Developing emotional intelligence in the classroom

Explore effective strategies for teachers to enhance student emotional intelligence, fostering empathy and social skills for success in and out of the classroom.

Explore effective strategies for teachers to enhance student emotional intelligence, fostering empathy and social skills for success in and out of the classroom.

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a facet of human ability that goes beyond cognitive intelligence and cognitive abilities. It encompasses the skills necessary to manage one's emotions, comprehend others' feelings, and navigate social relationships.

EI is pivotal in building stronger relationships and is particularly beneficial in difficult situations where interpersonal skills and active listening are key. It includes the ability to recognize one's own and others' emotions (Emotion Recognition Ability), the capacity for active emotional understanding, and the aptitude to communicate affect effectively through nonverbal communication.

It's a set of emotional abilities that, when harnessed, can lead to improved job satisfaction and conflict management. Unlike the more static measure of IQ, EI skills can be developed and refined with practice and mindfulness. The essence of EI lies in four core competencies:

Through the cultivation of these competencies, individuals can achieve a harmony between heart and mind, ultimately enhancing both personal and professional spheres of life.

If we consider the impact of the Covid pandemic, evidence suggests that children's and young people’s mental well-being has been significantly impacted. For example, between April and September 2021, there was an 81% increase in referrals for children and young people's mental and physical health services compared with the same period in 2019.

A relationship can also be found between well-being and pupils’ experiences of disruptive social behaviour whilst at school, with students showing poorer happiness and anxiousness because of peers’ classroom behaviour. (GOV 2021)

Between March and June 2020, a period when schools were closed to most pupils, symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were found to have significantly increased in children and young people aged between 7.5 and 12 years old compared to immediately before the pandemic. The effects of lockdown and a decline in well-being can be seen in data collected across 2020 and 2021, showing students could concentrate very (25%) or quite (59%) well in lessons in their classroom (84% very/quite well), whilst 16% said they could not concentrate very or well at all. Further, 39% of pupils were very worried about catching up on their learning.

As a practitioner being able to use emotionally intelligent strategies with students by talking about experiences, developing confidence, and supporting them to develop mindfulness strategies has and can support a positive classroom experience.By September 2020, relative to the March to June 2020 lockdown, reported behavioural, attention, and emotional difficulties in children had returned to, and stabilized at, a lower level. (Gov 2021).

As a result of the pandemic, emotional intelligence, therefore, has never been more important as a tool in the practitioners’ toolbox. As understanding a pupil’s feelings and emotions and being empathetic can increase engagement and well-being.

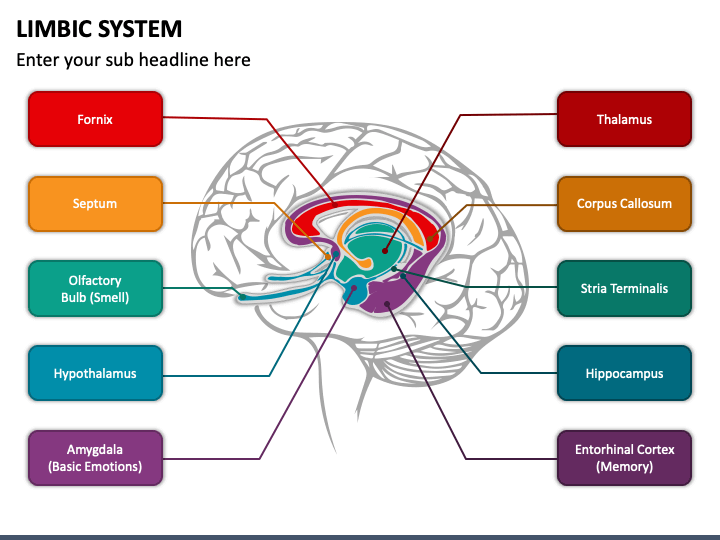

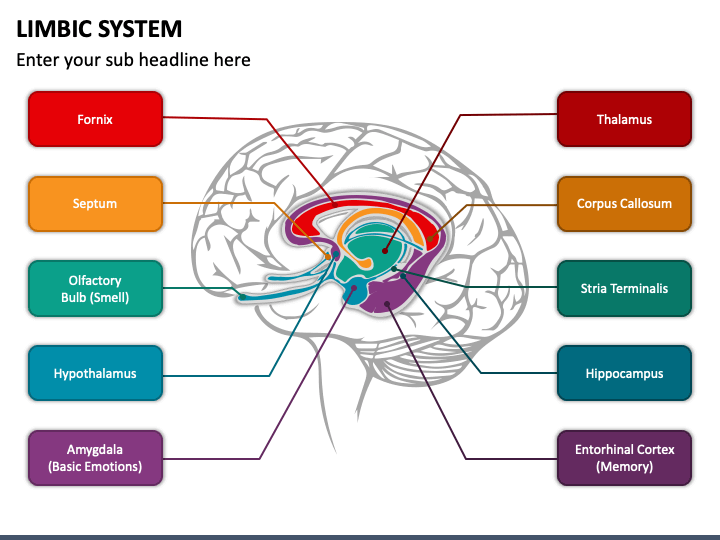

As practitioners, it is useful to understand the components of the brain that are linked to emotional intelligence, including, among others, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and frontal cortex, and amygdala.

The diagram below shows areas of the limbic system which is the part of the brain involved in our behavioural and emotional responses, especially when it comes to social behaviours we need for survival: and fight or flight responses. Often in neurodiverse students, the amygdala is associated with the body's fear and stress responses, taking over the body's responses to a variety of situations, which to others may not be threatening. For the practitioner to be aware of neurodiverse needs within their student group can then able these students to be supported through a range of strategies, including coaching, mentoring, and transactional analysis.

While the amygdala is often associated with the body’s fear and stress responses, it also plays a pivotal role in memory, often tagging that memory so it is remembered. This partially explains why the similar response to threatening situations perpetuate themselves. Therefore, neuro-diverse learners will have a remembered response from their past to situations which they repeat.

The amygdala is often thought of as being a survival-oriented brain area. Things that have strong emotions associated with them, good and bad, are likely to be the things that allow a species to not only stay alive but also thrive in its environment. Through emotional intelligence, practitioners can support students to have positive memories about a learning experience by using such tools as the 'it’s alright to fail' technique, scaffolding, and conveying the message 'we don't just have one attempt at a task performance'.

Goleman D (2011) identified that as practitioners we should be supporting our students to understand their emotions and thereby identify the appropriateness of their actions. Examples can be drawn from neurodiversity whereby the student often use flight or fight as a means of expressing their frustrations and anxieties. Such displays of emotions can have a massive impact on the whole class environment as the individual potentially interrupts the whole learning situation.

Tied in with this notion is one of a Growth Mindset (Dweck 2011) and the need to give our students a safe environment in which to fail. This humanistic approach to learning echoes Black and Williams’s (2006) research, in that ensuing students can fail and that acting on feedback will promote learning.

Salovey P and JoMayer (1990) defined emotional intelligence that can be used in positive psychology as a “subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one's own emotions and others' emotions, and how it affects one's task performance to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one's own thinking and actions” (Bechtoldt et al, 2011).

Whether you are a teacher or just learning to add on your leadership skill, emotional perception is important to everyone. Thorndike (Sharma 2008) researched dimensions of emotional intelligence as a form of “social intelligence”. He classified intelligence into three dimensions: abstract intelligence refers to managing and understanding ideas; mechanical intelligence includes managing and understanding concrete objects, and social intelligence refers to managing and understanding people.

According to Thorndike, social intelligence is the ability to perceive one’s own and others’ behaviours and motives to successfully make use of that information in social situations. Kaufman (2001) spoke of the influence of both intellective and non-intellective factors on one’s intelligence and the impact that both types of factors have on a person’s ability to act intelligently (Bar-On, 2006; Cherniss, 2000). Gardner (1983) expanded the knowledge of interpersonal skills and intrapersonal skills by introducing his theory of multiple intelligences.

Cantor and Kihlstrom (1987) define social intelligence as possessing knowledge of social skills and having the ability-based measures to get along well with others. John Mayer and Salovey P (1993) refer to social intelligence as adapting to social situations and using social skills to act accordingly. According to Salovey P and Mayer (1990), a more accurate assessment and talking about expressing emotions is emotional intelligence which uses social awareness and social intelligence.

Models of Emotional Intelligence

It is useful to consider diverse types of emotional intelligence and how they can be applied to practice.

Faltas (2017) argues that there are three major models/ types of intelligence:

These three models have been developed from research, analysis, and scientific studies. Some of these models, like the Bar-on model can be used as emotional intelligence tests.

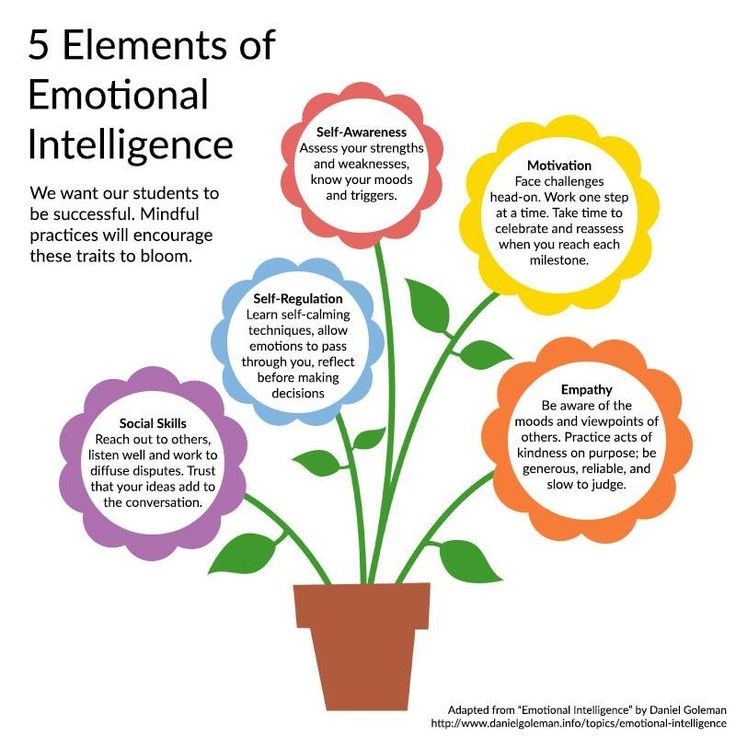

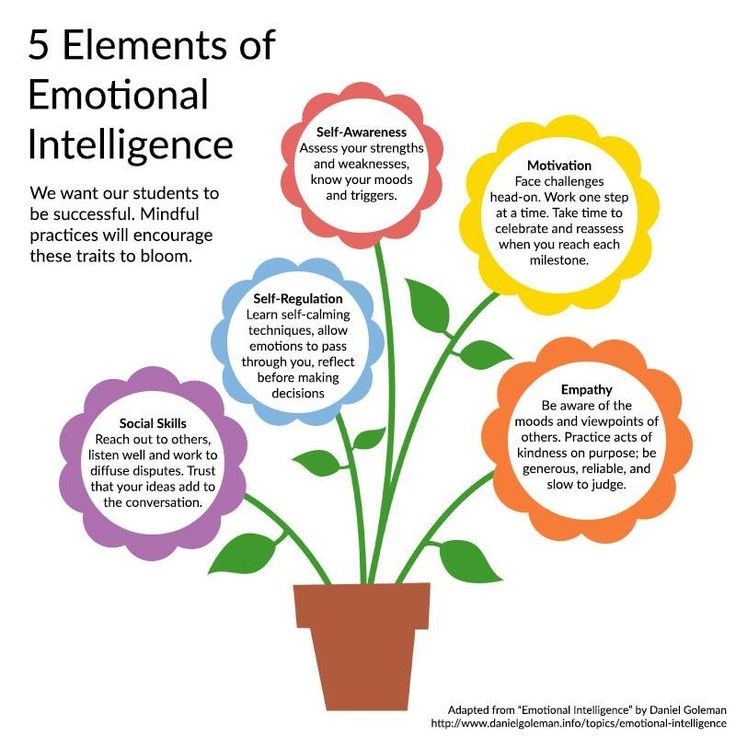

Daniel Goleman’s self-rated performance model of emotional intelligence includes five realms that focus on how we react to and in different social situations.

These can be broken down into four quadrants as shown by the diagram below which can be used as a guide to support the practitioner:

In research, Gill, Ramsey, and Leberman (2015) used self-awareness competency to explore and develop a causal loop diagram.

Source: Gill et al., 2015

This diagram above explores a unique way of thinking in that there is a relationship between different learning themes. If we apply this model to practice, practitioners should discuss with their students their thoughts and feelings and explore respect for each other.

Mayer and colleagues (2004) developed the ability model as a tool for talking about how emotions and interactions.

They suggest that the abilities and skills of Emotional intelligence can be divided into four areas – the ability to:

Bar-On model looks at five core factors of emotional intelligence by focusing on our reaction to change:

First, emotional intelligence helps students cope with emotions in the academic environment. Students can feel anxious about exams, feel disappointed with poor results, feel frustrated when they try hard but cannot achieve what they want, or feel bored if they don't find the subject matter interesting. Being able to regulate these emotions so they do not interfere with learning helps students achieve success in the learning environment. The following chart can be used with students to explore feelings, well-being, and mindfulness.

Second, emotional intelligence can help students maintain their relationships with teachers, students, and family. Personal relationship management means they can call on friends and teachers to help them when they struggle, can learn from others in group work, or can call on others for emotional support hence creating the skills of an effective leader. Using pair-share strategies, snowballing techniques, thinking environments, and general active learning technical skills are all ways relationships can be explored

Third, some humanities subjects (like literature or history) lend themselves to some level of emotional and social knowledge. It is, therefore, useful to use themes from these subjects to explore and channel emotions.

Encourage writing as a means of expression by:

Have conversations about the character by:

The intelligence of emotional intelligence is something we should use in the classroom through simple strategies that support thinking, and internal inquiry and promote understanding of self and how we interact with others. These are some frameworks available that look at ways we can approach emotional intelligence, but it is about opening communication channels within the learning environment to explore thoughts and feelings.

Here are five key studies on emotional intelligence and its implications for various aspects of learning and behavior:

These studies collectively emphasize the importance of emotional intelligence in various domains, including nursing, leadership, and workplace effectiveness. They highlight the multifaceted nature of emotional intelligence, its distinction from cognitive intelligence, and its significant impact on health, learning outcomes, and social and professional interactions.

1. Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18(Suppl), 13–25.

Bechtoldt, M. N., Rohrmann, S., De Pater, I. E., & Beersma, B. (2011). The primacy of perceiving: Emotion recognition buffers negative effects of emotional labor. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 1087–1094

2. Black and Williams(2006)Inside the Black box: Rising standards through classroom assessment.GT assessment Ltd

3. Cherniss, C. (2000). Social and emotional competence in the workplace. In R. Bar-On & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace (pp. 433–458). Jossey-Bass.

4. Dotterer, A.M., Lowe, K. (2000)Classroom Context, School Engagement, and Academic Achievement in Early Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 40, 1649–1660 .

5. Dweck (2011) Mindset how you can fulfill your potential. Robinson Publishing

6. English T, Lee IA, John OP, Gross JJ.(2016) Emotion regulation strategy selection in daily life: The role of social context and goals. Motiv Emot. 2017 Apr;41(2):230-242.

7. Faltas I (2017) Three Models of Emotional Intelligence https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314213508_Three_Models_of_Emotional_Intelligence

8. Gardner (1983) Frames of Mind. Basic Books

9. Gill, L. J., Ramsey, P. L., & Leberman, S. I. (2015). A systems approach to developing emotional intelligence using the self-awareness engine of growth model. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 28(6), 575–594.

10. Goleman (2011) Emotional intelligence why it can matter more than IQ. Bloomsbury Publishing

11. Gov (2021) State of the Nation 2021:children and young peoples well being

12. Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In R. C. Pianta, M. J. Cox, & K. L. Snow (Eds.), School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability (pp. 49–83). Paul H Brookes Publishing.

13. Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, J. C. (2001). Emotional intelligence as an aspect of general intelligence: What would David Wechsler say? Emotion, 1(3), 258–264

14. Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (2000). Social intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 359–379). Cambridge University Press.

15. Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012, ).

Classroom Emotional Climate, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology.

16. Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Journal of International Medical Research, 9(3), 145–151.

17. Schon D (1992) The Reflective Practitioner. Routledge

18. Sharma, R. R. (2008). Emotional Intelligence from 17th Century to 21st Century: Perspectives and Directions for Future Research. Vision, 12(1), 59–66.

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a facet of human ability that goes beyond cognitive intelligence and cognitive abilities. It encompasses the skills necessary to manage one's emotions, comprehend others' feelings, and navigate social relationships.

EI is pivotal in building stronger relationships and is particularly beneficial in difficult situations where interpersonal skills and active listening are key. It includes the ability to recognize one's own and others' emotions (Emotion Recognition Ability), the capacity for active emotional understanding, and the aptitude to communicate affect effectively through nonverbal communication.

It's a set of emotional abilities that, when harnessed, can lead to improved job satisfaction and conflict management. Unlike the more static measure of IQ, EI skills can be developed and refined with practice and mindfulness. The essence of EI lies in four core competencies:

Through the cultivation of these competencies, individuals can achieve a harmony between heart and mind, ultimately enhancing both personal and professional spheres of life.

If we consider the impact of the Covid pandemic, evidence suggests that children's and young people’s mental well-being has been significantly impacted. For example, between April and September 2021, there was an 81% increase in referrals for children and young people's mental and physical health services compared with the same period in 2019.

A relationship can also be found between well-being and pupils’ experiences of disruptive social behaviour whilst at school, with students showing poorer happiness and anxiousness because of peers’ classroom behaviour. (GOV 2021)

Between March and June 2020, a period when schools were closed to most pupils, symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were found to have significantly increased in children and young people aged between 7.5 and 12 years old compared to immediately before the pandemic. The effects of lockdown and a decline in well-being can be seen in data collected across 2020 and 2021, showing students could concentrate very (25%) or quite (59%) well in lessons in their classroom (84% very/quite well), whilst 16% said they could not concentrate very or well at all. Further, 39% of pupils were very worried about catching up on their learning.

As a practitioner being able to use emotionally intelligent strategies with students by talking about experiences, developing confidence, and supporting them to develop mindfulness strategies has and can support a positive classroom experience.By September 2020, relative to the March to June 2020 lockdown, reported behavioural, attention, and emotional difficulties in children had returned to, and stabilized at, a lower level. (Gov 2021).

As a result of the pandemic, emotional intelligence, therefore, has never been more important as a tool in the practitioners’ toolbox. As understanding a pupil’s feelings and emotions and being empathetic can increase engagement and well-being.

As practitioners, it is useful to understand the components of the brain that are linked to emotional intelligence, including, among others, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and frontal cortex, and amygdala.

The diagram below shows areas of the limbic system which is the part of the brain involved in our behavioural and emotional responses, especially when it comes to social behaviours we need for survival: and fight or flight responses. Often in neurodiverse students, the amygdala is associated with the body's fear and stress responses, taking over the body's responses to a variety of situations, which to others may not be threatening. For the practitioner to be aware of neurodiverse needs within their student group can then able these students to be supported through a range of strategies, including coaching, mentoring, and transactional analysis.

While the amygdala is often associated with the body’s fear and stress responses, it also plays a pivotal role in memory, often tagging that memory so it is remembered. This partially explains why the similar response to threatening situations perpetuate themselves. Therefore, neuro-diverse learners will have a remembered response from their past to situations which they repeat.

The amygdala is often thought of as being a survival-oriented brain area. Things that have strong emotions associated with them, good and bad, are likely to be the things that allow a species to not only stay alive but also thrive in its environment. Through emotional intelligence, practitioners can support students to have positive memories about a learning experience by using such tools as the 'it’s alright to fail' technique, scaffolding, and conveying the message 'we don't just have one attempt at a task performance'.

Goleman D (2011) identified that as practitioners we should be supporting our students to understand their emotions and thereby identify the appropriateness of their actions. Examples can be drawn from neurodiversity whereby the student often use flight or fight as a means of expressing their frustrations and anxieties. Such displays of emotions can have a massive impact on the whole class environment as the individual potentially interrupts the whole learning situation.

Tied in with this notion is one of a Growth Mindset (Dweck 2011) and the need to give our students a safe environment in which to fail. This humanistic approach to learning echoes Black and Williams’s (2006) research, in that ensuing students can fail and that acting on feedback will promote learning.

Salovey P and JoMayer (1990) defined emotional intelligence that can be used in positive psychology as a “subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one's own emotions and others' emotions, and how it affects one's task performance to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one's own thinking and actions” (Bechtoldt et al, 2011).

Whether you are a teacher or just learning to add on your leadership skill, emotional perception is important to everyone. Thorndike (Sharma 2008) researched dimensions of emotional intelligence as a form of “social intelligence”. He classified intelligence into three dimensions: abstract intelligence refers to managing and understanding ideas; mechanical intelligence includes managing and understanding concrete objects, and social intelligence refers to managing and understanding people.

According to Thorndike, social intelligence is the ability to perceive one’s own and others’ behaviours and motives to successfully make use of that information in social situations. Kaufman (2001) spoke of the influence of both intellective and non-intellective factors on one’s intelligence and the impact that both types of factors have on a person’s ability to act intelligently (Bar-On, 2006; Cherniss, 2000). Gardner (1983) expanded the knowledge of interpersonal skills and intrapersonal skills by introducing his theory of multiple intelligences.

Cantor and Kihlstrom (1987) define social intelligence as possessing knowledge of social skills and having the ability-based measures to get along well with others. John Mayer and Salovey P (1993) refer to social intelligence as adapting to social situations and using social skills to act accordingly. According to Salovey P and Mayer (1990), a more accurate assessment and talking about expressing emotions is emotional intelligence which uses social awareness and social intelligence.

Models of Emotional Intelligence

It is useful to consider diverse types of emotional intelligence and how they can be applied to practice.

Faltas (2017) argues that there are three major models/ types of intelligence:

These three models have been developed from research, analysis, and scientific studies. Some of these models, like the Bar-on model can be used as emotional intelligence tests.

Daniel Goleman’s self-rated performance model of emotional intelligence includes five realms that focus on how we react to and in different social situations.

These can be broken down into four quadrants as shown by the diagram below which can be used as a guide to support the practitioner:

In research, Gill, Ramsey, and Leberman (2015) used self-awareness competency to explore and develop a causal loop diagram.

Source: Gill et al., 2015

This diagram above explores a unique way of thinking in that there is a relationship between different learning themes. If we apply this model to practice, practitioners should discuss with their students their thoughts and feelings and explore respect for each other.

Mayer and colleagues (2004) developed the ability model as a tool for talking about how emotions and interactions.

They suggest that the abilities and skills of Emotional intelligence can be divided into four areas – the ability to:

Bar-On model looks at five core factors of emotional intelligence by focusing on our reaction to change:

First, emotional intelligence helps students cope with emotions in the academic environment. Students can feel anxious about exams, feel disappointed with poor results, feel frustrated when they try hard but cannot achieve what they want, or feel bored if they don't find the subject matter interesting. Being able to regulate these emotions so they do not interfere with learning helps students achieve success in the learning environment. The following chart can be used with students to explore feelings, well-being, and mindfulness.

Second, emotional intelligence can help students maintain their relationships with teachers, students, and family. Personal relationship management means they can call on friends and teachers to help them when they struggle, can learn from others in group work, or can call on others for emotional support hence creating the skills of an effective leader. Using pair-share strategies, snowballing techniques, thinking environments, and general active learning technical skills are all ways relationships can be explored

Third, some humanities subjects (like literature or history) lend themselves to some level of emotional and social knowledge. It is, therefore, useful to use themes from these subjects to explore and channel emotions.

Encourage writing as a means of expression by:

Have conversations about the character by:

The intelligence of emotional intelligence is something we should use in the classroom through simple strategies that support thinking, and internal inquiry and promote understanding of self and how we interact with others. These are some frameworks available that look at ways we can approach emotional intelligence, but it is about opening communication channels within the learning environment to explore thoughts and feelings.

Here are five key studies on emotional intelligence and its implications for various aspects of learning and behavior:

These studies collectively emphasize the importance of emotional intelligence in various domains, including nursing, leadership, and workplace effectiveness. They highlight the multifaceted nature of emotional intelligence, its distinction from cognitive intelligence, and its significant impact on health, learning outcomes, and social and professional interactions.

1. Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18(Suppl), 13–25.

Bechtoldt, M. N., Rohrmann, S., De Pater, I. E., & Beersma, B. (2011). The primacy of perceiving: Emotion recognition buffers negative effects of emotional labor. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 1087–1094

2. Black and Williams(2006)Inside the Black box: Rising standards through classroom assessment.GT assessment Ltd

3. Cherniss, C. (2000). Social and emotional competence in the workplace. In R. Bar-On & J. D. A. Parker (Eds.), The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace (pp. 433–458). Jossey-Bass.

4. Dotterer, A.M., Lowe, K. (2000)Classroom Context, School Engagement, and Academic Achievement in Early Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 40, 1649–1660 .

5. Dweck (2011) Mindset how you can fulfill your potential. Robinson Publishing

6. English T, Lee IA, John OP, Gross JJ.(2016) Emotion regulation strategy selection in daily life: The role of social context and goals. Motiv Emot. 2017 Apr;41(2):230-242.

7. Faltas I (2017) Three Models of Emotional Intelligence https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314213508_Three_Models_of_Emotional_Intelligence

8. Gardner (1983) Frames of Mind. Basic Books

9. Gill, L. J., Ramsey, P. L., & Leberman, S. I. (2015). A systems approach to developing emotional intelligence using the self-awareness engine of growth model. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 28(6), 575–594.

10. Goleman (2011) Emotional intelligence why it can matter more than IQ. Bloomsbury Publishing

11. Gov (2021) State of the Nation 2021:children and young peoples well being

12. Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). Learning opportunities in preschool and early elementary classrooms. In R. C. Pianta, M. J. Cox, & K. L. Snow (Eds.), School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability (pp. 49–83). Paul H Brookes Publishing.

13. Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, J. C. (2001). Emotional intelligence as an aspect of general intelligence: What would David Wechsler say? Emotion, 1(3), 258–264

14. Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (2000). Social intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 359–379). Cambridge University Press.

15. Reyes, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012, ).

Classroom Emotional Climate, Student Engagement, and Academic Achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology.

16. Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Journal of International Medical Research, 9(3), 145–151.

17. Schon D (1992) The Reflective Practitioner. Routledge

18. Sharma, R. R. (2008). Emotional Intelligence from 17th Century to 21st Century: Perspectives and Directions for Future Research. Vision, 12(1), 59–66.