Developing critical thinking skills in the classroom

Discover how to teach, develop, and assess critical thinking skills in schools using structured tools and curriculum-wide strategies.

Students don’t just take in information - they question it, connect ideas, and explore problems from multiple angles. In a world that demands adaptability and discernment, nurturing critical thinking skills is no longer optional; it’s essential. Yet, for many educators, the challenge isn’t knowing why it matters—it’s knowing how to teach it.

Critical thinking skills are more than a classroom skill. It’s a way of approaching the world with curiosity, care, and logic. It helps learners make sense of conflicting information, ask better questions, and develop reasoned responses. These habits aren’t just useful for exams—they’re vital for real-life decisions and thoughtful participation in society.

This article looks at both the “what” and the “how” of critical thinking. We explore its core components, consider practical strategies for teaching it across subjects, and look at how schools can assess and support its development over time. Whether you’re a teacher, curriculum leader, or simply interested in what good thinking looks like in a modern classroom, this is your starting point for building a culture of reasoning and reflection.

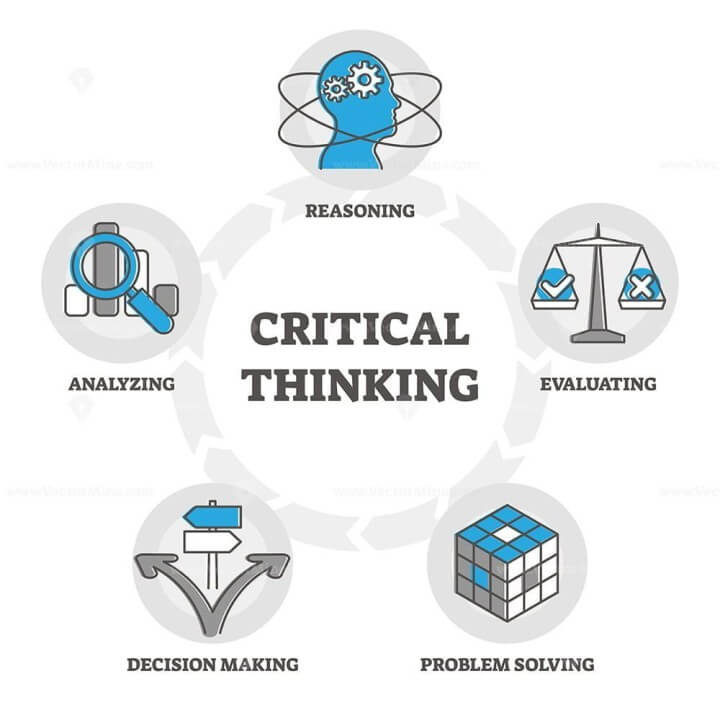

Critical thinking is a structured and rational process for connecting ideas, evaluating evidence, and forming sound, objective judgments. It requires going beyond surface-level understanding and instead analyzing information carefully to make well-informed decisions.

At its core, critical thinking is thinking about our own thinking. It helps us recognize flaws in reasoning, question assumptions, and remain aware of our own cognitive biases. This reflective skill is essential in many fields because it supports ethical, informed decision-making and the ability to generate effective solutions to complex ideas.

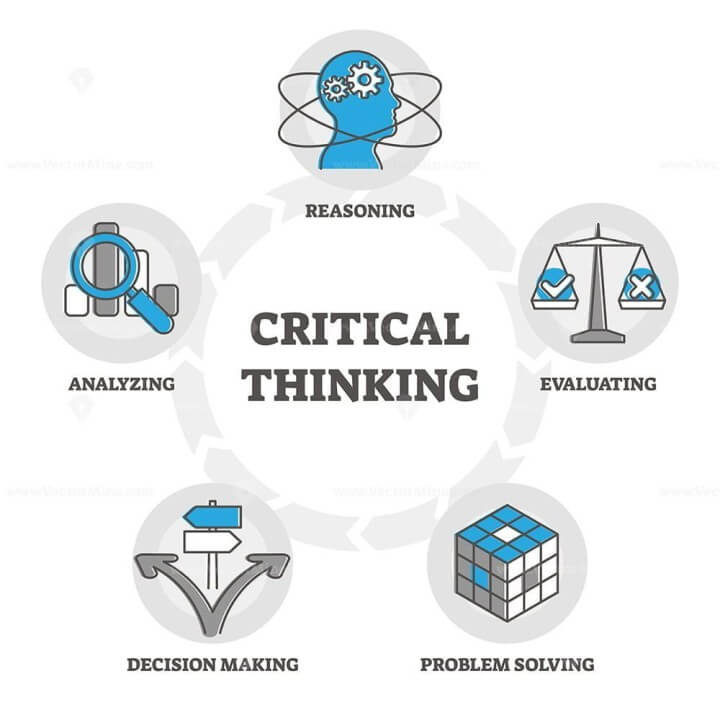

Key components of critical thinking include:

To begin developing stronger critical thinking skills, consider the following habits:

Ultimately, critical thinking is more than just a skill—it’s a disciplined cognitive process. It enables us to navigate challenges thoughtfully, engage in meaningful discussions, and respond with clarity, confidence, and ethical awareness.

Critical thinking sits at the heart of meaningful learning. It moves students beyond memorising content and into the realm of deeper understanding, where they explore ideas, make connections, and construct their own insights. In education, this isn’t just an ideal—it’s a necessity.

As classrooms evolve to meet the demands of an increasingly complex world, critical thinking offers a bridge between academic learning and real-world application. It empowers learners to evaluate information, weigh up evidence, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions. These are the habits that support independent learning, thoughtful communication, and informed decision-making.

At Structural Learning, we’re committed to embedding this kind of thinking into everyday classroom life. That means designing routines, visual tools, and physical resources that help make critical thinking visible, teachable, and sustainable. Our aim is not to bolt on thinking skills as an extra—it’s to make them part of the fabric of how learning happens.

The benefits extend far beyond the school gates. Employers consistently rank critical thinking as one of the most sought-after attributes in new hires—valuing it even above subject-specific knowledge. It underpins innovation, adaptability, and the capacity to solve problems in unfamiliar situations.

Put simply, the ability to think critically is one of the most important outcomes of education. It enables learners not only to succeed in the classroom—but to thrive beyond it.

Critical thinking is not a single skill—it’s a constellation of interrelated habits and processes that guide how we handle information, solve problems, and reach conclusions. We see these components as building blocks of deeper learning. By understanding and developing these elements, educators can help students engage with ideas more deliberately, make sound judgments, and approach problems with greater confidence.

Below are four essential components that underpin effective critical thinking in the classroom.

Being open-minded means considering different perspectives without rushing to judgment. It involves challenging assumptions, resisting snap decisions, and staying receptive to new evidence. This kind of flexibility is vital for problem-solving and empathy, especially in classroom discussions where diverse opinions emerge.

How to encourage it: Model curiosity, invite disagreement, and create routines that welcome multiple viewpoints.

Curiosity drives inquiry. It's the engine that keeps learners exploring topics more deeply, asking questions not just to get answers, but to understand the bigger picture. In critical thinking, curiosity pushes students to test their ideas, investigate contradictions, and pursue meaningful insights.

In practice: Encourage students to generate their own questions and reward thoughtful exploration over quick answers.

Analytical thinking helps students examine ideas, spot connections, and evaluate evidence. It’s what allows them to move from surface-level understanding to deeper insight. Rather than accept information at face value, analytical thinkers break problems into parts and examine how those parts relate.

In action: Use tasks that involve comparing sources, identifying patterns, or weighing pros and cons.

Problem-solving transforms thinking into doing. It involves identifying issues, developing possible solutions, and refining those ideas through testing and feedback. Critical thinkers don’t just find answers—they explore alternatives and adjust their thinking when needed.

Support it by: Framing classroom tasks as challenges with more than one right answer. Offer time to explore, revise, and share strategies.

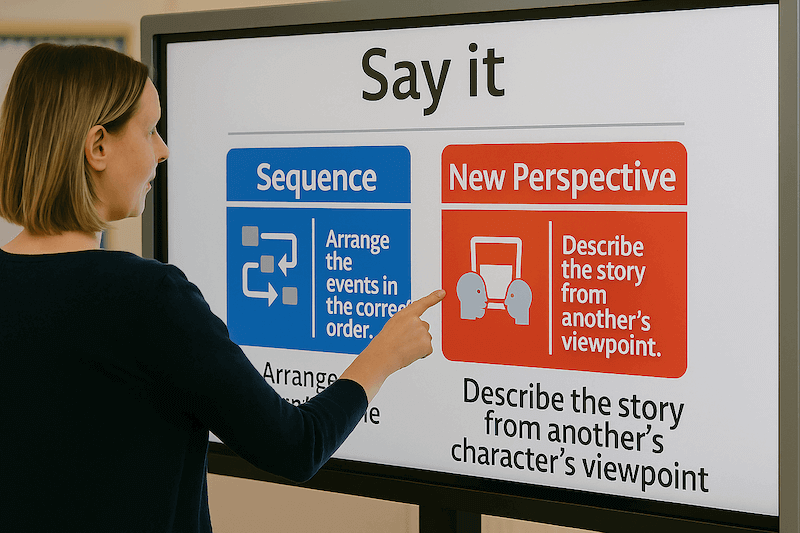

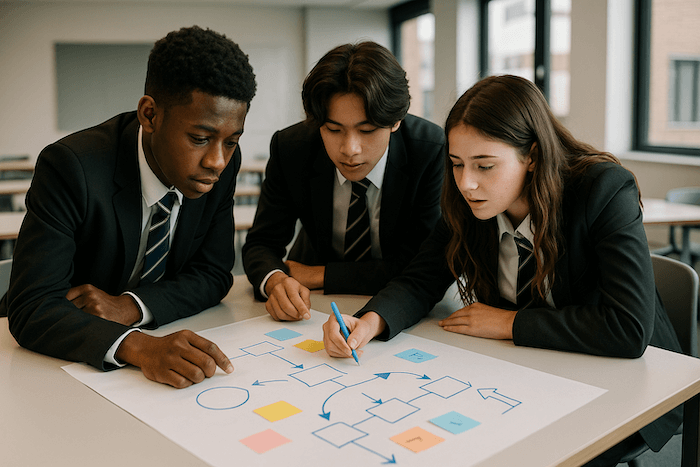

Promoting critical thinking isn't about adding extra content to an already busy timetable—it's about reshaping how students engage with learning. At Structural Learning, we help schools build a culture where thinking is visible, purposeful, and embedded in everyday classroom practice. Using tools such as the Thinking Framework, Writer’s Block, and visual scaffolds like graphic organizers, teachers can equip learners with practical ways to question, reflect, and reason—across every subject.

Here are some grounded, subject-specific strategies that make critical thinking not just teachable, but tangible.

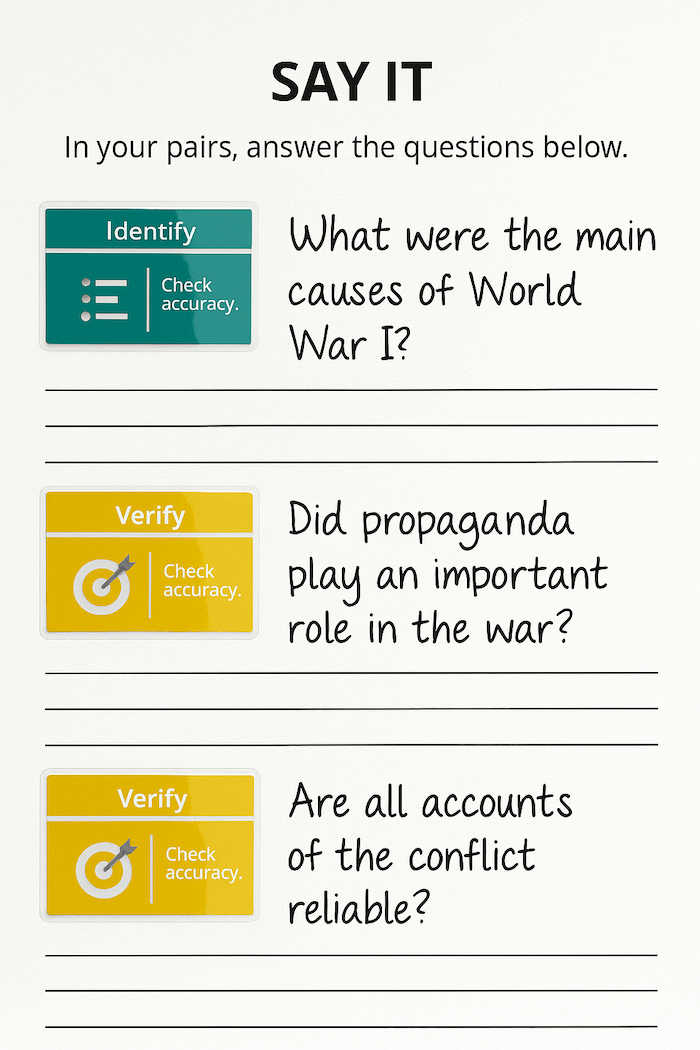

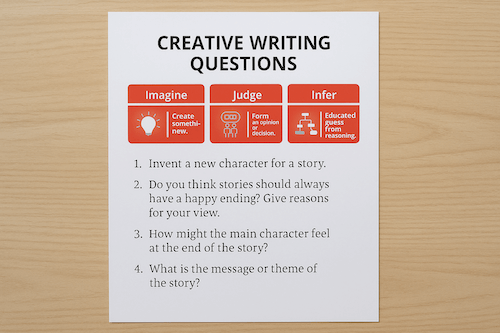

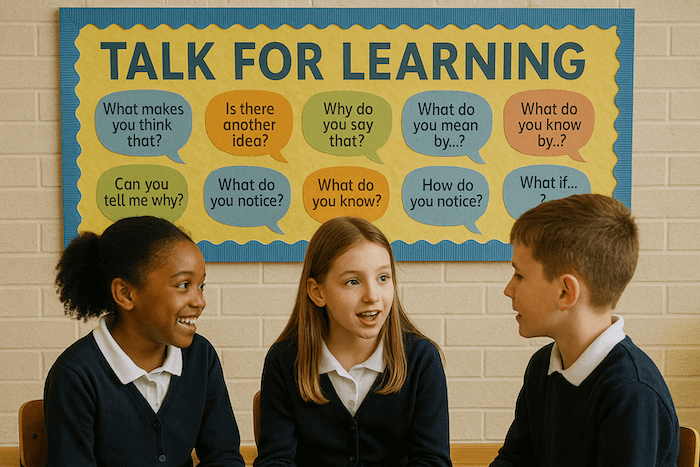

Building a classroom culture of questioning is foundational. Using the Thinking Framework as a guide, teachers can explicitly model how to generate, respond to, and reflect on purposeful questions.

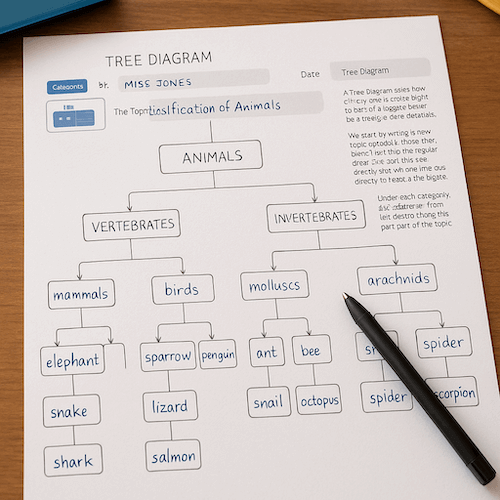

Graphic organizers help learners externalize their thinking, which makes assumptions visible and examinable.

Reflective learning encourages metacognitive awareness - students begin to understand how they think, not just what they think.

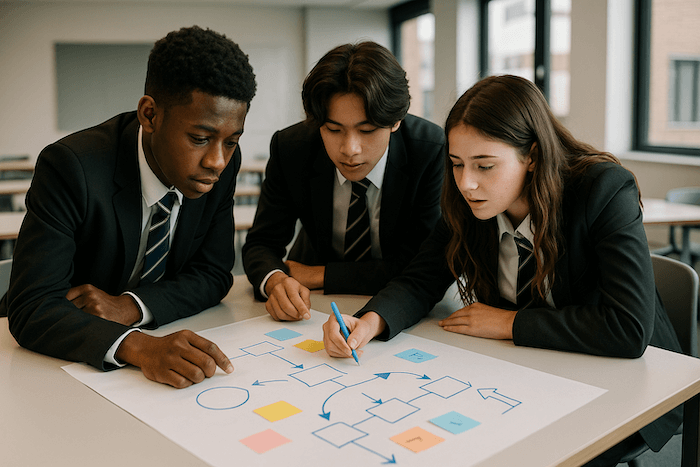

Hands-on, experiential learning is a rich site for developing reasoning and decision-making. With the right tools, these moments can become structured opportunities for higher-order thinking.

A curriculum that nurtures critical thinking doesn’t just cover content—it’s built to deepen thinking. The goal is not to bolt on a few “challenge” tasks, but to design learning journeys that routinely ask students to connect, compare, reason, and refine their ideas. This shift requires intent, structure, and language.

We often work with schools to use the Thinking Framework as a tool for scoping and planning. It helps teaching teams pinpoint what type of thinking is expected at each phase of a learning sequence. Are students expected to identify? To judge? To create? Being explicit about these learning intentions not only supports progression but also gives clarity to curriculum conversations. When used during planning, the framework provides a shared vocabulary to design more coherent, cognitively rich routes through the curriculum.

True critical thinking doesn’t sit in a single subject silo. It shows up when a student questions a character’s motivation in English, prioritises consequences in geography, or represents an idea visually in art.

Subject departments can use simple tools—like Input-Output Diagrams, Mind Maps, or Venn Diagrams—to draw out reasoning in different forms. A well-designed task in PE might ask learners to compare strategies across sports. A music lesson might use Diamond 9 to rank interpretations of a performance. These activities aren’t peripheral - they are central to building thoughtful learners who can apply ideas flexibly.

Embedding critical thinking across the curriculum requires confident, reflective teaching. CPD sessions that invite staff to collaboratively plan, test, and adapt using the Thinking Framework Matrix are a good place to start. Teachers gain more than strategies—they start to see thinking as something they can plan for, observe, and scaffold.

The aim is not to make every lesson “hard” but to make the thinking visible. When curriculum design starts with cognitive intention - not just content coverage—students get more chances to think purposefully and more deeply.

Assessing critical thinking isn’t about ticking off checklists or drilling for right answers—it’s about observing how students approach complexity, how they work through uncertainty, and how they apply their thinking in real contexts. It’s a skill that grows over time, through repeated opportunities to ask, organise, connect, and reason.

To embed meaningful assessment of critical thinking abilities, teachers need to go beyond surface-level performance. The focus shifts toward cognitive skills, creative thinking, and how well students navigate cognitive biases or engage with historical thinking, mathematical thinking, or everyday problem-solving.

Below are seven practical ways to assess critical thinking—each linked to tools and practices from the Structural Learning toolkit:

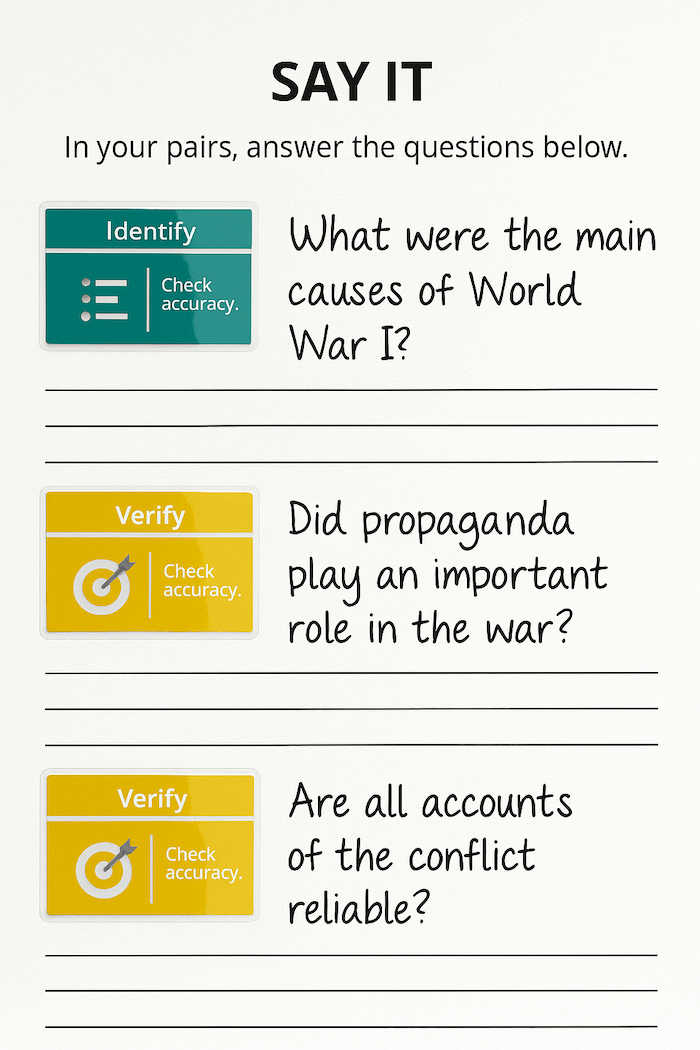

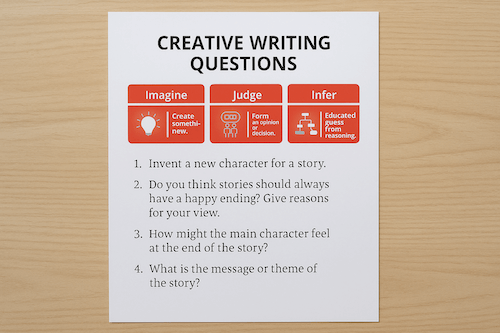

Invite students to generate their own questions using verbs from the Thinking Framework (e.g. compare, categorise, rank). This task reveals how well they understand the underlying structure of a topic. You’ll learn whether they’re working at surface recall or beginning to grapple with nuance and complexity.

Whether it’s a Venn Diagram, Fishbone, or Input-Output Chart, graphic organisers offer visible insight into how students categorise, sequence, or relate ideas. Used midway through a unit, they double up as formative assessment tools - less about "what they know" and more about "how they’re thinking".

When students build out sentences and paragraphs using Writer’s Block, they’re not just improving writing fluency—they’re revealing reasoning. Ask them to construct an argument, explain a historical event, or describe a mathematical process. These hands-on tasks provide a rich source of embedded assessment without breaking the flow of learning.

Give students open-ended, ambiguous tasks that ask for a decision, ranking, or evaluation. For example, use Diamond 9 to rank factors influencing a historical outcome or to evaluate different energy sources in science. Ask them to explain their choices—this verbal or written reasoning offers insight into everyday life decision-making skills.

Regular pause points (e.g. “What changed your mind?” or “What made this hard to explain?”) encourage students to reflect on their thinking. These small windows into metacognition help you assess how aware students are of their biases, strategies, and shifting perspectives.

Use structured activities that require prediction and deduction. For instance, give a partial data set in a maths lesson and ask students to hypothesise the next steps. In history, pose a ‘what if’ question and track how they infer consequences. This develops and assesses mathematical thinking, historical thinking, and reasoning skills in parallel.

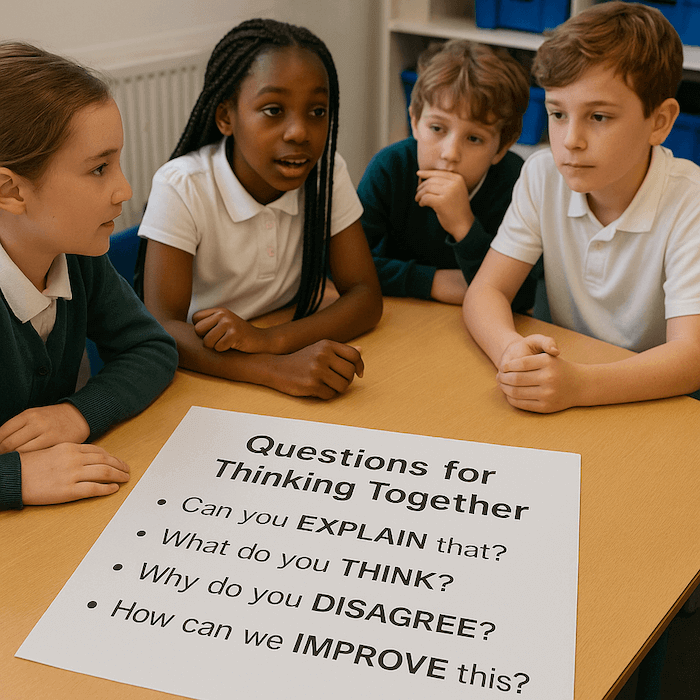

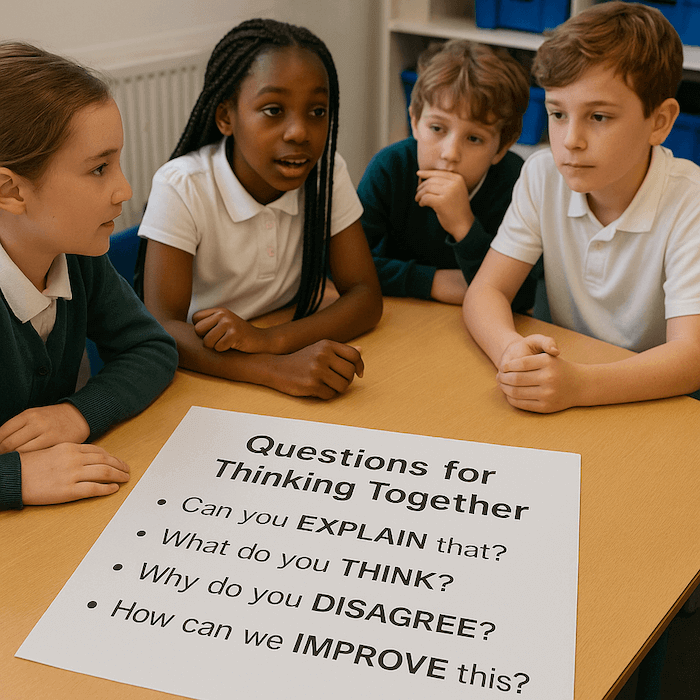

Oral activities such as structured debates, Think-Pair-Share, or Talking Frames allow students to verbalise their ideas before writing. This is especially useful for assessing those who think more fluently aloud. Listen not for correctness, but for the shape of their thinking—how they explore, revise, and connect ideas.

These strategies don’t just assess critical thinking—they actively build it. The key is to create low-stakes, high-cognition tasks that make student thinking visible. Over time, these routines shape learners who are not only better at schoolwork, but better equipped for the real world.

Critical thinking isn’t just something to tick off on a curriculum plan—it’s a habit of mind that stays with learners well beyond the classroom. As the world grows more complex, fast-moving, and noisy, the ability to pause, reflect, and make thoughtful decisions becomes one of the most valuable skills we can offer our students.

When learners are taught to think critically, they’re being trained to ask better questions, sift through information, spot bias, and make reasoned choices. It’s not just about clever problem-solving—although that helps—it’s about equipping them to become flexible thinkers, careful listeners, and confident decision-makers. These are the kinds of skills that transfer across life: into further study, future work, and active citizenship.

This is what a critical thinker can do:

Let’s look at how this shows up in the long term.

Students who think critically aren’t just memorising—they’re constructing understanding. Whether in literature, science, or maths, they’re looking for cause and consequence, weighing up evidence, and making meaningful connections.

This ability supports performance in everything from classroom discussions to written analysis, and shows up even in assessments not explicitly labelled as “critical thinking”. As a result, learners are more likely to retain knowledge, transfer learning between topics, and handle unfamiliar questions with confidence.

Life rarely gives us clear-cut answers. Whether it’s solving a technical problem at work or navigating a personal dilemma, we rely on our ability to reflect, adapt, and think things through. Critical thinking builds the flexibility and resilience students need to meet new challenges with a clear head and an open mind.

Some schools now connect classroom learning with community-based projects, industry challenges, or collaborative problem-solving events. These experiences help students link their learning to real-world complexity—where there are often no neat solutions, just better questions.

In a world overflowing with information, the ability to tell fact from fiction is vital. Critical thinking helps students weigh up sources, question narratives, and explore multiple sides of an issue without falling into polarisation. It empowers them to speak thoughtfully, listen carefully, and engage with nuance.

Ultimately, we want our learners to become thoughtful citizens—people who care about their communities, ask good questions, and contribute ideas that are grounded in both curiosity and evidence.

This is what’s at stake. Not just higher grades. Not just better jobs. But a generation of learners who know how to think for themselves, and for others.

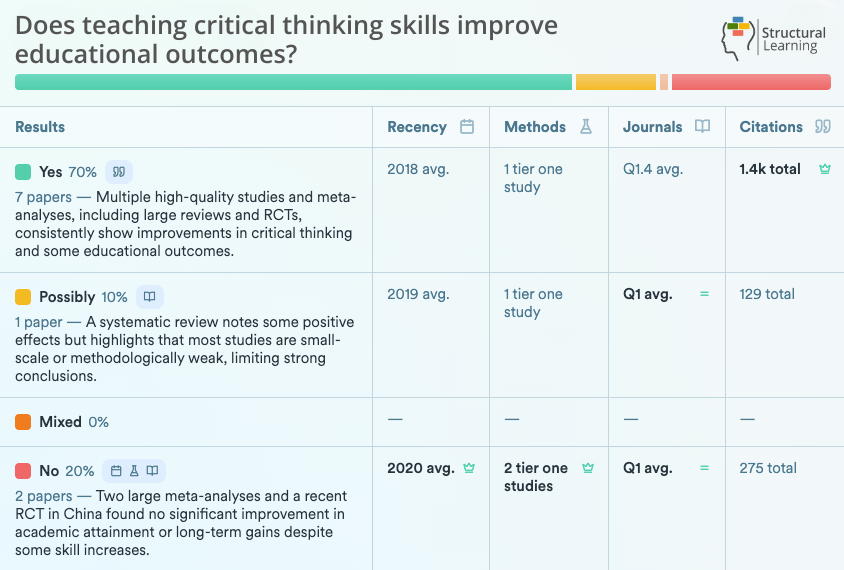

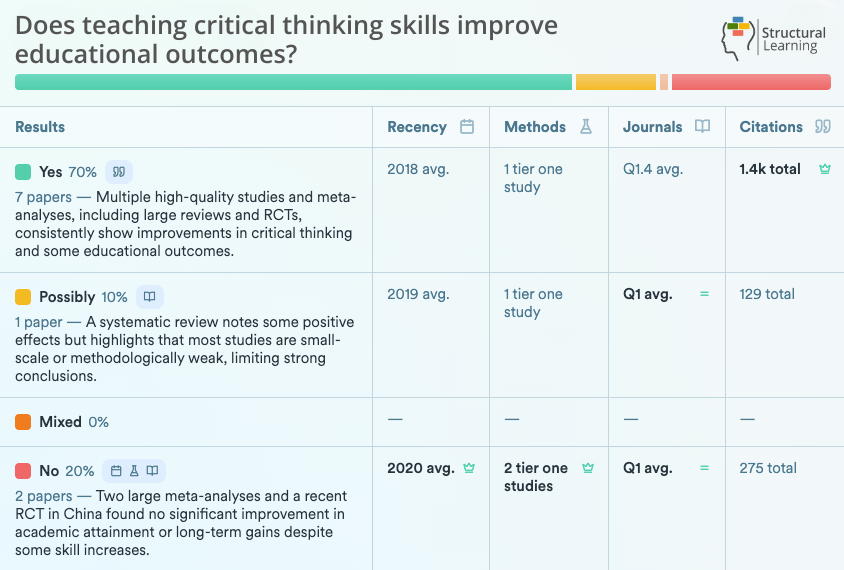

Here are five key studies on critical thinking skills and their impact in the classroom. These studies explore how critical thinking supports the development of informed judgments, effective solutions, and higher-order cognitive processes. They also provide insight into classroom strategies—such as active listening, meaningful discussions, and philosophical thinking—that promote deep engagement with complex ideas and reduce the influence of cognitive biases.

1. Teaching Critical Thinking – Astleitner, H. (2002)

This study highlights how computer-based instruction and multimedia tools support the development of critical thinking skills. Structured approaches improved students' reasoning, helping them form informed judgments and overcome cognitive biases through effective communication and guided analysis.

2. A Path to Critical Thinking – Özkan, İ. (2010)

Classroom activities that included problem-solving, reflection, and questioning significantly boosted learners’ ability to engage with complex ideas. The study supports the value of active listening and meaningful discussions in promoting higher-level cognitive processes.

3. Critical Thinking, Cognitive Psychology of – Halpern, D. (2001)

Halpern outlines how cognitive skill training and metacognitive awareness enhance students’ capacity for skills transfer. The research connects critical thinking with durable cognitive development and improved decision-making in real-world contexts.

4. Critical Thinking Skills in Mathematics – Harish, G. (2012)

This study shows how teaching logic and reasoning in math supports philosophical thinking, allowing students to apply prior knowledge to solve unfamiliar problems. Encouraging reflective habits improved both informed judgments and classroom engagement.

5. Effect of the Using of Think-Pair-Share Learning Model to Critical Thinking Skills – Boleng, D. T. (2016)

Applying the Think-Pair-Share model led to measurable gains in critical thinking skills. Structured peer dialogue enhanced students’ ability to evaluate ideas, discuss effective solutions, and deepen their cognitive process through collaborative inquiry.

Students don’t just take in information - they question it, connect ideas, and explore problems from multiple angles. In a world that demands adaptability and discernment, nurturing critical thinking skills is no longer optional; it’s essential. Yet, for many educators, the challenge isn’t knowing why it matters—it’s knowing how to teach it.

Critical thinking skills are more than a classroom skill. It’s a way of approaching the world with curiosity, care, and logic. It helps learners make sense of conflicting information, ask better questions, and develop reasoned responses. These habits aren’t just useful for exams—they’re vital for real-life decisions and thoughtful participation in society.

This article looks at both the “what” and the “how” of critical thinking. We explore its core components, consider practical strategies for teaching it across subjects, and look at how schools can assess and support its development over time. Whether you’re a teacher, curriculum leader, or simply interested in what good thinking looks like in a modern classroom, this is your starting point for building a culture of reasoning and reflection.

Critical thinking is a structured and rational process for connecting ideas, evaluating evidence, and forming sound, objective judgments. It requires going beyond surface-level understanding and instead analyzing information carefully to make well-informed decisions.

At its core, critical thinking is thinking about our own thinking. It helps us recognize flaws in reasoning, question assumptions, and remain aware of our own cognitive biases. This reflective skill is essential in many fields because it supports ethical, informed decision-making and the ability to generate effective solutions to complex ideas.

Key components of critical thinking include:

To begin developing stronger critical thinking skills, consider the following habits:

Ultimately, critical thinking is more than just a skill—it’s a disciplined cognitive process. It enables us to navigate challenges thoughtfully, engage in meaningful discussions, and respond with clarity, confidence, and ethical awareness.

Critical thinking sits at the heart of meaningful learning. It moves students beyond memorising content and into the realm of deeper understanding, where they explore ideas, make connections, and construct their own insights. In education, this isn’t just an ideal—it’s a necessity.

As classrooms evolve to meet the demands of an increasingly complex world, critical thinking offers a bridge between academic learning and real-world application. It empowers learners to evaluate information, weigh up evidence, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions. These are the habits that support independent learning, thoughtful communication, and informed decision-making.

At Structural Learning, we’re committed to embedding this kind of thinking into everyday classroom life. That means designing routines, visual tools, and physical resources that help make critical thinking visible, teachable, and sustainable. Our aim is not to bolt on thinking skills as an extra—it’s to make them part of the fabric of how learning happens.

The benefits extend far beyond the school gates. Employers consistently rank critical thinking as one of the most sought-after attributes in new hires—valuing it even above subject-specific knowledge. It underpins innovation, adaptability, and the capacity to solve problems in unfamiliar situations.

Put simply, the ability to think critically is one of the most important outcomes of education. It enables learners not only to succeed in the classroom—but to thrive beyond it.

Critical thinking is not a single skill—it’s a constellation of interrelated habits and processes that guide how we handle information, solve problems, and reach conclusions. We see these components as building blocks of deeper learning. By understanding and developing these elements, educators can help students engage with ideas more deliberately, make sound judgments, and approach problems with greater confidence.

Below are four essential components that underpin effective critical thinking in the classroom.

Being open-minded means considering different perspectives without rushing to judgment. It involves challenging assumptions, resisting snap decisions, and staying receptive to new evidence. This kind of flexibility is vital for problem-solving and empathy, especially in classroom discussions where diverse opinions emerge.

How to encourage it: Model curiosity, invite disagreement, and create routines that welcome multiple viewpoints.

Curiosity drives inquiry. It's the engine that keeps learners exploring topics more deeply, asking questions not just to get answers, but to understand the bigger picture. In critical thinking, curiosity pushes students to test their ideas, investigate contradictions, and pursue meaningful insights.

In practice: Encourage students to generate their own questions and reward thoughtful exploration over quick answers.

Analytical thinking helps students examine ideas, spot connections, and evaluate evidence. It’s what allows them to move from surface-level understanding to deeper insight. Rather than accept information at face value, analytical thinkers break problems into parts and examine how those parts relate.

In action: Use tasks that involve comparing sources, identifying patterns, or weighing pros and cons.

Problem-solving transforms thinking into doing. It involves identifying issues, developing possible solutions, and refining those ideas through testing and feedback. Critical thinkers don’t just find answers—they explore alternatives and adjust their thinking when needed.

Support it by: Framing classroom tasks as challenges with more than one right answer. Offer time to explore, revise, and share strategies.

Promoting critical thinking isn't about adding extra content to an already busy timetable—it's about reshaping how students engage with learning. At Structural Learning, we help schools build a culture where thinking is visible, purposeful, and embedded in everyday classroom practice. Using tools such as the Thinking Framework, Writer’s Block, and visual scaffolds like graphic organizers, teachers can equip learners with practical ways to question, reflect, and reason—across every subject.

Here are some grounded, subject-specific strategies that make critical thinking not just teachable, but tangible.

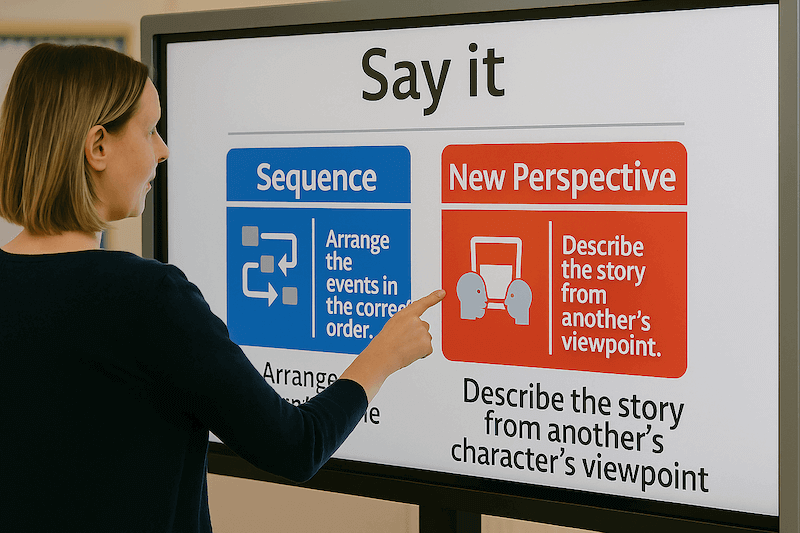

Building a classroom culture of questioning is foundational. Using the Thinking Framework as a guide, teachers can explicitly model how to generate, respond to, and reflect on purposeful questions.

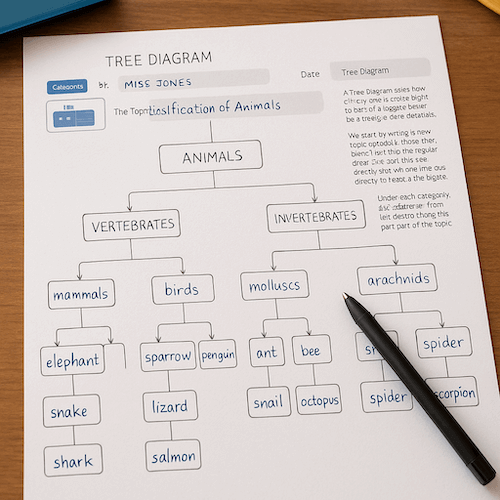

Graphic organizers help learners externalize their thinking, which makes assumptions visible and examinable.

Reflective learning encourages metacognitive awareness - students begin to understand how they think, not just what they think.

Hands-on, experiential learning is a rich site for developing reasoning and decision-making. With the right tools, these moments can become structured opportunities for higher-order thinking.

A curriculum that nurtures critical thinking doesn’t just cover content—it’s built to deepen thinking. The goal is not to bolt on a few “challenge” tasks, but to design learning journeys that routinely ask students to connect, compare, reason, and refine their ideas. This shift requires intent, structure, and language.

We often work with schools to use the Thinking Framework as a tool for scoping and planning. It helps teaching teams pinpoint what type of thinking is expected at each phase of a learning sequence. Are students expected to identify? To judge? To create? Being explicit about these learning intentions not only supports progression but also gives clarity to curriculum conversations. When used during planning, the framework provides a shared vocabulary to design more coherent, cognitively rich routes through the curriculum.

True critical thinking doesn’t sit in a single subject silo. It shows up when a student questions a character’s motivation in English, prioritises consequences in geography, or represents an idea visually in art.

Subject departments can use simple tools—like Input-Output Diagrams, Mind Maps, or Venn Diagrams—to draw out reasoning in different forms. A well-designed task in PE might ask learners to compare strategies across sports. A music lesson might use Diamond 9 to rank interpretations of a performance. These activities aren’t peripheral - they are central to building thoughtful learners who can apply ideas flexibly.

Embedding critical thinking across the curriculum requires confident, reflective teaching. CPD sessions that invite staff to collaboratively plan, test, and adapt using the Thinking Framework Matrix are a good place to start. Teachers gain more than strategies—they start to see thinking as something they can plan for, observe, and scaffold.

The aim is not to make every lesson “hard” but to make the thinking visible. When curriculum design starts with cognitive intention - not just content coverage—students get more chances to think purposefully and more deeply.

Assessing critical thinking isn’t about ticking off checklists or drilling for right answers—it’s about observing how students approach complexity, how they work through uncertainty, and how they apply their thinking in real contexts. It’s a skill that grows over time, through repeated opportunities to ask, organise, connect, and reason.

To embed meaningful assessment of critical thinking abilities, teachers need to go beyond surface-level performance. The focus shifts toward cognitive skills, creative thinking, and how well students navigate cognitive biases or engage with historical thinking, mathematical thinking, or everyday problem-solving.

Below are seven practical ways to assess critical thinking—each linked to tools and practices from the Structural Learning toolkit:

Invite students to generate their own questions using verbs from the Thinking Framework (e.g. compare, categorise, rank). This task reveals how well they understand the underlying structure of a topic. You’ll learn whether they’re working at surface recall or beginning to grapple with nuance and complexity.

Whether it’s a Venn Diagram, Fishbone, or Input-Output Chart, graphic organisers offer visible insight into how students categorise, sequence, or relate ideas. Used midway through a unit, they double up as formative assessment tools - less about "what they know" and more about "how they’re thinking".

When students build out sentences and paragraphs using Writer’s Block, they’re not just improving writing fluency—they’re revealing reasoning. Ask them to construct an argument, explain a historical event, or describe a mathematical process. These hands-on tasks provide a rich source of embedded assessment without breaking the flow of learning.

Give students open-ended, ambiguous tasks that ask for a decision, ranking, or evaluation. For example, use Diamond 9 to rank factors influencing a historical outcome or to evaluate different energy sources in science. Ask them to explain their choices—this verbal or written reasoning offers insight into everyday life decision-making skills.

Regular pause points (e.g. “What changed your mind?” or “What made this hard to explain?”) encourage students to reflect on their thinking. These small windows into metacognition help you assess how aware students are of their biases, strategies, and shifting perspectives.

Use structured activities that require prediction and deduction. For instance, give a partial data set in a maths lesson and ask students to hypothesise the next steps. In history, pose a ‘what if’ question and track how they infer consequences. This develops and assesses mathematical thinking, historical thinking, and reasoning skills in parallel.

Oral activities such as structured debates, Think-Pair-Share, or Talking Frames allow students to verbalise their ideas before writing. This is especially useful for assessing those who think more fluently aloud. Listen not for correctness, but for the shape of their thinking—how they explore, revise, and connect ideas.

These strategies don’t just assess critical thinking—they actively build it. The key is to create low-stakes, high-cognition tasks that make student thinking visible. Over time, these routines shape learners who are not only better at schoolwork, but better equipped for the real world.

Critical thinking isn’t just something to tick off on a curriculum plan—it’s a habit of mind that stays with learners well beyond the classroom. As the world grows more complex, fast-moving, and noisy, the ability to pause, reflect, and make thoughtful decisions becomes one of the most valuable skills we can offer our students.

When learners are taught to think critically, they’re being trained to ask better questions, sift through information, spot bias, and make reasoned choices. It’s not just about clever problem-solving—although that helps—it’s about equipping them to become flexible thinkers, careful listeners, and confident decision-makers. These are the kinds of skills that transfer across life: into further study, future work, and active citizenship.

This is what a critical thinker can do:

Let’s look at how this shows up in the long term.

Students who think critically aren’t just memorising—they’re constructing understanding. Whether in literature, science, or maths, they’re looking for cause and consequence, weighing up evidence, and making meaningful connections.

This ability supports performance in everything from classroom discussions to written analysis, and shows up even in assessments not explicitly labelled as “critical thinking”. As a result, learners are more likely to retain knowledge, transfer learning between topics, and handle unfamiliar questions with confidence.

Life rarely gives us clear-cut answers. Whether it’s solving a technical problem at work or navigating a personal dilemma, we rely on our ability to reflect, adapt, and think things through. Critical thinking builds the flexibility and resilience students need to meet new challenges with a clear head and an open mind.

Some schools now connect classroom learning with community-based projects, industry challenges, or collaborative problem-solving events. These experiences help students link their learning to real-world complexity—where there are often no neat solutions, just better questions.

In a world overflowing with information, the ability to tell fact from fiction is vital. Critical thinking helps students weigh up sources, question narratives, and explore multiple sides of an issue without falling into polarisation. It empowers them to speak thoughtfully, listen carefully, and engage with nuance.

Ultimately, we want our learners to become thoughtful citizens—people who care about their communities, ask good questions, and contribute ideas that are grounded in both curiosity and evidence.

This is what’s at stake. Not just higher grades. Not just better jobs. But a generation of learners who know how to think for themselves, and for others.

Here are five key studies on critical thinking skills and their impact in the classroom. These studies explore how critical thinking supports the development of informed judgments, effective solutions, and higher-order cognitive processes. They also provide insight into classroom strategies—such as active listening, meaningful discussions, and philosophical thinking—that promote deep engagement with complex ideas and reduce the influence of cognitive biases.

1. Teaching Critical Thinking – Astleitner, H. (2002)

This study highlights how computer-based instruction and multimedia tools support the development of critical thinking skills. Structured approaches improved students' reasoning, helping them form informed judgments and overcome cognitive biases through effective communication and guided analysis.

2. A Path to Critical Thinking – Özkan, İ. (2010)

Classroom activities that included problem-solving, reflection, and questioning significantly boosted learners’ ability to engage with complex ideas. The study supports the value of active listening and meaningful discussions in promoting higher-level cognitive processes.

3. Critical Thinking, Cognitive Psychology of – Halpern, D. (2001)

Halpern outlines how cognitive skill training and metacognitive awareness enhance students’ capacity for skills transfer. The research connects critical thinking with durable cognitive development and improved decision-making in real-world contexts.

4. Critical Thinking Skills in Mathematics – Harish, G. (2012)

This study shows how teaching logic and reasoning in math supports philosophical thinking, allowing students to apply prior knowledge to solve unfamiliar problems. Encouraging reflective habits improved both informed judgments and classroom engagement.

5. Effect of the Using of Think-Pair-Share Learning Model to Critical Thinking Skills – Boleng, D. T. (2016)

Applying the Think-Pair-Share model led to measurable gains in critical thinking skills. Structured peer dialogue enhanced students’ ability to evaluate ideas, discuss effective solutions, and deepen their cognitive process through collaborative inquiry.