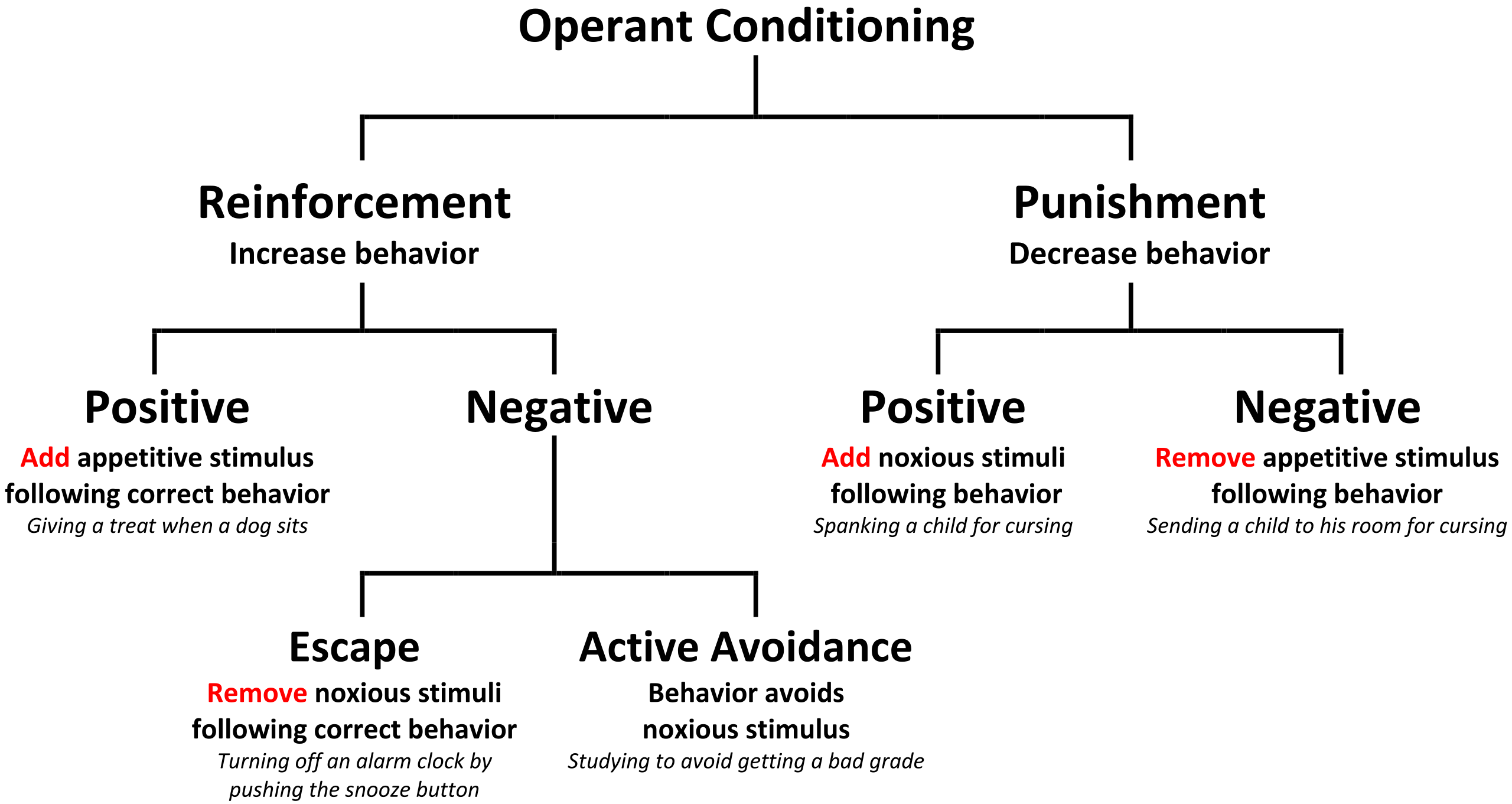

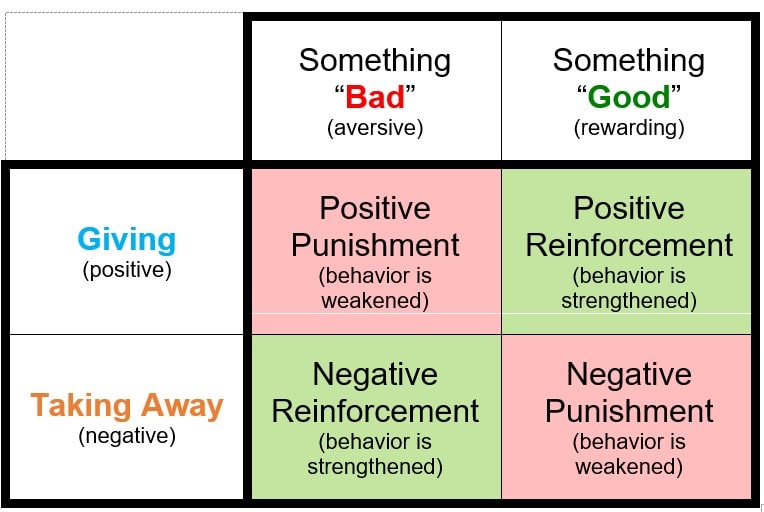

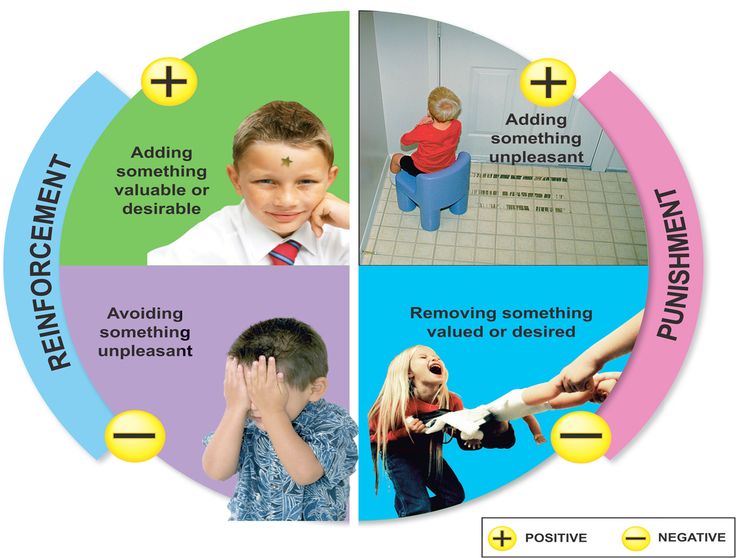

The four types are positive reinforcement (adding something pleasant), negative reinforcement (removing something unpleasant), positive punishment (adding something unpleasant), and negative punishment (removing something pleasant). Each type serves a specific purpose in either increasing or decreasing the likelihood of a behavior. These quadrants form the complete framework for understanding how consequences shape behavior.

Skinner's work, emphasising the importance of observable outcomes, distilled the principles of operant conditioning into key concepts such as reinforcement and punishment, both with positive and negative aspects.

Positive reinforcement introduces a favourable result to strengthen a behaviour, while negative reinforcement removes an unpleasant condition to achieve the same effect. In comparison, positive punishment adds an unfavourable condition to reduce a , and negative punishment removes a favourable condition to deter the behaviour.

Extinction is another principal concept within operant conditioning, occurring when a reinforced behaviour is no longer rewarded or a punished behaviour is no longer penalised, leading to a gradual reduction and disappearance of the behaviour. The process of shaping involves the strategic use of reinforcements to guide behaviours towards a desired outcome, often used in .

A critical factor in the efficacy of these principles is the timing and frequency of reinforcements. Skinner's findings show that different reinforcement schedules influence both the learning of new behaviours and the alteration of existing ones.

Classical conditioning involves automatic responses to stimuli (like salivating when hearing a bell), while operant conditioning involves voluntary behaviors modified by consequences. In classical conditioning, the response happens before the consequence, but in operant conditioning, the consequence follows the behavior. Operant conditioning focuses on choices and actions, while classical conditioning deals with reflexes and associations.

Operant conditioning differs notably from classical conditioning, another formative learning theory. While classical conditioning associates an involuntary response with a stimulus (think of with dogs and the neutral stimulus of a bell), operant conditioning is dependent on voluntary behaviours and their deliberate connection with consequences. In operant conditioning, active participation is essential, whereas classical conditioning relies on more passive responses.

In particular, the role of rewards and punishments is unique to operant conditioning. These incentives are critical for behavioural conditioning and modification, unlike classical conditioning, which doesn't employ such tactics. While classical conditioning creates associative links with natural occurrences, operant conditioning is centred on directly altering responses by either encouraging or dissuading them. Classical conditioning pairs a behaviour with a pre-existing event, whereas operant conditioning is mainly concerned with behaviours that can be influenced in a more targeted manner through reinforcements or penalties.

B.F. Skinner developed operant conditioning theory in the 1930s through his famous experiments with rats and pigeons in specially designed boxes. He demonstrated that behaviors could be systematically shaped through reinforcement schedules and consequences. His work revolutionized behavioral psychology and continues to influence education, therapy, and behavior management today.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner, a towering figure in psychology, embarked on a journey to refine and systematise operant conditioning in the mid-20th century. Beyond simply picking up where others left off, Skinner reshaped the behavioural landscape with his own narrative. Self-identifying as a radical behaviourist, he dismissed the role that inner mental states play in understanding human actions; instead, he asserted that our behaviours are solely the products of environmental factors, a belief that would become a hallmark of his approach.

In 1938, Skinner presented his seminal work, "The Behavior of Organisms," laying a robust foundation for operant conditioning. A testament to Skinner's dedication to empirical evidence, he focused his research on observable behaviour and its environmental consequences, which he believed was the only credible way to study psychology. His radical stance set him apart from colleagues, firmly rooting his theory in the physical and observable, rather than the .

B.F. Skinner not only expanded upon the concepts of operant conditioning but also harmonised them into a coherent framework that reshaped our understanding of behaviourism. He posited that behaviour is by the outcomes it produces and that we learn to behave in certain ways because of these consequences.

Skinner's influences trace back to Edward Thorndike's law of effect, yet Skinner's conceptualisations went several steps further. By situating actions within their environmental context and emphasising the reciprocal relationship between action and consequence, Skinner asserted that learned behaviours are products of operant conditioning. His principled stance toward behaviourist psychology put him at intellectual odds with traditionalists; however, his focus on observable, external factors rather than offered a revolutionary approach to understanding human and animal behaviour.

Skinner's empirical approach led to experiments primarily with animals, where he meticulously documented their learning processes. Most notably, rats and pigeons played starring roles in demonstrating operant conditioning's mechanisms. chamber, an apparatus that became synonymous with his name, which allowed for controlled studies of behavioural responses to stimuli.

Through these experiments, Skinner established a foundational understanding of how behaviour is shaped and modified by environmental changes. His exploration into reinforcements revealed the profound impact both positive and negative reinforcement could have. These findings weren't exclusive to the realm of animal behaviour; they provided invaluable insights into human psychology, particularly in educational and therapeutic contexts.

Skinner's legacy therefore not only opened a window into animal learning but also into the nuanced shaping of human behaviours, which has informed countless strategies for behaviour modification in diverse settings.

Positive reinforcement involves adding a desirable stimulus after a behavior to increase its occurrence, such as giving praise for completing homework. Effective use requires immediate delivery after the desired behavior and consistency in application. Examples include verbal praise, stickers, extra privileges, or any reward that motivates the individual.

Positive reinforcement stands as a cornerstone of operant conditioning, with profound implications for understanding and shaping human behaviour. Central to this concept is the strategy of rewarding a behaviour to increase its occurrence. By providing a desirable outcome following a specific action, positive reinforcement strengthens the connection between the behaviour and its positive consequence, encouraging repetition of the behaviour.

Whether it's through primary reinforcers, which satisfy basic needs like hunger or thirst, or secondary reinforcers, such as praise or money that have learned value, the impact on behaviour is significant. This operant conditioning tool is particularly effective in teaching new skills, fostering positive behaviours, and maintaining established behavioural patterns.

In the realm of operant conditioning, positive reinforcement involves the presentation of a reinforcing stimulus after the desired behaviour has occurred, resulting in an increased likelihood of that behaviour being repeated. Skinner demonstrated through empirical research that when a reward follows a behaviour, that behaviour is strengthened.

For instance, if a student receives verbal praise for diligently completing an assignment (the reinforcing stimulus), the student's adherence to timely work submission (the behaviour) is likely to increase. Similarly, if a dog receives a treat after sitting on command, the probability of the dog sitting in future instances when asked is strengthened. Both primary reinforcers, direct and immediate like a food treat for the dog, and secondary reinforcers, such as the praise the student receives which is a socially learned reinforcement, constitute effective examples of positive reinforcement.

The application of positive reinforcement in shaping behaviour is widely acknowledged for its ability to effectively encourage desirable actions. It's a particularly powerful method for influencing behaviour because it's based on the principle of reward rather than punishment. An individual who experiences a positive outcome from their actions is more likely to continue those actions.

For example, employees who receive bonuses for high performance are likely to maintain or improve their productivity. This method is extensively used by educators, therapists, and managers to facilitate positive behavioural changes.

However, the limitations of positive reinforcement should also be acknowledged. There can be issues with dependency, where the subject might only perform the desired behaviour when a reward is guaranteed. Additionally, if the timing and relevance of the rewards aren't carefully considered, positive reinforcement can fail to motivate or even unintentionally encourage the wrong behaviour. Thus, while powerful, positive reinforcement requires strategic application and a clear understanding of the behaviours one intends to encourage.

Implementing positive reinforcement effectively is critical to ensuring that the desired behaviour is repeated. When leveraging this tool, one should aim to immediately follow the target behaviour with a reinforcement that's meaningful to the individual. Presenting a positive reinforcement too long after the behaviour has occurred can lessen its impact and may even confuse the subject as to which behaviour is being rewarded.

In applying strategies for positive reinforcement, one should consider the following steps:

For instance, when training a pet, providing a treat right after the desired action will help the pet make the association between the action and the reward. In a classroom setting, a teacher might use a sticker chart where students receive a sticker immediately after exhibiting positive classroom behaviour, reinforcing the connection between the action and the reward.

By integrating primary or secondary reinforcers in a consistent and timely manner, individuals and organisations can effectively utilise positive reinforcement to nurture and maintain constructive behaviours, thus harnessing the power of operant conditioning for meaningful behaviour modification.

Negative reinforcement strengthens behavior by removing an unpleasant stimulus when the desired behavior occurs, like turning off an annoying alarm when you wake up. This is different from punishment because it increases rather than decreases behavior frequency. Common examples include taking pain medication to relieve discomfort or fastening a seatbelt to stop the warning beep.

Negative reinforcement is an integral concept in operant conditioning, originally described by B.F. Skinner. It occurs when a response or behaviour is strengthened by stopping, removing, or avoiding a negative outcome or aversive stimulus. Unlike positive reinforcement, which adds a pleasant stimulus to the environment to encourage a behaviour, negative reinforcement takes an unpleasant factor away, thereby increasing the likelihood that the associated behaviour will happen again in the future.

For example, imagine a scenario where an individual experiences a loud beeping noise every time they forget to buckle their seatbelt. Once they fasten the seatbelt, the annoying beep ceases. The removal of the unpleasant sound acts as a negative reinforcer, making it more likely that the individual will engage in the behaviour of buckling the seatbelt to avoid the irritation.

B.F. Skinner illustrated negative reinforcement using an electric current in experiments with rats. When a rat was placed in a Skinner box (an operant conditioning chamber), it was subjected to a mild electric current, which caused discomfort. To escape this discomfort, the rat would have to perform a specific behaviour, such as knocking a lever. As soon as the lever was hit, the electric current would stop. This setup effectively taught the rat to perform the desired behaviour to avoid the unpleasant stimulus.

Negative reinforcement in operant conditioning involves the elimination or reduction of an unpleasant stimulus, thereby reinforcing the behaviour that preceded the removal. This principle is key to understanding how behaviours can become more frequent without resorting to rewards.

Take an academic context as an example: students may find homework to be a stressful aspect of their school routine. If a teacher notices greater class participation and decides to alleviate the workload by cancelling homework for the day, students are likely to associate active participation with the relief of not having homework. Henceforth, the students' participation in class discussions is likely to increase as they seek to avoid the unwelcome task.

In the context of operant conditioning, it's important to differentiate between negative reinforcement and positive punishment, as they serve opposite functions in terms of behaviour modification. Negative reinforcement increases a behaviour's occurrence by removing a negative condition, while positive punishment decreases a behaviour by adding an undesirable consequence.

To illustrate, when a student is texting during class, a teacher might employ positive punishment by scolding the student. The addition of the reprimand is intended to reduce the likelihood of the student texting in the future. Conversely, negative punishment involves removing a positive stimulus to decrease an unwanted behaviour. For example, a parent might take away a child's video game privileges because they didn't do their chores. The removal of the enjoyable activity is meant to discourage the neglect of responsibilities.

Reinforcement, whether negative or positive, always aims at increasing the frequency of a behaviour. On the other hand, punishment, whether positive or negative, seeks to decrease a behaviour. When considering these strategies, it's also worth mentioning the concept of extinction in operant conditioning. Extinction transpires when a behaviour that has previously been reinforced is no longer followed by reinforcement, which consequently leads to a gradual reduction in the behaviour's occurrence.

Positive punishment involves adding an unpleasant consequence after an unwanted behavior to reduce its occurrence, such as assigning extra chores for breaking rules. While it can be effective for immediate behavior change, it may have negative side effects like increased aggression or avoidance. It's most appropriate for serious safety violations or when other methods have failed.

Operant conditioning, a key behavioural principle established by B.F. Skinner, frequently utilises positive punishment as a technique to decrease undesirable behaviours. Positive punishment involves the addition of an aversive or unpleasant stimulus immediately following a behaviour with the intention of reducing the likelihood of that behaviour's recurrence.

Unlike negative reinforcement, which seeks to increase a behaviour by removing a negative condition, positive punishment aims to weaken or suppress a behaviour by introducing an adverse consequence.

The concept of positive punishment can be succinctly defined within the framework of operant conditioning as the process of adding an undesirable stimulus to decrease the frequency of a behaviour. This form of punishment functions by creating a negative association with the behaviour that's to be modified.

An everyday example is when a parent disciplines a child for misbehaviour. If a child runs into the street without looking and is immediately scolded, the scolding is the added aversive stimulus intended to reduce the likelihood of the child engaging in that unsafe behaviour again.

Another illustration is within the classroom environment. If a student is frequently interrupting class by talking to their peers, the teacher might assign extra homework each time the student disrupts the class. The introduction of more work is the positive punishment intended to discourage interruptions.

While positive punishment can be an effective method for decreasing unwanted behaviours, it also raises several ethical considerations. It's essential for those implementing such behavioural interventions, like educators, therapists, and parents, to weigh the potential implications of using positive punishment:

Professionals and caregivers are advised to consider positive reinforcement techniques and other behaviour modification strategies that encourage desirable behaviours through rewards rather than utilising punishment. Ethical application, if punishment is used, requires it to be proportionate, consistent, and paired with clear communication so that the individual understands which behaviour is being targeted and why.

Positive punishment is a component of the principles of operant conditioning, effective for decreasing unwanted behaviours. However, its use must be approached with caution, considering the ethical implications and potential psychological impacts, privileging positive reinforcement strategies whenever possible for a more constructive approach to behaviour modification.

Negative punishment reduces unwanted behavior by removing something pleasant, such as taking away screen time for misbehavior. This technique works best when the removed item is genuinely valued by the individual and the connection to the behavior is clear. It tends to be less emotionally charged than positive punishment and can be effective for reducing attention-seeking behaviors.

Operant conditioning encompasses various techniques intended to influence behaviour, among which negative punishment plays a significant role. This method involves the removal of a desirable stimulus or something rewarding immediately following a behaviour with the intention to decrease the likelihood of the behaviour's recurrence. Unlike positive punishment, which involves adding an aversive stimulus, negative punishment reduces behaviour by taking away something valued by the individual. This approach is often used in various settings, from homes to schools, to manage undesirable behaviours effectively.

Common examples include losing driving privileges for breaking curfew, having recess time reduced for not completing work, or removing a favorite toy after aggressive behavior. Time-outs are a classic form where attention and stimulation are removed following misbehavior. These consequences work by making the individual realize that undesirable behaviors lead to the loss of things they enjoy.

Negative punishment is characterised by the removal of a positive stimulus in response to an undesired behaviour with the aim of diminishing the behaviour. For instance, consider a teenager who enjoys playing video games daily. If the teenager fails to complete their chores, their parent might retract their gaming privileges. This withdrawal acts as negative punishment because the removal of a valued pleasure, the opportunity to play video games, is intended to encourage the completion of chores in the future.

Another example is seen in the workplace, where an employee who habitually arrives late might lose the privilege of flexible work hours. The loss of flexibility serves as negative punishment, setting the expectation that punctuality will lead to the reinstatement of the flexible schedule.

Effective alternatives include positive reinforcement for desired behaviors, natural consequences, and teaching replacement behaviors through modeling. Restorative practices that focus on repairing harm and building empathy can address underlying issues better than removal of privileges. Proactive strategies like clear expectations, engaging instruction, and relationship building prevent many behavior problems before they start.

While negative punishment is a tool for reducing undesirable behaviour, it isn't the only method available within operant conditioning. Alternatives to negative punishment can often yield more sustainable behaviour change. Edwin Guthrie proposed altering behaviour patterns by gradually intensifying a weak stimulus. Rather than simply removing a reward or pleasure, this method aims to shift behaviour steadily and gently.

Furthermore, the exclusive use of punishment can fail to teach the preferred, positive behaviour; it may instead only suppress the unwanted behaviour temporarily. That's why operant conditioning also emphasises positive reinforcement, rewarding good behaviour to encourage its repetition.

Instead of solely depending on negative consequences, behaviour modification techniques often incorporate positive reinforcement strategies. For example, implementing a rewards system contingent upon the demonstration of positive behaviours can be more motivating and less detrimental than punishment. The promise of additional privileges or tangible rewards can incentivise individuals to modify their behaviour.

In behaviour modification, a balance of positive reinforcement (introducing a positive outcome) and negative reinforcement (removing an aversive outcome) should be considered, in addition to punishment tactics. This balance ensures a comprehensive approach to shaping behaviour not just through the avoidance of negative outcomes, but also through the pursuit of positive ones.

Reinforcement builds positive associations with desired behaviors and maintains better relationships between teachers and students. Research shows reinforced behaviors are more likely to generalize to other settings and persist over time compared to punished behaviors. Reinforcement also promotes intrinsic motivation and self-esteem while punishment can create fear, resentment, and avoidance of learning situations.

Within this framework lies the concept of reinforcement, a process that increases the likelihood of a behaviour recurring. Reinforcements can be positive or negative, with each serving a unique purpose in behaviour modification.

Positive reinforcement involves the introduction of a favourable event or outcome after a desired behaviour, thereby reinforcing that behaviour. The adding of something enjoyable or rewarding encourages repetition of the behaviour. On the other hand, negative reinforcement occurs when an unfavourable event or outcome is removed following a good behaviour. The removal of something aversive consequently strengthens the likelihood of the behaviour being repeated.

In both types of reinforcement, behaviours are encouraged and strengthened. Moreover, these reinforcements can be broken down into primary and secondary categories, and they can be delivered according to different reinforcement schedules to effectively shape and maintain behaviours. Notably, operant conditioning isn't just a theoretical construct; it's applied practically in diverse fields, including education, parenting, workplace management, relationship development, and therapeutic interventions for behavioural issues.

Primary Reinforcers play a direct and innate role in encouraging behaviours by satisfying biological needs, without needing to be learned. Secondary Reinforcers are associated with primary ones and acquire their value through this connection, often dependent on the individual's experiences or culture. Also, operant conditioning includes reinforcement strategies like token economies, which utilise secondary reinforcers to motivate and sustain behaviours through a system of exchange for primary rewards.

Now that we have a foundational understanding, let's examine the specifics of primary and secondary reinforcers.

Primary reinforcers are innately satisfying as they fulfil basic biological needs and desires without requiring any learning process. These are the fundamental aspects of survival and comfort that are universally compelling. Food, water, sleep, and shelter are quintessential examples, as they satisfy hunger, thirst, fatigue, and the need for security, respectively. The fundamental nature of these needs ensures that primary reinforcers retain their reinforcing power naturally.

Take the pleasure principle, for instance. Engaging in activities that produce pleasure, such as eating a delicious meal or experiencing sexual gratification, reinforces the behaviour that led to that pleasure due to the immediate satisfaction it provides. Similarly, on a hot day, jumping into a cool body of water brings instant relief and enjoyment. Here, the coolness of the water acts as a primary reinforcer, as it satisfies the need to reduce body temperature and the innate desire for comfort.

These primary reinforcers are central to operant conditioning because they don't need to be paired with any other stimuli to be effective; their potency is inherent. They're the building blocks upon which more complex reinforcement systems are built, and they serve as powerful motivators for desired behaviours.

Secondary reinforcers, unlike primary ones, don't innately satisfy physical needs. Instead, they have value to an individual owing to their association with primary reinforcers. These are learned reinforcements and are highly variable from person to person, shaped by individual experiences, cultural background, and learned associations.

Praise, for example, may serve as a secondary reinforcer when it's linked to the affection or approval that fulfils a social need. Money is perhaps the most ubiquitous secondary reinforcer; it has no intrinsic value but can be used to purchase a wide array of primary reinforcers like food, water, and shelter, thereby acquiring its reinforcing power. Similarly, points or stickers are often used in educational settings as tokens, serving as secondary reinforcers with the understanding that accumulating enough of them can lead to a primary reinforcer, such as a special privilege or reward.

Secondary reinforcers also encompass generalised reinforcers, which aren't limited in scope to a single primary reward but can be used in several exchanges. Money is again the classic example, as it harnesses the ability to facilitate the acquisition of numerous primary reinforcers, be it nutritious meals, comfortable living conditions, or enjoyable experiences.

Reinforcement, whether primary or secondary, isn't applied in isolation. Using reinforcement schedules, such as fixed or variable intervals, allows for the careful and strategic delivery of reinforcement to maintain and shape behaviours. This intricate web of reinforcements and schedules forms the very fabric of operant conditioning, making it an immensely powerful tool in influencing human behaviour.

The four main schedules are fixed ratio (reinforcement after set number of responses), variable ratio (after varying number of responses), fixed interval (after set time period), and variable interval (after varying time periods). Variable schedules create more persistent behaviors that resist extinction, while fixed schedules produce predictable response patterns. Each schedule has specific advantages for different learning goals and situations.

Operant conditioning extends its influence on behaviour through the strategic use of reinforcement schedules. These schedules are critical because they define the rules that govern the timing and frequency of reinforcements, whether it's a reward or the removal of an aversive stimulus.

Organised into two main categories based on time and ratio, these schedules are known as fixed and variable intervals and fixed and variable ratios. These schedules can greatly affect the response rates and patterns of the subjects involved, providing a systematic approach to reinforcing desired behaviours.

For example, a patient in a hospital might receive pain relief medication at routine intervals, while a social media user might check their feed at irregular times. Both instances are driven by underlying reinforcement schedules that shape their behaviours.

The Fixed Interval (FI) reinforcement schedule involves reinforcements being provided after specific, predictable time intervals. Under FI, a moderate and scalloped response rate is often observed due to significant pauses after the reinforcement is delivered.

Conversely, the Variable Interval (VI) schedule doles out reinforcement after unpredictable time intervals. This schedule typically results in a moderate, steady rate of response with no predictable pauses because the next reinforcement could come at any time. On the ratio side, a Fixed Ratio (FR) schedule delivers reinforcement after a set number of responses.

This leads to a high response rate, typically followed by a pause once the reinforcement has been received. Finally, the Variable Ratio (VR) schedule is perhaps the most effective at eliciting a high and steady rate of response, as reinforcements are given after an unpredictable number of responses. This is what makes gambling so compulsive; the reinforcement (winning) is doled out on a VR schedule.

The applications of these reinforcement schedules are manifold and can profoundly impact behaviour management in various settings. For instance, with the FI schedule's predictable reinforcements, behaviours can be shaped around consistent rewards, like a salaried employee getting paid monthly.

However, considerations such as the potential for pause after the reinforcement need to be taken into account, which can affect productivity. VI schedules keep individuals engaged for longer periods as they can't predict when the next reinforcement will occur, as seen in behaviours like repeatedly checking for emails or likes on social media.

FR schedules are instrumental in environments like manufacturing where piece-rate pay can motivate a flurry of activity. However, the post-reinforcement pauses can lead to a drop in productivity. Lastly, the VR schedule is exceptionally effective in maintaining high rates of engagement and preventing predictability-based drop-offs in response. This is witnessed in places like casinos, where slot machines operate on this principle. In behaviour modification, this might be used to promote consistent engagement with learning materials or therapies.

Understanding these schedules not only allows psychologists and behaviourists to predict and shape behaviours but also offers valuable insights for educators, employers, and even parents. By harnessing the power of these reinforcement schedules, desired behaviours can be cultivated and maintained effectively, leading to potentially positive outcomes in both human and animal subjects.

Start by identifying specific target behaviors and collecting baseline data on their frequency. Design a reinforcement system that rewards desired behaviors immediately and consistently, using tokens, points, or privileges that students value. Monitor progress through data collection and adjust the intervention based on results, gradually fading external reinforcements as behaviors become habitual.

Behaviour modification employs operant conditioning, a powerful method for altering human behaviour. At its core, operant conditioning utilises principles such as reinforcement and punishment to encourage desirable behaviours and diminish unwanted ones. In practice, behaviour modification techniques often incorporate token economies, using items like sticker charts as a form of positive reinforcement.

Positive reinforcement, such as praise and rewards, is fundamental in strengthening desired behaviours. On the other hand, ignoring or applying punishment can help reduce or eliminate undesired behaviours. For instance, parents often use operant conditioning by offering verbal praise for good manners or instituting a reward system for chores to foster positive behaviours in their children.

Operant conditioning not only thrives in home settings but also extends to schools, where teachers may reward high academic performance with recognition or special privileges, and in workplaces, where incentives are offered for increased productivity. Even within relationships, positive reinforcement through compliments or gifts can reinforce loving or helpful actions.

| Operant Conditioning Technique |

Application Example |

|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement |

Praise for completing homework |

| Negative Reinforcement |

Removing chores for good behaviour |

| Positive Punishment |

Extra tasks for rule violations |

| Negative Punishment |

Loss of privileges for misconduct |

Essential readings include Skinner's 'Science and Human Behavior' and 'About Behaviorism' for foundational theory. Modern applications are covered in Cooper, Heron, and Heward's 'Applied Behavior Analysis' textbook. For practical classroom strategies, consult Alberto and Troutman's 'Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers' or online courses from behavior analysis certification boards.

Operant conditioning has been applied extensively to various settings and populations, demonstrating its efficacy in modifying behaviour. The following five key studies highlight the effectiveness of operant conditioning across different contexts, including mental health, childhood behaviour, vocal accuracy, schizophrenia, and pain management.

These studies collectively demonstrate that operant conditioning is an effective technique across diverse settings, from mental health treatment to improving specific behaviours like vocal accuracy and managing chronic pain. The principles of operant conditioning, such as the use of positive reinforcers and behavioural responses to stimuli, are consistently shown to produce beneficial outcomes over varying periods of time.

Operant conditioning is a learning process where behaviours are modified through consequences like rewards or punishments, making actions more or less likely to be repeated. As an evidence-based approach to classroom management, these principles remain highly relevant for modern educators seeking effective strategies to shape student behaviour and enhance learning environments.

Teachers can use positive reinforcement by adding praise or rewards for good behaviour, negative reinforcement by removing unpleasant tasks when students comply, positive punishment by adding consequences for misbehaviour, and negative punishment by removing privileges. Each type serves a specific purpose in either encouraging desired behaviours or discouraging unwanted ones.

Classical conditioning involves automatic responses to stimuli, while operant conditioning focuses on voluntary behaviours modified by consequences that follow the action. Operant conditioning is generally more useful for classroom management because it deals with deliberate choices and actions that teachers can directly influence through targeted reinforcements or penalties.

The timing and frequency of reinforcement significantly affects how quickly behaviours are learned and how resistant they are to extinction. Different reinforcement schedules influence both the acquisition of new behaviours and the modification of existing ones, making strategic timing crucial for effective classroom management.

Primary reinforcers include basic needs like snacks or drinks, secondary reinforcers involve social rewards like verbal praise or recognition, and generalised reinforcers include token systems or points that can be exchanged for privileges. Understanding these different types helps teachers choose appropriate motivators for various students and situations.

Educators can focus more on reinforcement strategies, using positive reinforcement to encourage desired behaviours and negative reinforcement to remove unpleasant conditions when students comply. When correction is needed, negative punishment (removing privileges) is often more effective than positive punishment (adding unpleasant consequences) for maintaining positive classroom relationships.

Behavioural shaping involves the strategic use of reinforcements to gradually guide behaviours towards a desired outcome by rewarding successive approximations of the target behaviour. Teachers can use this technique to help struggling students by breaking complex skills or behaviours into smaller steps and reinforcing progress at each stage.

Tracing its origins back to the early 20th century, operant conditioning is a fundamental concept within behavioral psychology, providing a framework for understanding how our actions are shaped by their consequences. As you're about to explore the intricacies of operant conditioning, it's like unlocking a door to the understanding of behaviour. In 2025, these principles remain as relevant as ever for educators seeking evidence-based approaches to classroom management.

laid the cornerstone for a systematic approach to studying behavior, making him one of the most influential psychologists of his time. His theories continue to resonate in psychology and education, inviting both accolades and debate. The article ahead explores Skinner's contributions and the experiments that transformed our understanding of behaviour.

Reward or consequence? This dilemma plays a central role in operant conditioning through concepts such as reinforcement and punishment. Whether enhancing learning environments or modifying behaviour, the application of these principles is vast and nuanced. With positive and negative reinforcements and punishments shaping complex behaviours, you're poised to explore strategies for influence and change. Prepare to examine the mechanisms of behaviour modification in the sprawling landscape of reinforcement theory.

Operant conditioning is a learning process where behaviors are modified through consequences like rewards or punishments. When a behavior is followed by a positive outcome, it's more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by negative outcomes tend to decrease. This principle explains how we learn from the results of our actions in everyday life.

Operant conditioning is a fundamental theory in , originally established by notable psychologist B.F. Skinner during the 1930s. This theory proposes a connection between behaviours and their subsequent consequences, which are categorised as either reinforcers or punishers. Reinforcers are outcomes that increase the likelihood of a behaviour recurring, while punishers decrease its occurrence. This dynamic is central to the process of learning and behaviour modification.

Behaviour, in the context of operant conditioning, is influenced by the reinforcement schedules used. These schedules determine the timing and regularity of reinforcements, shaping both simple and complex behaviours over time.

Skinner's focus on observable and measurable responses led him to devise experiments, particularly with animals, that demonstrated the power of environmental changes to alter behaviours. Using tools like the operant conditioning chamber, Skinner was able to carefully control the stimuli and consequent responses, thereby providing strong support for his theory.

At its core, operant conditioning involves a stimulus that elicits a voluntary behaviour, which is then followed by a consequence. Reinforcers used to shape behaviour can be primary, such as food or drink, secondary, like verbal praise, or generalised, involving like money.

Operant conditioning works by creating associations between voluntary behaviors and their consequences. When a behavior leads to a desirable outcome (reinforcement), the behavior becomes stronger and more frequent. Conversely, when a behavior leads to an undesirable outcome (punishment), it becomes weaker and less frequent.

Operant conditioning explores reversible behaviour that's "controlled" by consequences. At the heart of this learning model lies the principle that behaviours which are reinforced tend to be repeated, increasing the probability of those behaviours being exhibited in the future. Conversely, behaviours that are met with punishment are less likely to reoccur.

Operant conditioning emphasises the relationship between behaviours and their resulting effects, whether behaviours are encouraged with positive outcomes or discouraged by undesirable results.

The four types are positive reinforcement (adding something pleasant), negative reinforcement (removing something unpleasant), positive punishment (adding something unpleasant), and negative punishment (removing something pleasant). Each type serves a specific purpose in either increasing or decreasing the likelihood of a behavior. These quadrants form the complete framework for understanding how consequences shape behavior.

Skinner's work, emphasising the importance of observable outcomes, distilled the principles of operant conditioning into key concepts such as reinforcement and punishment, both with positive and negative aspects.

Positive reinforcement introduces a favourable result to strengthen a behaviour, while negative reinforcement removes an unpleasant condition to achieve the same effect. In comparison, positive punishment adds an unfavourable condition to reduce a , and negative punishment removes a favourable condition to deter the behaviour.

Extinction is another principal concept within operant conditioning, occurring when a reinforced behaviour is no longer rewarded or a punished behaviour is no longer penalised, leading to a gradual reduction and disappearance of the behaviour. The process of shaping involves the strategic use of reinforcements to guide behaviours towards a desired outcome, often used in .

A critical factor in the efficacy of these principles is the timing and frequency of reinforcements. Skinner's findings show that different reinforcement schedules influence both the learning of new behaviours and the alteration of existing ones.

Classical conditioning involves automatic responses to stimuli (like salivating when hearing a bell), while operant conditioning involves voluntary behaviors modified by consequences. In classical conditioning, the response happens before the consequence, but in operant conditioning, the consequence follows the behavior. Operant conditioning focuses on choices and actions, while classical conditioning deals with reflexes and associations.

Operant conditioning differs notably from classical conditioning, another formative learning theory. While classical conditioning associates an involuntary response with a stimulus (think of with dogs and the neutral stimulus of a bell), operant conditioning is dependent on voluntary behaviours and their deliberate connection with consequences. In operant conditioning, active participation is essential, whereas classical conditioning relies on more passive responses.

In particular, the role of rewards and punishments is unique to operant conditioning. These incentives are critical for behavioural conditioning and modification, unlike classical conditioning, which doesn't employ such tactics. While classical conditioning creates associative links with natural occurrences, operant conditioning is centred on directly altering responses by either encouraging or dissuading them. Classical conditioning pairs a behaviour with a pre-existing event, whereas operant conditioning is mainly concerned with behaviours that can be influenced in a more targeted manner through reinforcements or penalties.

B.F. Skinner developed operant conditioning theory in the 1930s through his famous experiments with rats and pigeons in specially designed boxes. He demonstrated that behaviors could be systematically shaped through reinforcement schedules and consequences. His work revolutionized behavioral psychology and continues to influence education, therapy, and behavior management today.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner, a towering figure in psychology, embarked on a journey to refine and systematise operant conditioning in the mid-20th century. Beyond simply picking up where others left off, Skinner reshaped the behavioural landscape with his own narrative. Self-identifying as a radical behaviourist, he dismissed the role that inner mental states play in understanding human actions; instead, he asserted that our behaviours are solely the products of environmental factors, a belief that would become a hallmark of his approach.

In 1938, Skinner presented his seminal work, "The Behavior of Organisms," laying a robust foundation for operant conditioning. A testament to Skinner's dedication to empirical evidence, he focused his research on observable behaviour and its environmental consequences, which he believed was the only credible way to study psychology. His radical stance set him apart from colleagues, firmly rooting his theory in the physical and observable, rather than the .

B.F. Skinner not only expanded upon the concepts of operant conditioning but also harmonised them into a coherent framework that reshaped our understanding of behaviourism. He posited that behaviour is by the outcomes it produces and that we learn to behave in certain ways because of these consequences.

Skinner's influences trace back to Edward Thorndike's law of effect, yet Skinner's conceptualisations went several steps further. By situating actions within their environmental context and emphasising the reciprocal relationship between action and consequence, Skinner asserted that learned behaviours are products of operant conditioning. His principled stance toward behaviourist psychology put him at intellectual odds with traditionalists; however, his focus on observable, external factors rather than offered a revolutionary approach to understanding human and animal behaviour.

Skinner's empirical approach led to experiments primarily with animals, where he meticulously documented their learning processes. Most notably, rats and pigeons played starring roles in demonstrating operant conditioning's mechanisms. chamber, an apparatus that became synonymous with his name, which allowed for controlled studies of behavioural responses to stimuli.

Through these experiments, Skinner established a foundational understanding of how behaviour is shaped and modified by environmental changes. His exploration into reinforcements revealed the profound impact both positive and negative reinforcement could have. These findings weren't exclusive to the realm of animal behaviour; they provided invaluable insights into human psychology, particularly in educational and therapeutic contexts.

Skinner's legacy therefore not only opened a window into animal learning but also into the nuanced shaping of human behaviours, which has informed countless strategies for behaviour modification in diverse settings.

Positive reinforcement involves adding a desirable stimulus after a behavior to increase its occurrence, such as giving praise for completing homework. Effective use requires immediate delivery after the desired behavior and consistency in application. Examples include verbal praise, stickers, extra privileges, or any reward that motivates the individual.

Positive reinforcement stands as a cornerstone of operant conditioning, with profound implications for understanding and shaping human behaviour. Central to this concept is the strategy of rewarding a behaviour to increase its occurrence. By providing a desirable outcome following a specific action, positive reinforcement strengthens the connection between the behaviour and its positive consequence, encouraging repetition of the behaviour.

Whether it's through primary reinforcers, which satisfy basic needs like hunger or thirst, or secondary reinforcers, such as praise or money that have learned value, the impact on behaviour is significant. This operant conditioning tool is particularly effective in teaching new skills, fostering positive behaviours, and maintaining established behavioural patterns.

In the realm of operant conditioning, positive reinforcement involves the presentation of a reinforcing stimulus after the desired behaviour has occurred, resulting in an increased likelihood of that behaviour being repeated. Skinner demonstrated through empirical research that when a reward follows a behaviour, that behaviour is strengthened.

For instance, if a student receives verbal praise for diligently completing an assignment (the reinforcing stimulus), the student's adherence to timely work submission (the behaviour) is likely to increase. Similarly, if a dog receives a treat after sitting on command, the probability of the dog sitting in future instances when asked is strengthened. Both primary reinforcers, direct and immediate like a food treat for the dog, and secondary reinforcers, such as the praise the student receives which is a socially learned reinforcement, constitute effective examples of positive reinforcement.

The application of positive reinforcement in shaping behaviour is widely acknowledged for its ability to effectively encourage desirable actions. It's a particularly powerful method for influencing behaviour because it's based on the principle of reward rather than punishment. An individual who experiences a positive outcome from their actions is more likely to continue those actions.

For example, employees who receive bonuses for high performance are likely to maintain or improve their productivity. This method is extensively used by educators, therapists, and managers to facilitate positive behavioural changes.

However, the limitations of positive reinforcement should also be acknowledged. There can be issues with dependency, where the subject might only perform the desired behaviour when a reward is guaranteed. Additionally, if the timing and relevance of the rewards aren't carefully considered, positive reinforcement can fail to motivate or even unintentionally encourage the wrong behaviour. Thus, while powerful, positive reinforcement requires strategic application and a clear understanding of the behaviours one intends to encourage.

Implementing positive reinforcement effectively is critical to ensuring that the desired behaviour is repeated. When leveraging this tool, one should aim to immediately follow the target behaviour with a reinforcement that's meaningful to the individual. Presenting a positive reinforcement too long after the behaviour has occurred can lessen its impact and may even confuse the subject as to which behaviour is being rewarded.

In applying strategies for positive reinforcement, one should consider the following steps:

For instance, when training a pet, providing a treat right after the desired action will help the pet make the association between the action and the reward. In a classroom setting, a teacher might use a sticker chart where students receive a sticker immediately after exhibiting positive classroom behaviour, reinforcing the connection between the action and the reward.

By integrating primary or secondary reinforcers in a consistent and timely manner, individuals and organisations can effectively utilise positive reinforcement to nurture and maintain constructive behaviours, thus harnessing the power of operant conditioning for meaningful behaviour modification.

Negative reinforcement strengthens behavior by removing an unpleasant stimulus when the desired behavior occurs, like turning off an annoying alarm when you wake up. This is different from punishment because it increases rather than decreases behavior frequency. Common examples include taking pain medication to relieve discomfort or fastening a seatbelt to stop the warning beep.

Negative reinforcement is an integral concept in operant conditioning, originally described by B.F. Skinner. It occurs when a response or behaviour is strengthened by stopping, removing, or avoiding a negative outcome or aversive stimulus. Unlike positive reinforcement, which adds a pleasant stimulus to the environment to encourage a behaviour, negative reinforcement takes an unpleasant factor away, thereby increasing the likelihood that the associated behaviour will happen again in the future.

For example, imagine a scenario where an individual experiences a loud beeping noise every time they forget to buckle their seatbelt. Once they fasten the seatbelt, the annoying beep ceases. The removal of the unpleasant sound acts as a negative reinforcer, making it more likely that the individual will engage in the behaviour of buckling the seatbelt to avoid the irritation.

B.F. Skinner illustrated negative reinforcement using an electric current in experiments with rats. When a rat was placed in a Skinner box (an operant conditioning chamber), it was subjected to a mild electric current, which caused discomfort. To escape this discomfort, the rat would have to perform a specific behaviour, such as knocking a lever. As soon as the lever was hit, the electric current would stop. This setup effectively taught the rat to perform the desired behaviour to avoid the unpleasant stimulus.

Negative reinforcement in operant conditioning involves the elimination or reduction of an unpleasant stimulus, thereby reinforcing the behaviour that preceded the removal. This principle is key to understanding how behaviours can become more frequent without resorting to rewards.

Take an academic context as an example: students may find homework to be a stressful aspect of their school routine. If a teacher notices greater class participation and decides to alleviate the workload by cancelling homework for the day, students are likely to associate active participation with the relief of not having homework. Henceforth, the students' participation in class discussions is likely to increase as they seek to avoid the unwelcome task.

In the context of operant conditioning, it's important to differentiate between negative reinforcement and positive punishment, as they serve opposite functions in terms of behaviour modification. Negative reinforcement increases a behaviour's occurrence by removing a negative condition, while positive punishment decreases a behaviour by adding an undesirable consequence.

To illustrate, when a student is texting during class, a teacher might employ positive punishment by scolding the student. The addition of the reprimand is intended to reduce the likelihood of the student texting in the future. Conversely, negative punishment involves removing a positive stimulus to decrease an unwanted behaviour. For example, a parent might take away a child's video game privileges because they didn't do their chores. The removal of the enjoyable activity is meant to discourage the neglect of responsibilities.

Reinforcement, whether negative or positive, always aims at increasing the frequency of a behaviour. On the other hand, punishment, whether positive or negative, seeks to decrease a behaviour. When considering these strategies, it's also worth mentioning the concept of extinction in operant conditioning. Extinction transpires when a behaviour that has previously been reinforced is no longer followed by reinforcement, which consequently leads to a gradual reduction in the behaviour's occurrence.

Positive punishment involves adding an unpleasant consequence after an unwanted behavior to reduce its occurrence, such as assigning extra chores for breaking rules. While it can be effective for immediate behavior change, it may have negative side effects like increased aggression or avoidance. It's most appropriate for serious safety violations or when other methods have failed.

Operant conditioning, a key behavioural principle established by B.F. Skinner, frequently utilises positive punishment as a technique to decrease undesirable behaviours. Positive punishment involves the addition of an aversive or unpleasant stimulus immediately following a behaviour with the intention of reducing the likelihood of that behaviour's recurrence.

Unlike negative reinforcement, which seeks to increase a behaviour by removing a negative condition, positive punishment aims to weaken or suppress a behaviour by introducing an adverse consequence.

The concept of positive punishment can be succinctly defined within the framework of operant conditioning as the process of adding an undesirable stimulus to decrease the frequency of a behaviour. This form of punishment functions by creating a negative association with the behaviour that's to be modified.

An everyday example is when a parent disciplines a child for misbehaviour. If a child runs into the street without looking and is immediately scolded, the scolding is the added aversive stimulus intended to reduce the likelihood of the child engaging in that unsafe behaviour again.

Another illustration is within the classroom environment. If a student is frequently interrupting class by talking to their peers, the teacher might assign extra homework each time the student disrupts the class. The introduction of more work is the positive punishment intended to discourage interruptions.

While positive punishment can be an effective method for decreasing unwanted behaviours, it also raises several ethical considerations. It's essential for those implementing such behavioural interventions, like educators, therapists, and parents, to weigh the potential implications of using positive punishment:

Professionals and caregivers are advised to consider positive reinforcement techniques and other behaviour modification strategies that encourage desirable behaviours through rewards rather than utilising punishment. Ethical application, if punishment is used, requires it to be proportionate, consistent, and paired with clear communication so that the individual understands which behaviour is being targeted and why.

Positive punishment is a component of the principles of operant conditioning, effective for decreasing unwanted behaviours. However, its use must be approached with caution, considering the ethical implications and potential psychological impacts, privileging positive reinforcement strategies whenever possible for a more constructive approach to behaviour modification.

Negative punishment reduces unwanted behavior by removing something pleasant, such as taking away screen time for misbehavior. This technique works best when the removed item is genuinely valued by the individual and the connection to the behavior is clear. It tends to be less emotionally charged than positive punishment and can be effective for reducing attention-seeking behaviors.

Operant conditioning encompasses various techniques intended to influence behaviour, among which negative punishment plays a significant role. This method involves the removal of a desirable stimulus or something rewarding immediately following a behaviour with the intention to decrease the likelihood of the behaviour's recurrence. Unlike positive punishment, which involves adding an aversive stimulus, negative punishment reduces behaviour by taking away something valued by the individual. This approach is often used in various settings, from homes to schools, to manage undesirable behaviours effectively.

Common examples include losing driving privileges for breaking curfew, having recess time reduced for not completing work, or removing a favorite toy after aggressive behavior. Time-outs are a classic form where attention and stimulation are removed following misbehavior. These consequences work by making the individual realize that undesirable behaviors lead to the loss of things they enjoy.

Negative punishment is characterised by the removal of a positive stimulus in response to an undesired behaviour with the aim of diminishing the behaviour. For instance, consider a teenager who enjoys playing video games daily. If the teenager fails to complete their chores, their parent might retract their gaming privileges. This withdrawal acts as negative punishment because the removal of a valued pleasure, the opportunity to play video games, is intended to encourage the completion of chores in the future.

Another example is seen in the workplace, where an employee who habitually arrives late might lose the privilege of flexible work hours. The loss of flexibility serves as negative punishment, setting the expectation that punctuality will lead to the reinstatement of the flexible schedule.

Effective alternatives include positive reinforcement for desired behaviors, natural consequences, and teaching replacement behaviors through modeling. Restorative practices that focus on repairing harm and building empathy can address underlying issues better than removal of privileges. Proactive strategies like clear expectations, engaging instruction, and relationship building prevent many behavior problems before they start.

While negative punishment is a tool for reducing undesirable behaviour, it isn't the only method available within operant conditioning. Alternatives to negative punishment can often yield more sustainable behaviour change. Edwin Guthrie proposed altering behaviour patterns by gradually intensifying a weak stimulus. Rather than simply removing a reward or pleasure, this method aims to shift behaviour steadily and gently.

Furthermore, the exclusive use of punishment can fail to teach the preferred, positive behaviour; it may instead only suppress the unwanted behaviour temporarily. That's why operant conditioning also emphasises positive reinforcement, rewarding good behaviour to encourage its repetition.

Instead of solely depending on negative consequences, behaviour modification techniques often incorporate positive reinforcement strategies. For example, implementing a rewards system contingent upon the demonstration of positive behaviours can be more motivating and less detrimental than punishment. The promise of additional privileges or tangible rewards can incentivise individuals to modify their behaviour.

In behaviour modification, a balance of positive reinforcement (introducing a positive outcome) and negative reinforcement (removing an aversive outcome) should be considered, in addition to punishment tactics. This balance ensures a comprehensive approach to shaping behaviour not just through the avoidance of negative outcomes, but also through the pursuit of positive ones.

Reinforcement builds positive associations with desired behaviors and maintains better relationships between teachers and students. Research shows reinforced behaviors are more likely to generalize to other settings and persist over time compared to punished behaviors. Reinforcement also promotes intrinsic motivation and self-esteem while punishment can create fear, resentment, and avoidance of learning situations.

Within this framework lies the concept of reinforcement, a process that increases the likelihood of a behaviour recurring. Reinforcements can be positive or negative, with each serving a unique purpose in behaviour modification.

Positive reinforcement involves the introduction of a favourable event or outcome after a desired behaviour, thereby reinforcing that behaviour. The adding of something enjoyable or rewarding encourages repetition of the behaviour. On the other hand, negative reinforcement occurs when an unfavourable event or outcome is removed following a good behaviour. The removal of something aversive consequently strengthens the likelihood of the behaviour being repeated.

In both types of reinforcement, behaviours are encouraged and strengthened. Moreover, these reinforcements can be broken down into primary and secondary categories, and they can be delivered according to different reinforcement schedules to effectively shape and maintain behaviours. Notably, operant conditioning isn't just a theoretical construct; it's applied practically in diverse fields, including education, parenting, workplace management, relationship development, and therapeutic interventions for behavioural issues.

Primary Reinforcers play a direct and innate role in encouraging behaviours by satisfying biological needs, without needing to be learned. Secondary Reinforcers are associated with primary ones and acquire their value through this connection, often dependent on the individual's experiences or culture. Also, operant conditioning includes reinforcement strategies like token economies, which utilise secondary reinforcers to motivate and sustain behaviours through a system of exchange for primary rewards.

Now that we have a foundational understanding, let's examine the specifics of primary and secondary reinforcers.

Primary reinforcers are innately satisfying as they fulfil basic biological needs and desires without requiring any learning process. These are the fundamental aspects of survival and comfort that are universally compelling. Food, water, sleep, and shelter are quintessential examples, as they satisfy hunger, thirst, fatigue, and the need for security, respectively. The fundamental nature of these needs ensures that primary reinforcers retain their reinforcing power naturally.

Take the pleasure principle, for instance. Engaging in activities that produce pleasure, such as eating a delicious meal or experiencing sexual gratification, reinforces the behaviour that led to that pleasure due to the immediate satisfaction it provides. Similarly, on a hot day, jumping into a cool body of water brings instant relief and enjoyment. Here, the coolness of the water acts as a primary reinforcer, as it satisfies the need to reduce body temperature and the innate desire for comfort.

These primary reinforcers are central to operant conditioning because they don't need to be paired with any other stimuli to be effective; their potency is inherent. They're the building blocks upon which more complex reinforcement systems are built, and they serve as powerful motivators for desired behaviours.

Secondary reinforcers, unlike primary ones, don't innately satisfy physical needs. Instead, they have value to an individual owing to their association with primary reinforcers. These are learned reinforcements and are highly variable from person to person, shaped by individual experiences, cultural background, and learned associations.

Praise, for example, may serve as a secondary reinforcer when it's linked to the affection or approval that fulfils a social need. Money is perhaps the most ubiquitous secondary reinforcer; it has no intrinsic value but can be used to purchase a wide array of primary reinforcers like food, water, and shelter, thereby acquiring its reinforcing power. Similarly, points or stickers are often used in educational settings as tokens, serving as secondary reinforcers with the understanding that accumulating enough of them can lead to a primary reinforcer, such as a special privilege or reward.

Secondary reinforcers also encompass generalised reinforcers, which aren't limited in scope to a single primary reward but can be used in several exchanges. Money is again the classic example, as it harnesses the ability to facilitate the acquisition of numerous primary reinforcers, be it nutritious meals, comfortable living conditions, or enjoyable experiences.

Reinforcement, whether primary or secondary, isn't applied in isolation. Using reinforcement schedules, such as fixed or variable intervals, allows for the careful and strategic delivery of reinforcement to maintain and shape behaviours. This intricate web of reinforcements and schedules forms the very fabric of operant conditioning, making it an immensely powerful tool in influencing human behaviour.

The four main schedules are fixed ratio (reinforcement after set number of responses), variable ratio (after varying number of responses), fixed interval (after set time period), and variable interval (after varying time periods). Variable schedules create more persistent behaviors that resist extinction, while fixed schedules produce predictable response patterns. Each schedule has specific advantages for different learning goals and situations.

Operant conditioning extends its influence on behaviour through the strategic use of reinforcement schedules. These schedules are critical because they define the rules that govern the timing and frequency of reinforcements, whether it's a reward or the removal of an aversive stimulus.

Organised into two main categories based on time and ratio, these schedules are known as fixed and variable intervals and fixed and variable ratios. These schedules can greatly affect the response rates and patterns of the subjects involved, providing a systematic approach to reinforcing desired behaviours.

For example, a patient in a hospital might receive pain relief medication at routine intervals, while a social media user might check their feed at irregular times. Both instances are driven by underlying reinforcement schedules that shape their behaviours.

The Fixed Interval (FI) reinforcement schedule involves reinforcements being provided after specific, predictable time intervals. Under FI, a moderate and scalloped response rate is often observed due to significant pauses after the reinforcement is delivered.

Conversely, the Variable Interval (VI) schedule doles out reinforcement after unpredictable time intervals. This schedule typically results in a moderate, steady rate of response with no predictable pauses because the next reinforcement could come at any time. On the ratio side, a Fixed Ratio (FR) schedule delivers reinforcement after a set number of responses.

This leads to a high response rate, typically followed by a pause once the reinforcement has been received. Finally, the Variable Ratio (VR) schedule is perhaps the most effective at eliciting a high and steady rate of response, as reinforcements are given after an unpredictable number of responses. This is what makes gambling so compulsive; the reinforcement (winning) is doled out on a VR schedule.

The applications of these reinforcement schedules are manifold and can profoundly impact behaviour management in various settings. For instance, with the FI schedule's predictable reinforcements, behaviours can be shaped around consistent rewards, like a salaried employee getting paid monthly.

However, considerations such as the potential for pause after the reinforcement need to be taken into account, which can affect productivity. VI schedules keep individuals engaged for longer periods as they can't predict when the next reinforcement will occur, as seen in behaviours like repeatedly checking for emails or likes on social media.

FR schedules are instrumental in environments like manufacturing where piece-rate pay can motivate a flurry of activity. However, the post-reinforcement pauses can lead to a drop in productivity. Lastly, the VR schedule is exceptionally effective in maintaining high rates of engagement and preventing predictability-based drop-offs in response. This is witnessed in places like casinos, where slot machines operate on this principle. In behaviour modification, this might be used to promote consistent engagement with learning materials or therapies.

Understanding these schedules not only allows psychologists and behaviourists to predict and shape behaviours but also offers valuable insights for educators, employers, and even parents. By harnessing the power of these reinforcement schedules, desired behaviours can be cultivated and maintained effectively, leading to potentially positive outcomes in both human and animal subjects.

Start by identifying specific target behaviors and collecting baseline data on their frequency. Design a reinforcement system that rewards desired behaviors immediately and consistently, using tokens, points, or privileges that students value. Monitor progress through data collection and adjust the intervention based on results, gradually fading external reinforcements as behaviors become habitual.

Behaviour modification employs operant conditioning, a powerful method for altering human behaviour. At its core, operant conditioning utilises principles such as reinforcement and punishment to encourage desirable behaviours and diminish unwanted ones. In practice, behaviour modification techniques often incorporate token economies, using items like sticker charts as a form of positive reinforcement.

Positive reinforcement, such as praise and rewards, is fundamental in strengthening desired behaviours. On the other hand, ignoring or applying punishment can help reduce or eliminate undesired behaviours. For instance, parents often use operant conditioning by offering verbal praise for good manners or instituting a reward system for chores to foster positive behaviours in their children.

Operant conditioning not only thrives in home settings but also extends to schools, where teachers may reward high academic performance with recognition or special privileges, and in workplaces, where incentives are offered for increased productivity. Even within relationships, positive reinforcement through compliments or gifts can reinforce loving or helpful actions.

| Operant Conditioning Technique |

Application Example |

|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement |

Praise for completing homework |

| Negative Reinforcement |

Removing chores for good behaviour |

| Positive Punishment |

Extra tasks for rule violations |

| Negative Punishment |

Loss of privileges for misconduct |

Essential readings include Skinner's 'Science and Human Behavior' and 'About Behaviorism' for foundational theory. Modern applications are covered in Cooper, Heron, and Heward's 'Applied Behavior Analysis' textbook. For practical classroom strategies, consult Alberto and Troutman's 'Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers' or online courses from behavior analysis certification boards.

Operant conditioning has been applied extensively to various settings and populations, demonstrating its efficacy in modifying behaviour. The following five key studies highlight the effectiveness of operant conditioning across different contexts, including mental health, childhood behaviour, vocal accuracy, schizophrenia, and pain management.