Dunning-Kruger Effect

Explore the Dunning-Kruger Effect: Understand how misjudged self-assessment impacts performance and learn strategies to align perception with reality.

Explore the Dunning-Kruger Effect: Understand how misjudged self-assessment impacts performance and learn strategies to align perception with reality.

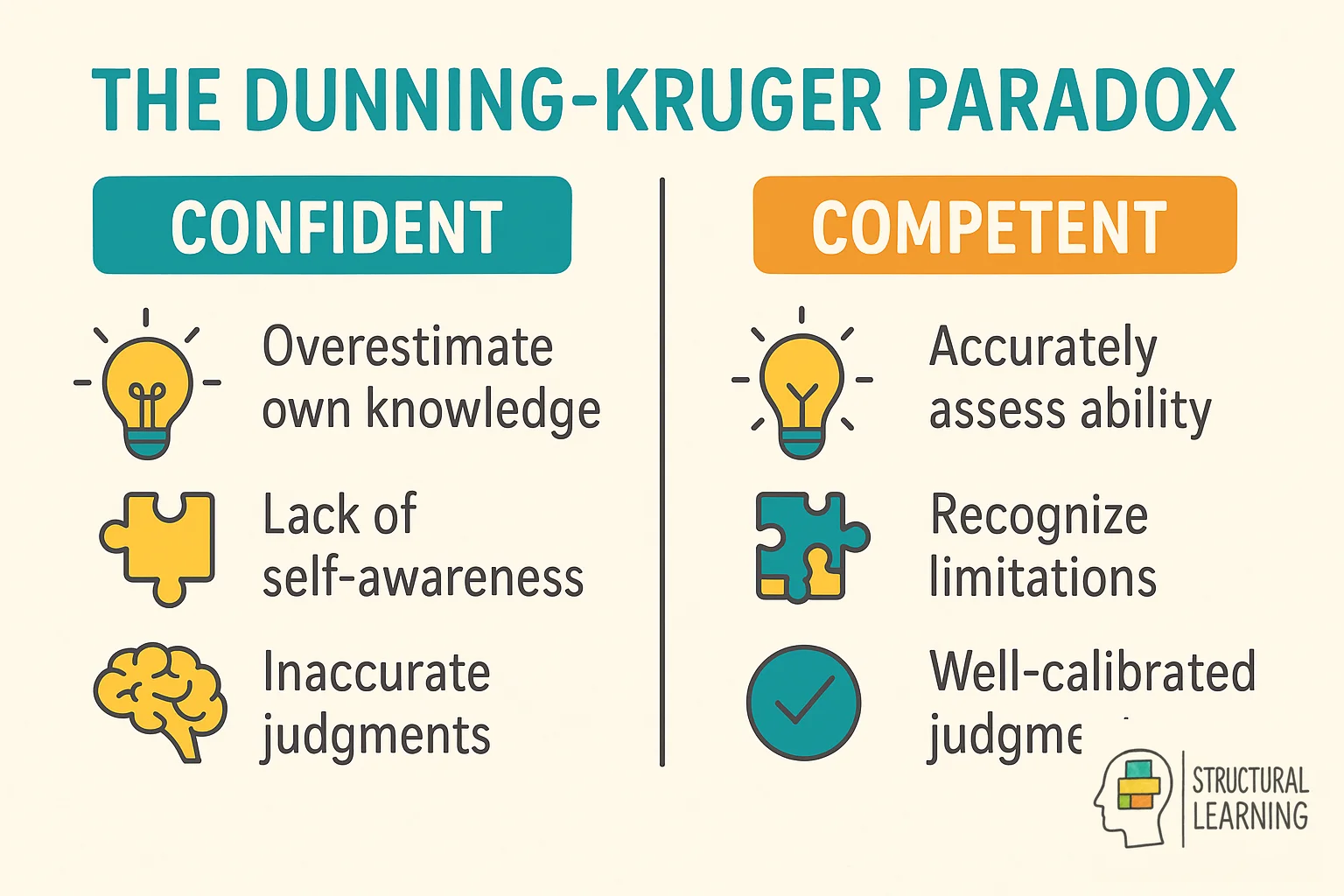

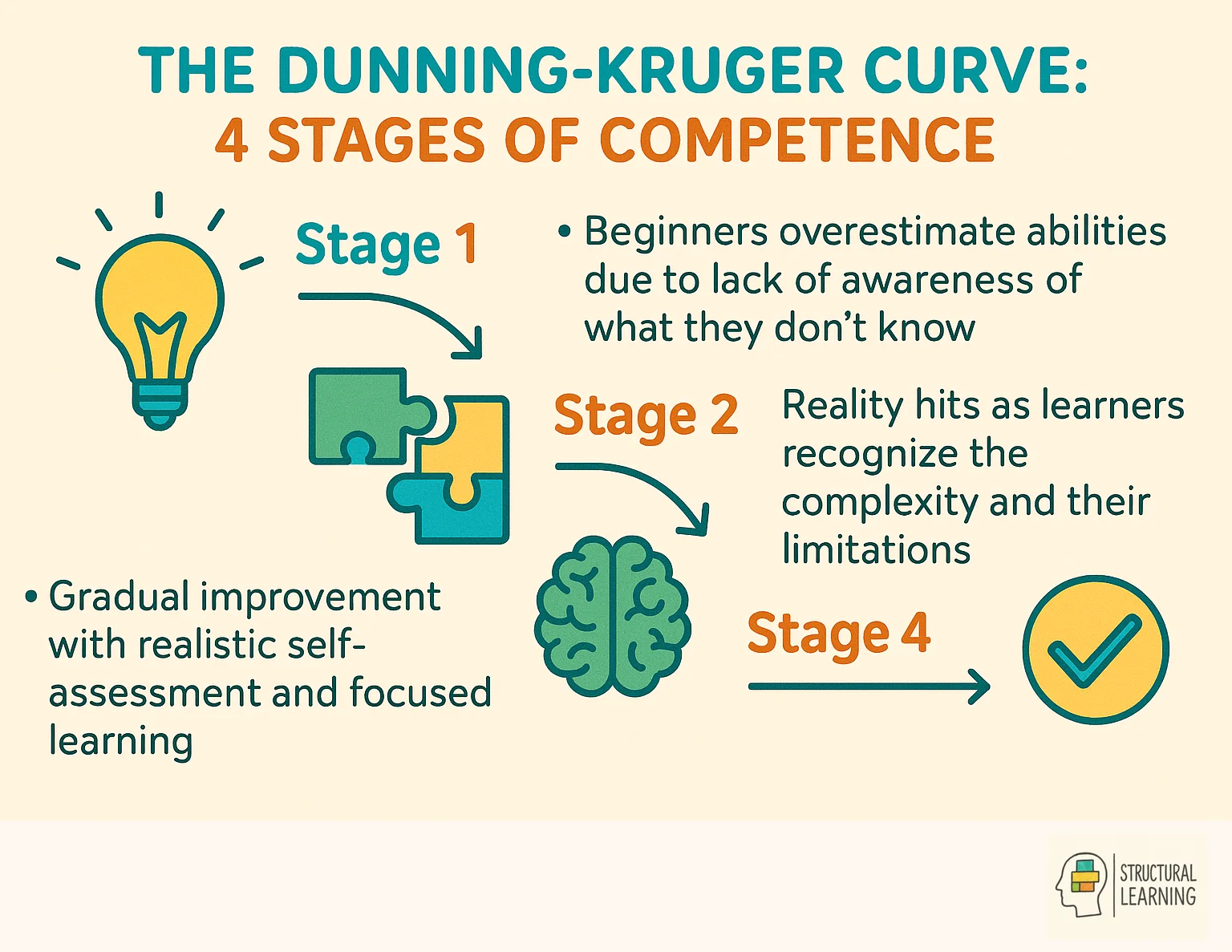

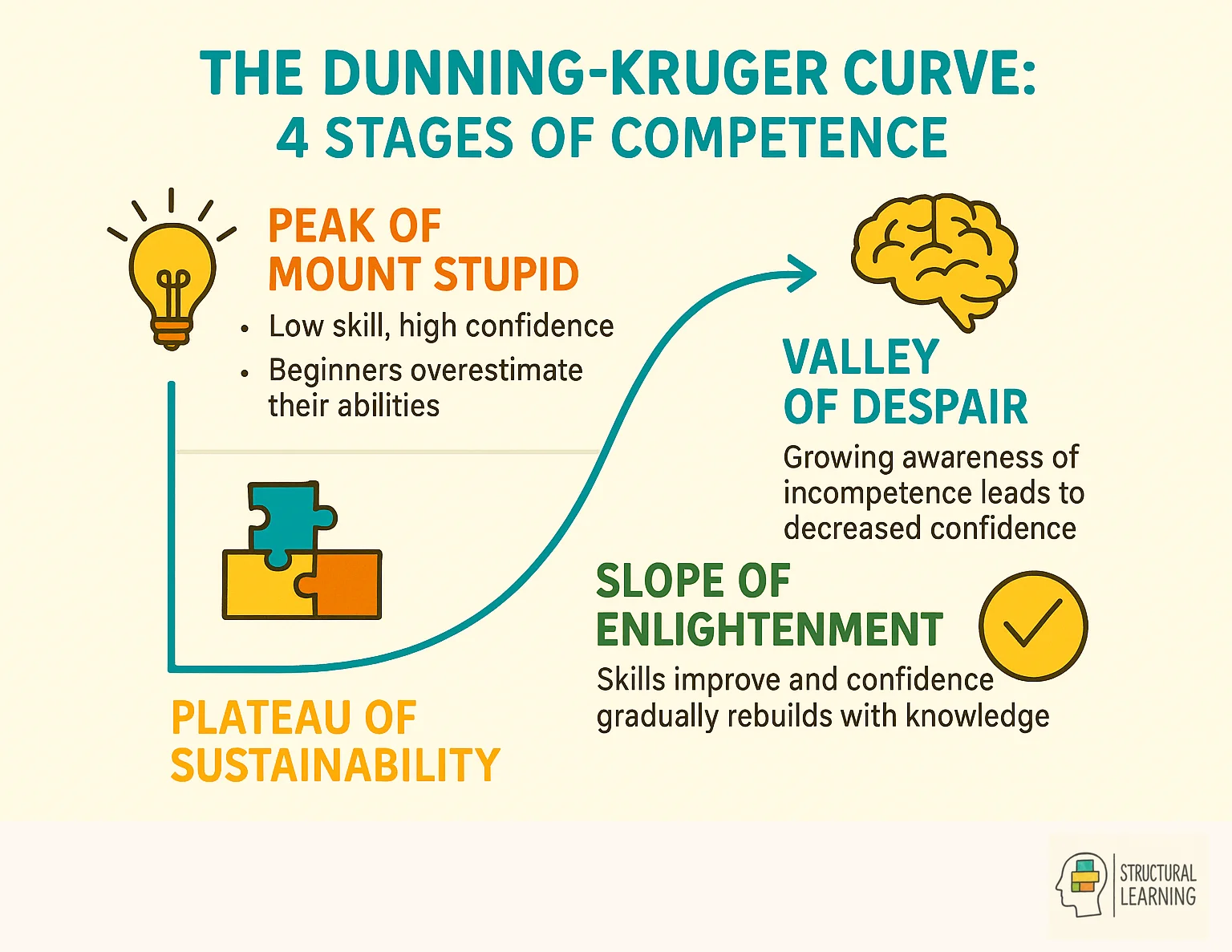

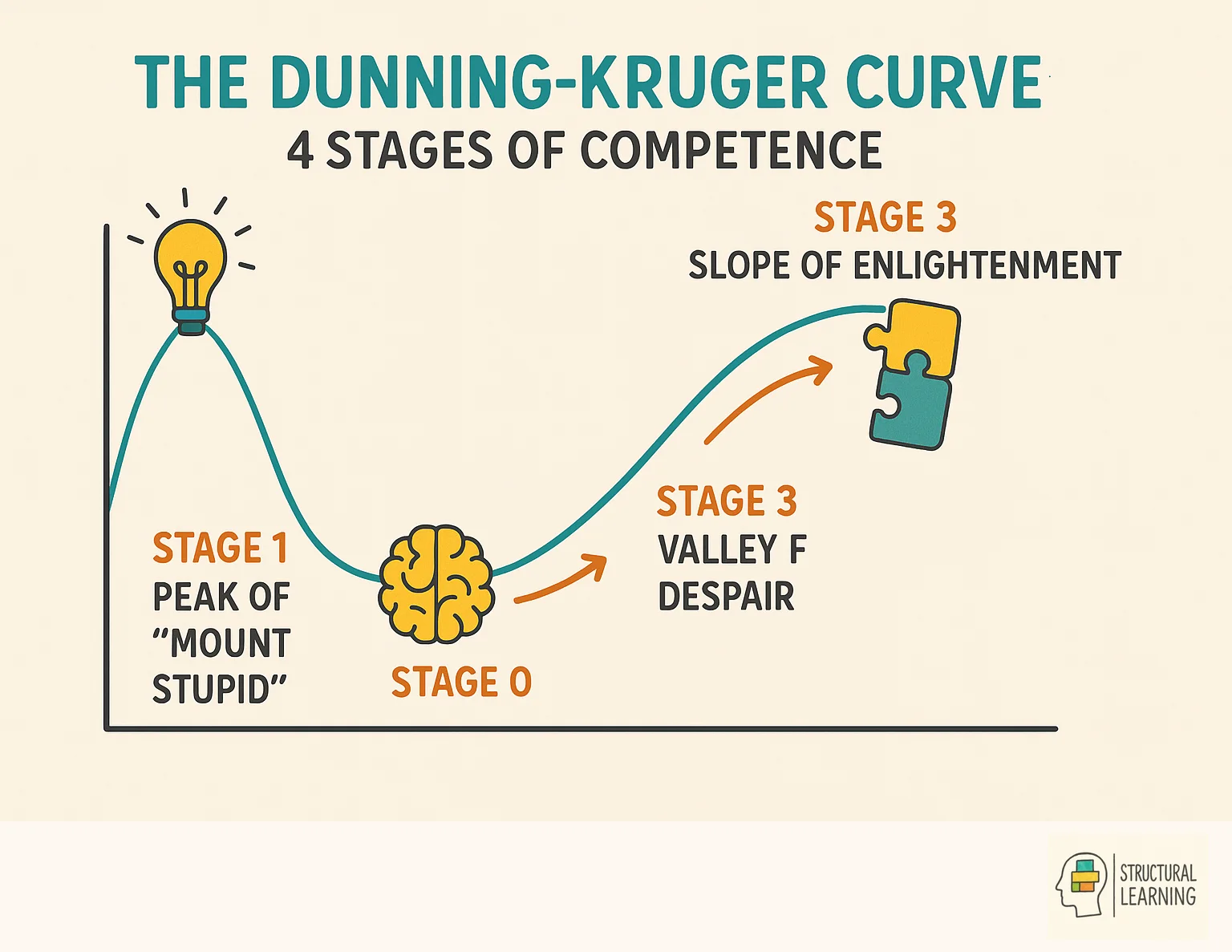

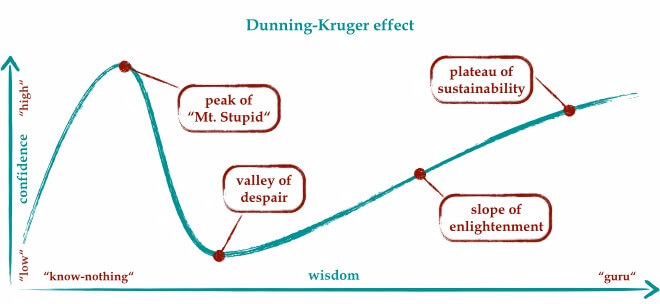

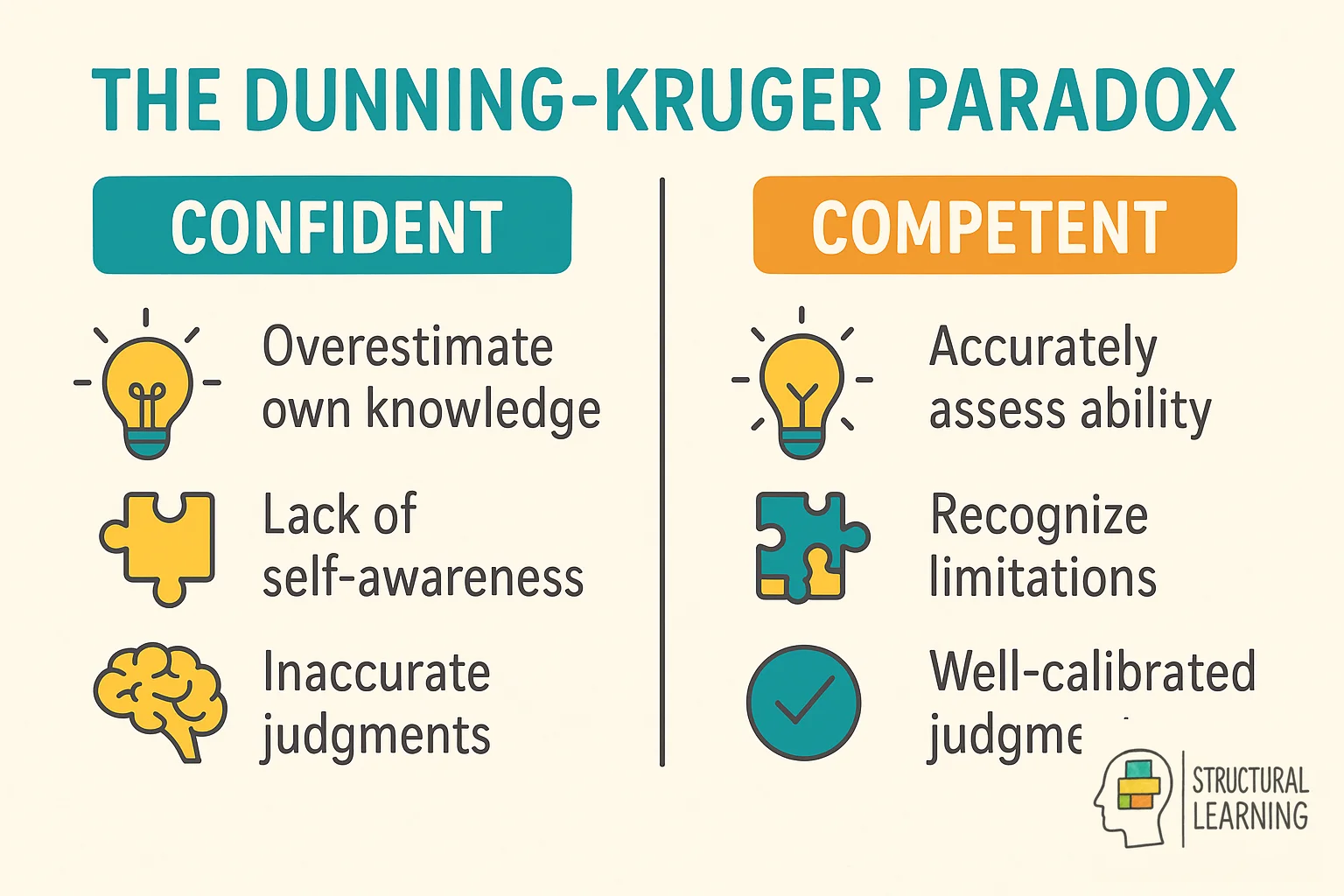

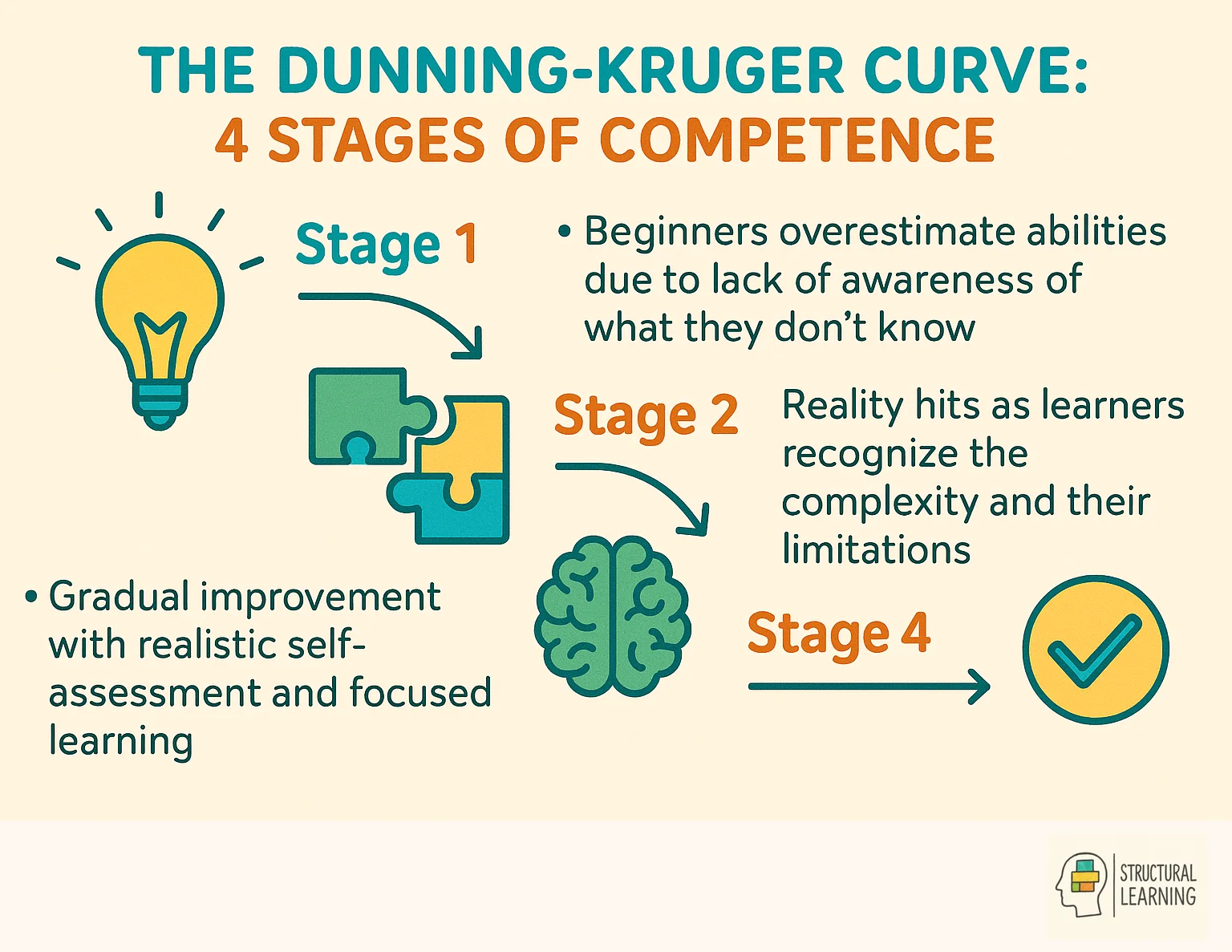

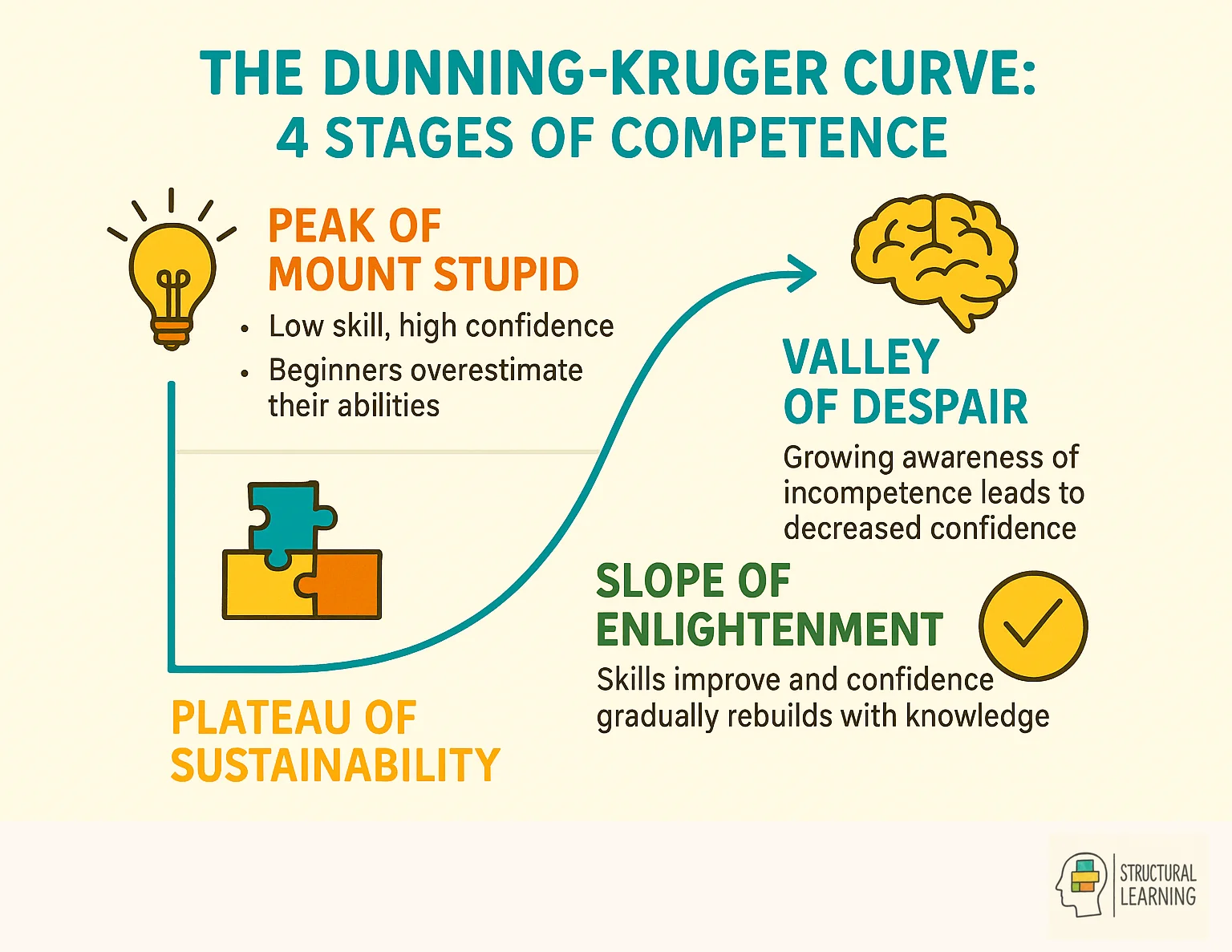

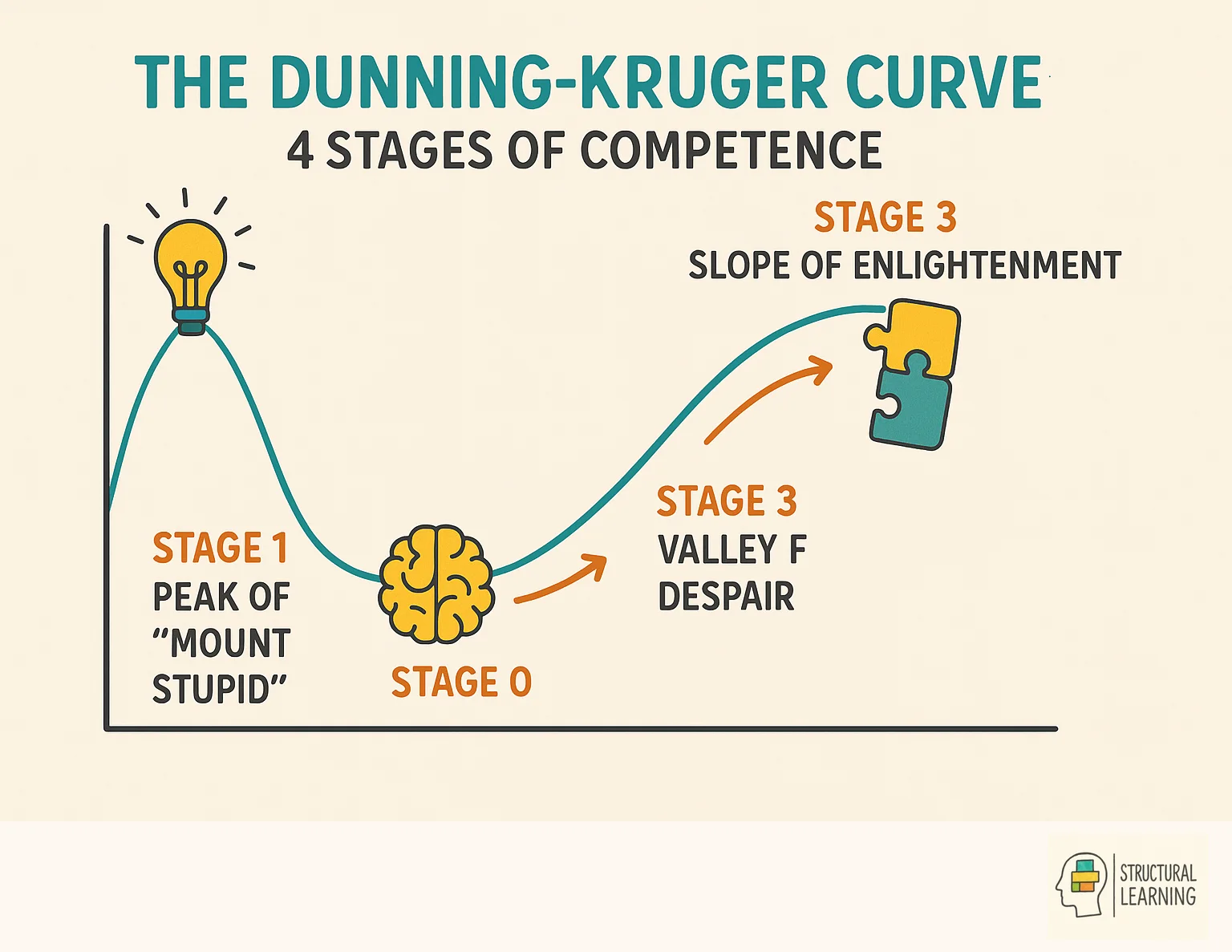

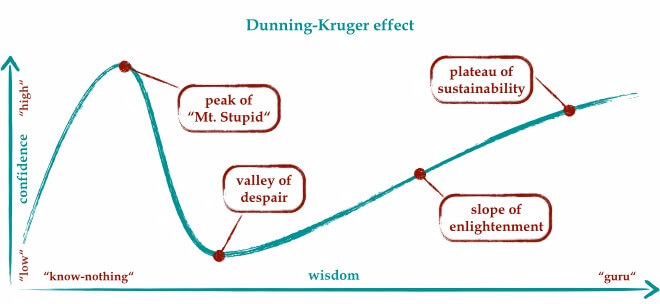

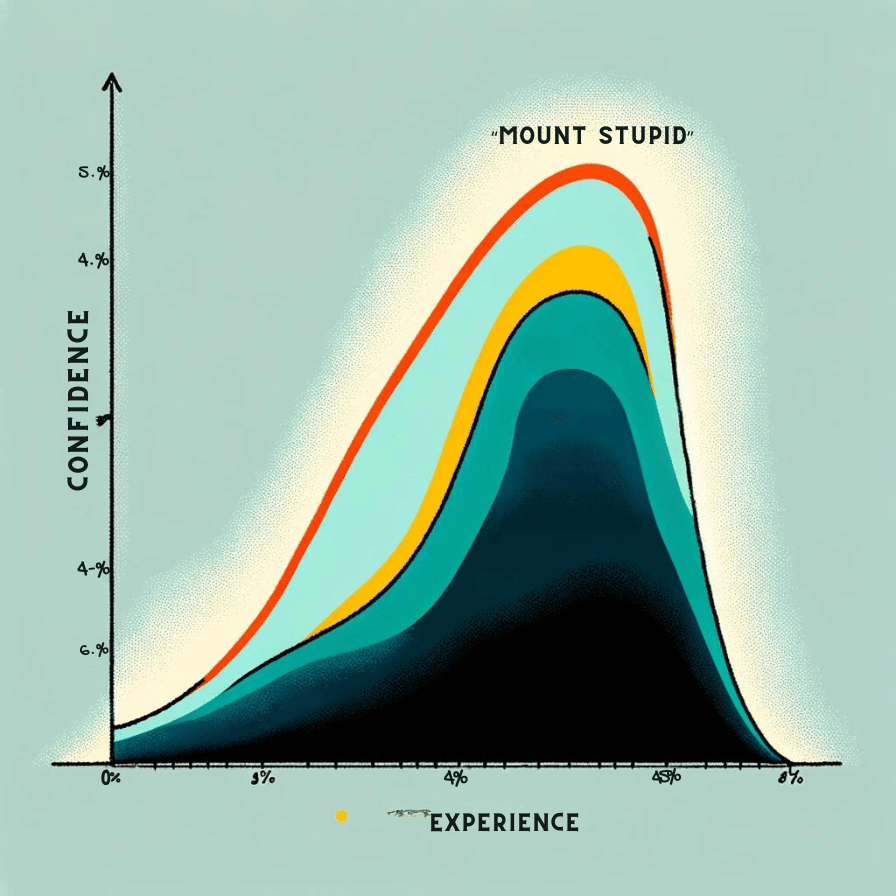

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias that reveals a paradoxical relationship between competence and confidence. Coined by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, this phenomenon highlights how poor performers often overestimate their abilities, while skilled people tend to underestimate theirs.

The crux of this effect lies in the inability of incompetent individuals to recognize their lack of skill, a blind spot that prevents them from accurately assessing their performance. Conversely, competent individuals, aware of the vast complexities of a task, might see their own skills as inadequate.

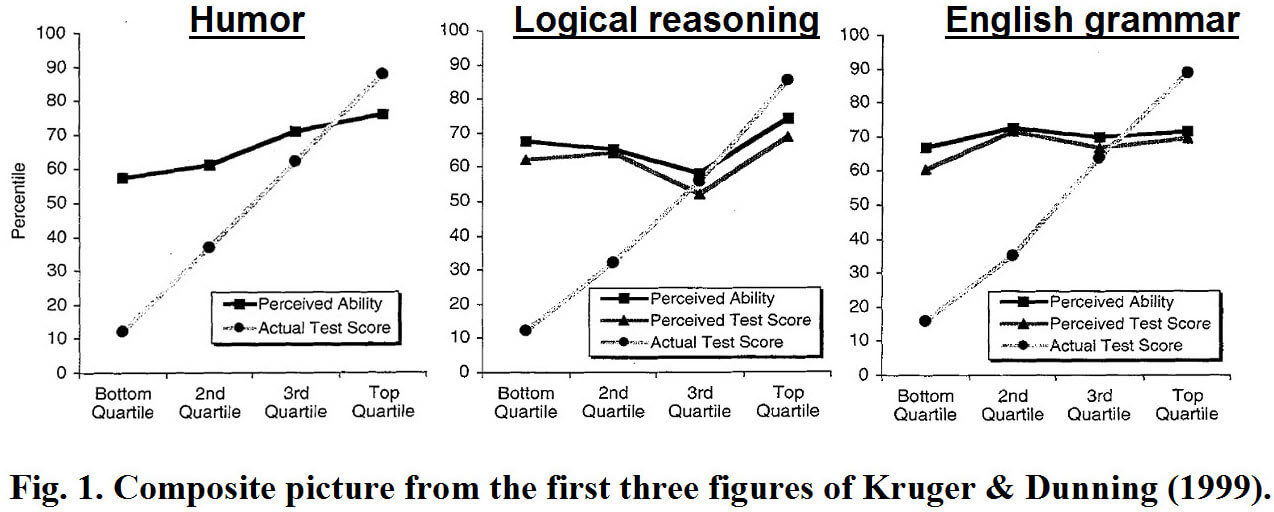

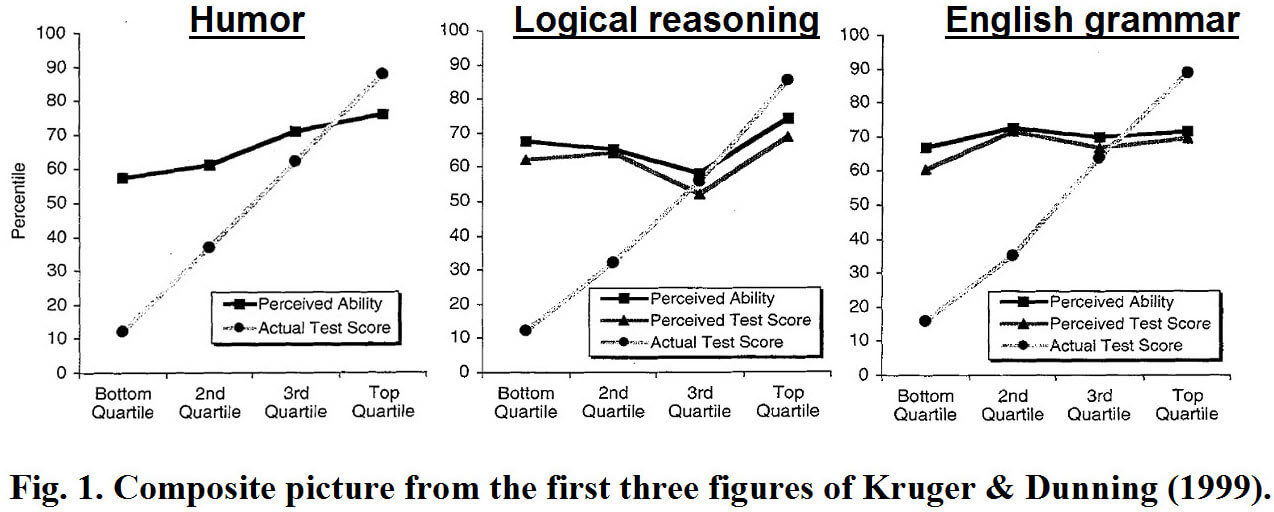

Actual studies, including assessments with college students and analyses of logical reasoning, underscore this disparity. For instance, when faced with difficult tasks, less skilled individuals failed to recognize their poor performance, attributing a lower level of difficulty to the tasks and overestimating their competence.

This "dual burden" not only affects their self-assessment but also hinders their ability to grow, as recognizing one’s deficiencies is the first step towards improvement. On the other hand, competent people, proficient in logical reasoning and aware of the nuances of challenging tasks, often undervalue their expertise due to their understanding of how much they don’t know.

The Dunning-Kruger effect emphasizes the complex interplay between one's perception of difficulty, actual level of performance, and metacognitive explanations for why errors in estimates of ability occur. It serves as a rational model to understand how:

The research origins of the Dunning-Kruger effect trace back to a series of experiments and studies that collectively shed light on the cognitive bias of illusory superiority among poor performers. This exploration into human psychology has significantly evolved over the years, marked by pivotal studies and critical analyses. Here’s how the theory has developed, highlighting key contributors and their findings:

This chronological progression underscores the robust nature of the Dunning-Kruger effect and its significance in understanding the complexities of self-perception and competence in various fields.

Poor performers often have inflated self-assessments due to a lack of self-awareness and a strong desire to protect their self-esteem. They tend to overestimate their abilities and downplay their weaknesses, leading to a distorted perception of their own performance. For example, a poor performer might believe they are highly skilled in a certain task, even though their actual performance does not reflect this belief.

Additionally, poor performers often avoid feedback that contradicts their self-perception. They may dismiss constructive criticism or become defensive when their performance is challenged, further reinforcing their inflated self-assessment. This behavior limits their ability to improve and grow, as they are not open to recognizing and addressing their shortcomings.

Ultimately, the combination of a lack of self-awareness and a desire to protect their self-esteem results in poor performers maintaining an unrealistically positive view of their own abilities. This hinders their potential for development and makes it difficult for them to accurately assess and improve their performance.

Actual performance refers to the actual level of achievement or results in a particular task, while perceived performance refers to the individual's subjective understanding or interpretation of their own performance. These two concepts often differ due to various factors such as subjective bias, external influences, and personal beliefs.

For example, in the case of an employee's performance at work, their actual performance may be measured by their productivity, efficiency, and quality of work. However, their perceived performance may be influenced by their own beliefs about their abilities, feedback from colleagues or supervisors, and external factors such as personal challenges or distractions.

Similarly, in the context of a student's academic performance, their actual performance may be reflected in their test scores and grades. However, their perceived performance may be affected by their own beliefs about their intelligence, comparison with peers, and external pressures such as parental expectations.

These discrepancies between actual and perceived performance highlight the importance of self-awareness and accurate assessment in understanding one's true capabilities and achievements. Recognizing the factors that contribute to these differences can help individuals to develop a more realistic and balanced perception of their own performance.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect has a significant impact on the relationship between competence and confidence in individuals. Those who lack skill or knowledge in a particular area may confidently believe that they are competent, while those who are highly skilled may doubt their own abilities.

This phenomenon affects decision-making and problem-solving in various ways. Individuals who overestimate their abilities may take on tasks or make decisions that are beyond their capabilities, leading to poor outcomes. On the other hand, those who underestimate their skills may fail to take on challenges or speak up with valuable insights, hindering their potential contribution.

Metacognition refers to the ability to think about and regulate one's own thinking process. It involves understanding how we learn, being aware of our own cognitive processes, and being able to regulate and control these processes. Exploring metacognitive abilities allows us to understand and develop the skills necessary to improve our learning and problem-solving abilities.

1. Understanding Metacognition

Metacognition involves understanding our own thinking processes, such as how we organize and store information, monitor our comprehension, and regulate our cognitive strategies. By exploring these abilities, we gain insights into our own learning styles and can make adjustments to improve our overall learning experience.

2. Developing Metacognitive Skills

Through exploration and practice, individuals can develop metacognitive skills such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating their own learning. These skills enable us to become more effective and efficient learners, as we can adapt our strategies based on our understanding of our cognitive processes.

3. Applying Metacognition in Problem-Solving

Exploring metacognitive abilities also allows us to apply these skills to problem-solving tasks. By being aware of our thinking processes, we can approach problems with a more strategic and systematic mindset, leading to better decision-making and solution-finding.

Exploring metacognitive abilities is essential in understanding and developing the skills necessary for effective learning and problem-solving. By gaining insight into our own cognitive processes and learning styles, we can improve our overall cognitive abilities and become more successful learners and problem-solvers.

As we have seen, Metacognition involves the ability to reflect on and control one's own cognitive processes, such as attention, memory, and problem-solving. This awareness allows individuals to regulate their thoughts and actions, leading to more effective learning and problem-solving abilities.

The importance of metacognition in the learning process cannot be overstated. By being aware of their own cognitive processes, individuals can better monitor their understanding of a topic, identify areas of confusion, and take steps to address any gaps in knowledge. This self-regulation of learning can lead to improved academic performance and a deeper understanding of the material being studied.

Furthermore, metacognition plays a crucial role in problem-solving by allowing individuals to evaluate their own thought processes and adjust their strategies as needed. By cultivating metacognitive skills, individuals can become more effective problem solvers in a variety of contexts.

Metacognitive skills play a crucial role in self-assessment by allowing individuals to accurately evaluate their own performance, identify areas for improvement, and set realistic goals. These skills enable individuals to reflect on their thinking and learning processes, which in turn helps them regulate their own learning and ultimately improve their performance.

By possessing strong metacognitive skills, individuals are better equipped to critically assess their own work, identify strengths and weaknesses, and develop a clear understanding of where improvements can be made. This self-awareness is essential for setting realistic and achievable goals, as individuals are able to accurately gauge their own abilities and establish targets that are challenging yet attainable.

Furthermore, metacognitive skills enable individuals to reflect on and regulate their learning process, allowing for continuous improvement in performance. By being able to monitor their own progress, identify areas where additional effort is needed, and adapt their learning strategies accordingly, individuals can more effectively enhance their performance in various tasks and activities.

In differentiating skill levels among individuals, various factors such as experience, training, and aptitude come into play. Experience can be assessed through the number of years an individual has spent honing their skills in a particular area.

Training refers to the specific education and instruction an individual has received, which can be measured through certifications, degrees, or specialized courses. Aptitude, on the other hand, reflects an individual's natural abilities and talents in a certain skill.

To assess skill levels, various methods can be used, including performance evaluations, skills assessments, and standardized tests. These assessments help in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of each individual and aid in creating personalized learning plans. T

hese plans should take into account a person's skill level, learning preferences, and goals, and may include specific training programs, mentorship opportunities, and professional development activities. By tailoring learning plans to the individual, individuals are more likely to excel and grow in their skill set. This personalized approach ensures that each person's unique abilities and potential are recognized and nurtured.

The measurement of the Dunning-Kruger effect has intrigued psychologists and researchers, leading to various experimental designs and studies aimed at quantifying this cognitive bias. These efforts seek to understand how individuals with differing levels of competence assess their performance and how this assessment contrasts with objective measures. Here's a look at key methodologies and studies that have sought to measure the Dunning-Kruger effect:

These research efforts provide a multifaceted view of the Dunning-Kruger effect, illustrating the complexity of measuring self-awareness and cognitive biases in estimating one's abilities. Through these studies, researchers aim to uncover more about how individuals can achieve more accurate self-evaluations and the implications for education and professional development.

Implementing these strategies can create a learning environment that not only addresses the Dunning-Kruger effect but also promotes a culture of continuous improvement and self-awareness among students.

Here are five key studies on the Dunning-Kruger effect providing insights into overconfidence, estimation errors, and skill levels:

These studies collectively deepen our understanding of the Dunning-Kruger effect, highlighting its robustness across different domains and challenging both previous and actual studies to consider the complexities of self-assessment and the influence of metacognitive abilities on overconfidence.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias that reveals a paradoxical relationship between competence and confidence. Coined by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, this phenomenon highlights how poor performers often overestimate their abilities, while skilled people tend to underestimate theirs.

The crux of this effect lies in the inability of incompetent individuals to recognize their lack of skill, a blind spot that prevents them from accurately assessing their performance. Conversely, competent individuals, aware of the vast complexities of a task, might see their own skills as inadequate.

Actual studies, including assessments with college students and analyses of logical reasoning, underscore this disparity. For instance, when faced with difficult tasks, less skilled individuals failed to recognize their poor performance, attributing a lower level of difficulty to the tasks and overestimating their competence.

This "dual burden" not only affects their self-assessment but also hinders their ability to grow, as recognizing one’s deficiencies is the first step towards improvement. On the other hand, competent people, proficient in logical reasoning and aware of the nuances of challenging tasks, often undervalue their expertise due to their understanding of how much they don’t know.

The Dunning-Kruger effect emphasizes the complex interplay between one's perception of difficulty, actual level of performance, and metacognitive explanations for why errors in estimates of ability occur. It serves as a rational model to understand how:

The research origins of the Dunning-Kruger effect trace back to a series of experiments and studies that collectively shed light on the cognitive bias of illusory superiority among poor performers. This exploration into human psychology has significantly evolved over the years, marked by pivotal studies and critical analyses. Here’s how the theory has developed, highlighting key contributors and their findings:

This chronological progression underscores the robust nature of the Dunning-Kruger effect and its significance in understanding the complexities of self-perception and competence in various fields.

Poor performers often have inflated self-assessments due to a lack of self-awareness and a strong desire to protect their self-esteem. They tend to overestimate their abilities and downplay their weaknesses, leading to a distorted perception of their own performance. For example, a poor performer might believe they are highly skilled in a certain task, even though their actual performance does not reflect this belief.

Additionally, poor performers often avoid feedback that contradicts their self-perception. They may dismiss constructive criticism or become defensive when their performance is challenged, further reinforcing their inflated self-assessment. This behavior limits their ability to improve and grow, as they are not open to recognizing and addressing their shortcomings.

Ultimately, the combination of a lack of self-awareness and a desire to protect their self-esteem results in poor performers maintaining an unrealistically positive view of their own abilities. This hinders their potential for development and makes it difficult for them to accurately assess and improve their performance.

Actual performance refers to the actual level of achievement or results in a particular task, while perceived performance refers to the individual's subjective understanding or interpretation of their own performance. These two concepts often differ due to various factors such as subjective bias, external influences, and personal beliefs.

For example, in the case of an employee's performance at work, their actual performance may be measured by their productivity, efficiency, and quality of work. However, their perceived performance may be influenced by their own beliefs about their abilities, feedback from colleagues or supervisors, and external factors such as personal challenges or distractions.

Similarly, in the context of a student's academic performance, their actual performance may be reflected in their test scores and grades. However, their perceived performance may be affected by their own beliefs about their intelligence, comparison with peers, and external pressures such as parental expectations.

These discrepancies between actual and perceived performance highlight the importance of self-awareness and accurate assessment in understanding one's true capabilities and achievements. Recognizing the factors that contribute to these differences can help individuals to develop a more realistic and balanced perception of their own performance.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect has a significant impact on the relationship between competence and confidence in individuals. Those who lack skill or knowledge in a particular area may confidently believe that they are competent, while those who are highly skilled may doubt their own abilities.

This phenomenon affects decision-making and problem-solving in various ways. Individuals who overestimate their abilities may take on tasks or make decisions that are beyond their capabilities, leading to poor outcomes. On the other hand, those who underestimate their skills may fail to take on challenges or speak up with valuable insights, hindering their potential contribution.

Metacognition refers to the ability to think about and regulate one's own thinking process. It involves understanding how we learn, being aware of our own cognitive processes, and being able to regulate and control these processes. Exploring metacognitive abilities allows us to understand and develop the skills necessary to improve our learning and problem-solving abilities.

1. Understanding Metacognition

Metacognition involves understanding our own thinking processes, such as how we organize and store information, monitor our comprehension, and regulate our cognitive strategies. By exploring these abilities, we gain insights into our own learning styles and can make adjustments to improve our overall learning experience.

2. Developing Metacognitive Skills

Through exploration and practice, individuals can develop metacognitive skills such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating their own learning. These skills enable us to become more effective and efficient learners, as we can adapt our strategies based on our understanding of our cognitive processes.

3. Applying Metacognition in Problem-Solving

Exploring metacognitive abilities also allows us to apply these skills to problem-solving tasks. By being aware of our thinking processes, we can approach problems with a more strategic and systematic mindset, leading to better decision-making and solution-finding.

Exploring metacognitive abilities is essential in understanding and developing the skills necessary for effective learning and problem-solving. By gaining insight into our own cognitive processes and learning styles, we can improve our overall cognitive abilities and become more successful learners and problem-solvers.

As we have seen, Metacognition involves the ability to reflect on and control one's own cognitive processes, such as attention, memory, and problem-solving. This awareness allows individuals to regulate their thoughts and actions, leading to more effective learning and problem-solving abilities.

The importance of metacognition in the learning process cannot be overstated. By being aware of their own cognitive processes, individuals can better monitor their understanding of a topic, identify areas of confusion, and take steps to address any gaps in knowledge. This self-regulation of learning can lead to improved academic performance and a deeper understanding of the material being studied.

Furthermore, metacognition plays a crucial role in problem-solving by allowing individuals to evaluate their own thought processes and adjust their strategies as needed. By cultivating metacognitive skills, individuals can become more effective problem solvers in a variety of contexts.

Metacognitive skills play a crucial role in self-assessment by allowing individuals to accurately evaluate their own performance, identify areas for improvement, and set realistic goals. These skills enable individuals to reflect on their thinking and learning processes, which in turn helps them regulate their own learning and ultimately improve their performance.

By possessing strong metacognitive skills, individuals are better equipped to critically assess their own work, identify strengths and weaknesses, and develop a clear understanding of where improvements can be made. This self-awareness is essential for setting realistic and achievable goals, as individuals are able to accurately gauge their own abilities and establish targets that are challenging yet attainable.

Furthermore, metacognitive skills enable individuals to reflect on and regulate their learning process, allowing for continuous improvement in performance. By being able to monitor their own progress, identify areas where additional effort is needed, and adapt their learning strategies accordingly, individuals can more effectively enhance their performance in various tasks and activities.

In differentiating skill levels among individuals, various factors such as experience, training, and aptitude come into play. Experience can be assessed through the number of years an individual has spent honing their skills in a particular area.

Training refers to the specific education and instruction an individual has received, which can be measured through certifications, degrees, or specialized courses. Aptitude, on the other hand, reflects an individual's natural abilities and talents in a certain skill.

To assess skill levels, various methods can be used, including performance evaluations, skills assessments, and standardized tests. These assessments help in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of each individual and aid in creating personalized learning plans. T

hese plans should take into account a person's skill level, learning preferences, and goals, and may include specific training programs, mentorship opportunities, and professional development activities. By tailoring learning plans to the individual, individuals are more likely to excel and grow in their skill set. This personalized approach ensures that each person's unique abilities and potential are recognized and nurtured.

The measurement of the Dunning-Kruger effect has intrigued psychologists and researchers, leading to various experimental designs and studies aimed at quantifying this cognitive bias. These efforts seek to understand how individuals with differing levels of competence assess their performance and how this assessment contrasts with objective measures. Here's a look at key methodologies and studies that have sought to measure the Dunning-Kruger effect:

These research efforts provide a multifaceted view of the Dunning-Kruger effect, illustrating the complexity of measuring self-awareness and cognitive biases in estimating one's abilities. Through these studies, researchers aim to uncover more about how individuals can achieve more accurate self-evaluations and the implications for education and professional development.

Implementing these strategies can create a learning environment that not only addresses the Dunning-Kruger effect but also promotes a culture of continuous improvement and self-awareness among students.

Here are five key studies on the Dunning-Kruger effect providing insights into overconfidence, estimation errors, and skill levels:

These studies collectively deepen our understanding of the Dunning-Kruger effect, highlighting its robustness across different domains and challenging both previous and actual studies to consider the complexities of self-assessment and the influence of metacognitive abilities on overconfidence.