Ofsted Deep Dives

Ofsted Deep Dives – navigate the inspection process with confidence, showcasing your school's curriculum, teaching methods, and student outcomes.

Ofsted Deep Dives – navigate the inspection process with confidence, showcasing your school's curriculum, teaching methods, and student outcomes.

As school leaders embark on the journey of preparing for Ofsted Deep Dives, it is essential to adopt key strategies that ensure success and demonstrate a thorough understanding of the national curriculum. This process begins with empowering subject leaders, who play a pivotal role in aligning curriculum content with both the school's vision and the requirements set forth by national standards.

By fostering a culture of collaboration and open communication, subject leaders can effectively coordinate with their colleagues to develop a cohesive curriculum that promotes effective learning across all subjects.

One crucial aspect of preparing for Ofsted Deep Dives is to focus on lesson observation, which serves as a window into the instructional practices and learning experiences within the classroom. By engaging in regular, constructive feedback sessions, teachers can refine their pedagogical approaches, ensuring that lessons are not only aligned with the national curriculum but also foster an engaging and supportive learning environment.

Staff meetings provide an excellent opportunity for subject leads to share their expertise, discuss challenges, and collaborate on best practices. Encouraging an ongoing dialogue about teaching strategies and curriculum development enables staff members to stay informed and adapt their methods to better support student learning.

In a secondary school context, it is crucial to consider the unique needs of adolescent learners and tailor the curriculum accordingly, ensuring that the content is both challenging and relevant to students' interests and future aspirations. By anticipating potential deep-dive questions and engaging in self-reflection, schools can proactively address areas for improvement and demonstrate a commitment to continuous growth.

A successful Ofsted Deep Dive preparation relies on effective collaboration among subject leaders, a strong focus on lesson observation, and a well-rounded understanding of the national curriculum. By tapping into resources such as research-based strategies and Ofsted's inspection framework, educators can confidently navigate the inspection process and showcase their dedication to fostering high-quality learning experiences.

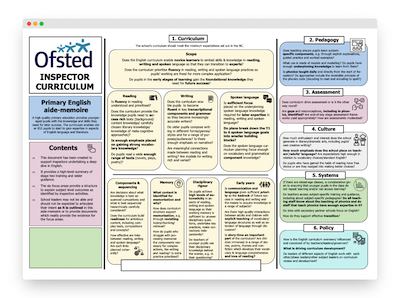

This week (3rd October 2022), the inspection guidance materials from OFSTED were leaked. Originally designed as training materials, the inspection criteria for each subject is quite detailed and this has been summarised into crib sheets for the inspectors. Many school leaders are wondering why they are not given access to a version of this to help them better understand the process in the first place. The documents make interesting reading but shouldn't become the 'way' to run a school. These 'secret sheets' starting with English are summarised below and are intended to be used as a tool to help us think about our curriculum more effectively.

The points below will help your curriculum team think about the quality of education you deliver. If nothing else, it will provide an interesting framework for internal decisions about developing an ambitious curriculum that meets the needs of your current pupils. Explanations of both the primary and secondary education inspection framework are outlined below. It's refreshing to see an inspection methodology from a different perspective; whether you are due a 'visit' or not, these extracts will provide your leadership team with some food for thought.

A high-quality primary education provides younger-aged pupils with the knowledge and skills they need for later success. The curriculum enables older KS2 pupils to start to gain expertise in aspects of English language and literature

Contents and implications for primary school inspectors

Scope

Reading

Writing

Spoken language

Components & sequencing

Memory

Disciplinary rigour

Early years

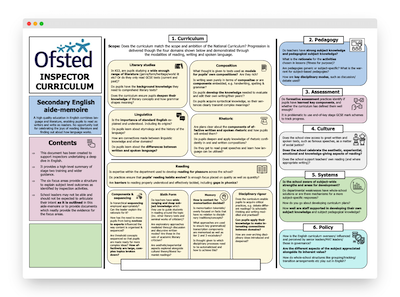

A high-quality education in English combines language and literature, enabling pupils to read as writers and write as readers. No opportunity lost for celebrating the joys of reading literature and finding out about how language works.

Literary studies:

Linguistics:

Composition:

Rhetoric:

Reading:

Components & sequencing:

Sixth Form:

Memory:

Disciplinary rigour:

Automaticity: Ability to recall and deploy (facts, concepts, and methods) with accuracy and speed and without using conscious memory; frees the working memory for higher-order processes that require holding a line of thought. Some transcriptional practices need to be automaticised such as handwriting, capitals and full stops.

Components: The building blocks of knowledge or sub-skills that a pupil needs to understand, store and recall from long-term memory in order to be successful in a complex task. See Automaticity.

Composites: The more complex knowledge which can be acquired or more complex tasks which can be undertaken when prior knowledge components are secure in a pupil’s memory.

Cumulative dysfluency: Educational failure caused when pupils do not have enough opportunities to recall knowledge to gain automaticity with the use of that knowledge. Over time this may cause many gaps in pupils’ knowledge which prevent or limit pupils’ acquisition of more complex knowledge.

Cumulative subjects: These are subjects where there are many possible content choices from which teachers can select e.g. English literature of history. In cumulative subjects, progression over time comes in part from the cumulative addition of more content areas being learned by pupils. The notion of cumulative sufficiency is particularly important when considering curriculum quality in cumulative subjects. Cumulative subjects are usually set in contrast to hierarchical subjects.

Cumulative sufficiency: When the sum totality of curriculum content can be considered an adequate subject education. This notion is particularly useful when considering the quality of the curriculum in subjects where there are many possible content options.

Fluency: Reading with automaticity (rapid word reading without conscious decoding), reading with accuracy (often measured as correct words per minute) and prosody (expressive, phrased reading).

Deep structure (will include subject-specific examples): The different ways a principle can be applied that transcend specific examples. When a principle is first learned, it is used inflexibly as the learner will tie that knowledge to the particulars of the context in which the principle has been learned (the ‘surface structure’). As a learner gains expertise through familiarity with the principle and its applications, their knowledge is no longer organised around surface forms, but rather around deep structure. This means that experts can see how the deep structure applies to specific examples and that is an important goal of education.

Disciplinary knowledge: Methods and conceptual frameworks used by specialists in a given subject, e.g. knowledge of history or geography as a discipline.

Expressive language: Refers to how your child uses words to express himself/herself.

Hierarchical subjects: Subjects where content has a clear hierarchical structure and there is often less debate about content choices than for cumulative subjects. This is because there are core components of knowledge that you must know in order to be able to progress within the subject. It would be hard to argue for a mathematics curriculum that didn’t include algebra or place value.

English is both hierarchical and cumulative (non-linear).

Long-term memory: Where knowledge is stored in integrated schema, ready for connecting to and for use without taking up working memory. See schema.

Phonics: The study of the relationship between the spoken and written language. Each letter or combination of letters represent a sound or sounds. The information is codified, as we must be able to recognise which symbols represent which sounds in order to read the language.

Progression model: The planned path from the pupil’s current state of competence to the school’s intended manifestation of expertise.

Schema/schemata (plural): A mental structure of preconceived ideas that organises categories of information and the connections between them.

Substantive knowledge: Subject knowledge (SK); often carries considerable weight in a given subject domain, such as significant concepts.

Understanding: We are using the cognitivist model in which understanding describes pupils’ interconnected knowledge e.g. of facts, concepts and procedures in maths. Understanding describes a certain schematic pattern of knowledge and is not qualitatively different from knowledge. Mental schemata can be viewed as network node diagrams, where nodes represent knowledge (facts, concepts, processes, features) and arcs the relationships between them.

Understanding in this model is a function of the quantity of appropriate nodes and the quantity of appropriate arcs - more knowledge, and more connections between them leads to more understanding. A knowledge schema can always be developed further and this is synonymous with deepening understanding. In this sense a curriculum plan articulates the degree of understanding intended.

In everyday life, the question ‘do you understand?’ invites a binary yes/no response. This implies that understanding is something that is finite and can be possessed absolutely. This is incorrect and leads us into many traps, such as trying to ‘teach for understanding’ as an absolute when understanding can be viewed as a continuum and the nature and degree of understanding sought should be part of a teacher’s articulated curricular intent.

Working (short-term) memory: Where conscious processing or ‘thoughts’ occur. Limited to holding four to seven items of information for up to around 30 seconds at a time.

As school leaders embark on the journey of preparing for Ofsted Deep Dives, it is essential to adopt key strategies that ensure success and demonstrate a thorough understanding of the national curriculum. This process begins with empowering subject leaders, who play a pivotal role in aligning curriculum content with both the school's vision and the requirements set forth by national standards.

By fostering a culture of collaboration and open communication, subject leaders can effectively coordinate with their colleagues to develop a cohesive curriculum that promotes effective learning across all subjects.

One crucial aspect of preparing for Ofsted Deep Dives is to focus on lesson observation, which serves as a window into the instructional practices and learning experiences within the classroom. By engaging in regular, constructive feedback sessions, teachers can refine their pedagogical approaches, ensuring that lessons are not only aligned with the national curriculum but also foster an engaging and supportive learning environment.

Staff meetings provide an excellent opportunity for subject leads to share their expertise, discuss challenges, and collaborate on best practices. Encouraging an ongoing dialogue about teaching strategies and curriculum development enables staff members to stay informed and adapt their methods to better support student learning.

In a secondary school context, it is crucial to consider the unique needs of adolescent learners and tailor the curriculum accordingly, ensuring that the content is both challenging and relevant to students' interests and future aspirations. By anticipating potential deep-dive questions and engaging in self-reflection, schools can proactively address areas for improvement and demonstrate a commitment to continuous growth.

A successful Ofsted Deep Dive preparation relies on effective collaboration among subject leaders, a strong focus on lesson observation, and a well-rounded understanding of the national curriculum. By tapping into resources such as research-based strategies and Ofsted's inspection framework, educators can confidently navigate the inspection process and showcase their dedication to fostering high-quality learning experiences.

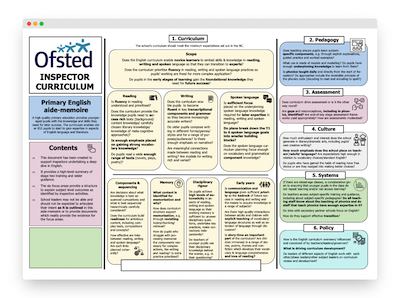

This week (3rd October 2022), the inspection guidance materials from OFSTED were leaked. Originally designed as training materials, the inspection criteria for each subject is quite detailed and this has been summarised into crib sheets for the inspectors. Many school leaders are wondering why they are not given access to a version of this to help them better understand the process in the first place. The documents make interesting reading but shouldn't become the 'way' to run a school. These 'secret sheets' starting with English are summarised below and are intended to be used as a tool to help us think about our curriculum more effectively.

The points below will help your curriculum team think about the quality of education you deliver. If nothing else, it will provide an interesting framework for internal decisions about developing an ambitious curriculum that meets the needs of your current pupils. Explanations of both the primary and secondary education inspection framework are outlined below. It's refreshing to see an inspection methodology from a different perspective; whether you are due a 'visit' or not, these extracts will provide your leadership team with some food for thought.

A high-quality primary education provides younger-aged pupils with the knowledge and skills they need for later success. The curriculum enables older KS2 pupils to start to gain expertise in aspects of English language and literature

Contents and implications for primary school inspectors

Scope

Reading

Writing

Spoken language

Components & sequencing

Memory

Disciplinary rigour

Early years

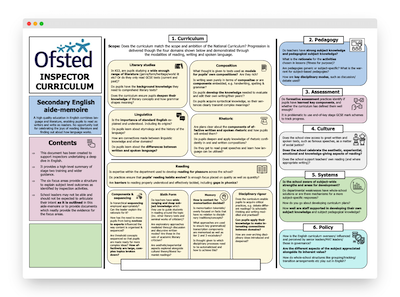

A high-quality education in English combines language and literature, enabling pupils to read as writers and write as readers. No opportunity lost for celebrating the joys of reading literature and finding out about how language works.

Literary studies:

Linguistics:

Composition:

Rhetoric:

Reading:

Components & sequencing:

Sixth Form:

Memory:

Disciplinary rigour:

Automaticity: Ability to recall and deploy (facts, concepts, and methods) with accuracy and speed and without using conscious memory; frees the working memory for higher-order processes that require holding a line of thought. Some transcriptional practices need to be automaticised such as handwriting, capitals and full stops.

Components: The building blocks of knowledge or sub-skills that a pupil needs to understand, store and recall from long-term memory in order to be successful in a complex task. See Automaticity.

Composites: The more complex knowledge which can be acquired or more complex tasks which can be undertaken when prior knowledge components are secure in a pupil’s memory.

Cumulative dysfluency: Educational failure caused when pupils do not have enough opportunities to recall knowledge to gain automaticity with the use of that knowledge. Over time this may cause many gaps in pupils’ knowledge which prevent or limit pupils’ acquisition of more complex knowledge.

Cumulative subjects: These are subjects where there are many possible content choices from which teachers can select e.g. English literature of history. In cumulative subjects, progression over time comes in part from the cumulative addition of more content areas being learned by pupils. The notion of cumulative sufficiency is particularly important when considering curriculum quality in cumulative subjects. Cumulative subjects are usually set in contrast to hierarchical subjects.

Cumulative sufficiency: When the sum totality of curriculum content can be considered an adequate subject education. This notion is particularly useful when considering the quality of the curriculum in subjects where there are many possible content options.

Fluency: Reading with automaticity (rapid word reading without conscious decoding), reading with accuracy (often measured as correct words per minute) and prosody (expressive, phrased reading).

Deep structure (will include subject-specific examples): The different ways a principle can be applied that transcend specific examples. When a principle is first learned, it is used inflexibly as the learner will tie that knowledge to the particulars of the context in which the principle has been learned (the ‘surface structure’). As a learner gains expertise through familiarity with the principle and its applications, their knowledge is no longer organised around surface forms, but rather around deep structure. This means that experts can see how the deep structure applies to specific examples and that is an important goal of education.

Disciplinary knowledge: Methods and conceptual frameworks used by specialists in a given subject, e.g. knowledge of history or geography as a discipline.

Expressive language: Refers to how your child uses words to express himself/herself.

Hierarchical subjects: Subjects where content has a clear hierarchical structure and there is often less debate about content choices than for cumulative subjects. This is because there are core components of knowledge that you must know in order to be able to progress within the subject. It would be hard to argue for a mathematics curriculum that didn’t include algebra or place value.

English is both hierarchical and cumulative (non-linear).

Long-term memory: Where knowledge is stored in integrated schema, ready for connecting to and for use without taking up working memory. See schema.

Phonics: The study of the relationship between the spoken and written language. Each letter or combination of letters represent a sound or sounds. The information is codified, as we must be able to recognise which symbols represent which sounds in order to read the language.

Progression model: The planned path from the pupil’s current state of competence to the school’s intended manifestation of expertise.

Schema/schemata (plural): A mental structure of preconceived ideas that organises categories of information and the connections between them.

Substantive knowledge: Subject knowledge (SK); often carries considerable weight in a given subject domain, such as significant concepts.

Understanding: We are using the cognitivist model in which understanding describes pupils’ interconnected knowledge e.g. of facts, concepts and procedures in maths. Understanding describes a certain schematic pattern of knowledge and is not qualitatively different from knowledge. Mental schemata can be viewed as network node diagrams, where nodes represent knowledge (facts, concepts, processes, features) and arcs the relationships between them.

Understanding in this model is a function of the quantity of appropriate nodes and the quantity of appropriate arcs - more knowledge, and more connections between them leads to more understanding. A knowledge schema can always be developed further and this is synonymous with deepening understanding. In this sense a curriculum plan articulates the degree of understanding intended.

In everyday life, the question ‘do you understand?’ invites a binary yes/no response. This implies that understanding is something that is finite and can be possessed absolutely. This is incorrect and leads us into many traps, such as trying to ‘teach for understanding’ as an absolute when understanding can be viewed as a continuum and the nature and degree of understanding sought should be part of a teacher’s articulated curricular intent.

Working (short-term) memory: Where conscious processing or ‘thoughts’ occur. Limited to holding four to seven items of information for up to around 30 seconds at a time.