Updated on

January 23, 2026

Embracing the Learning Theory: Constructivism

|

August 16, 2021

Discover what constructivist learning theory is and explore practical ways teachers can apply it to boost engagement in the classroom.

Updated on

January 23, 2026

|

August 16, 2021

Discover what constructivist learning theory is and explore practical ways teachers can apply it to boost engagement in the classroom.

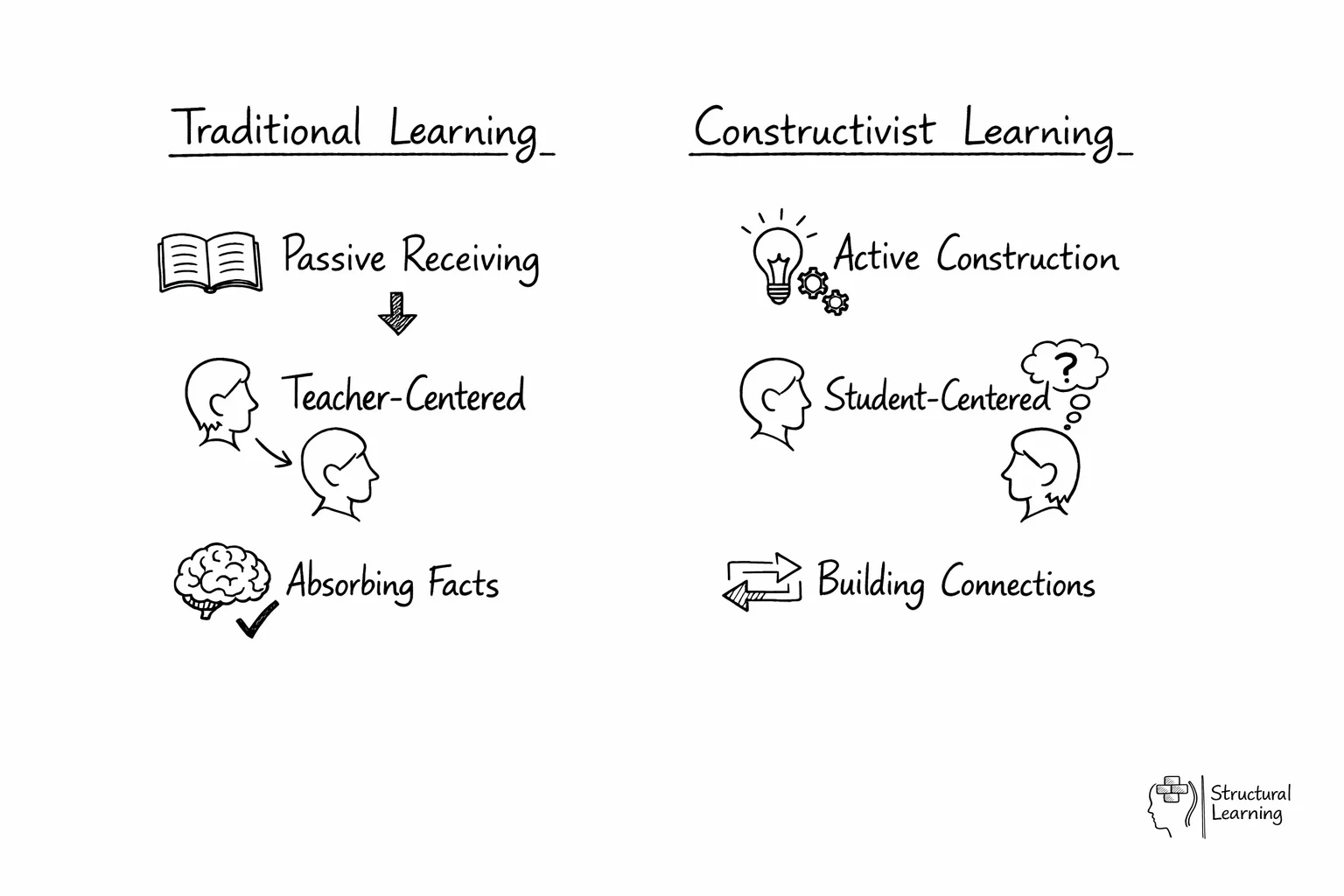

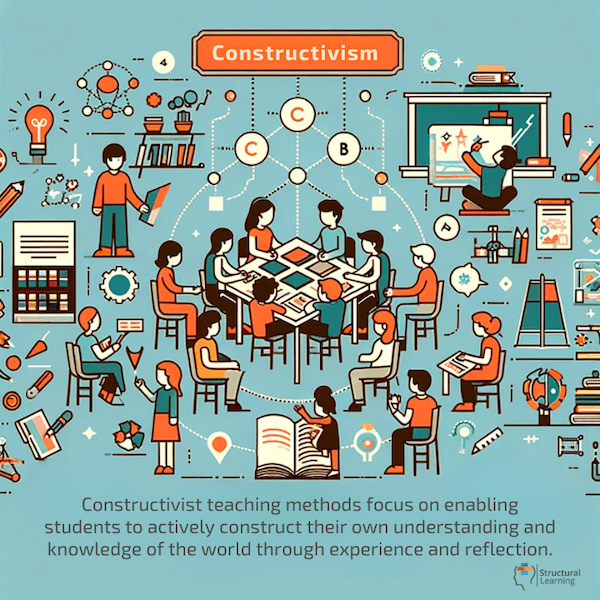

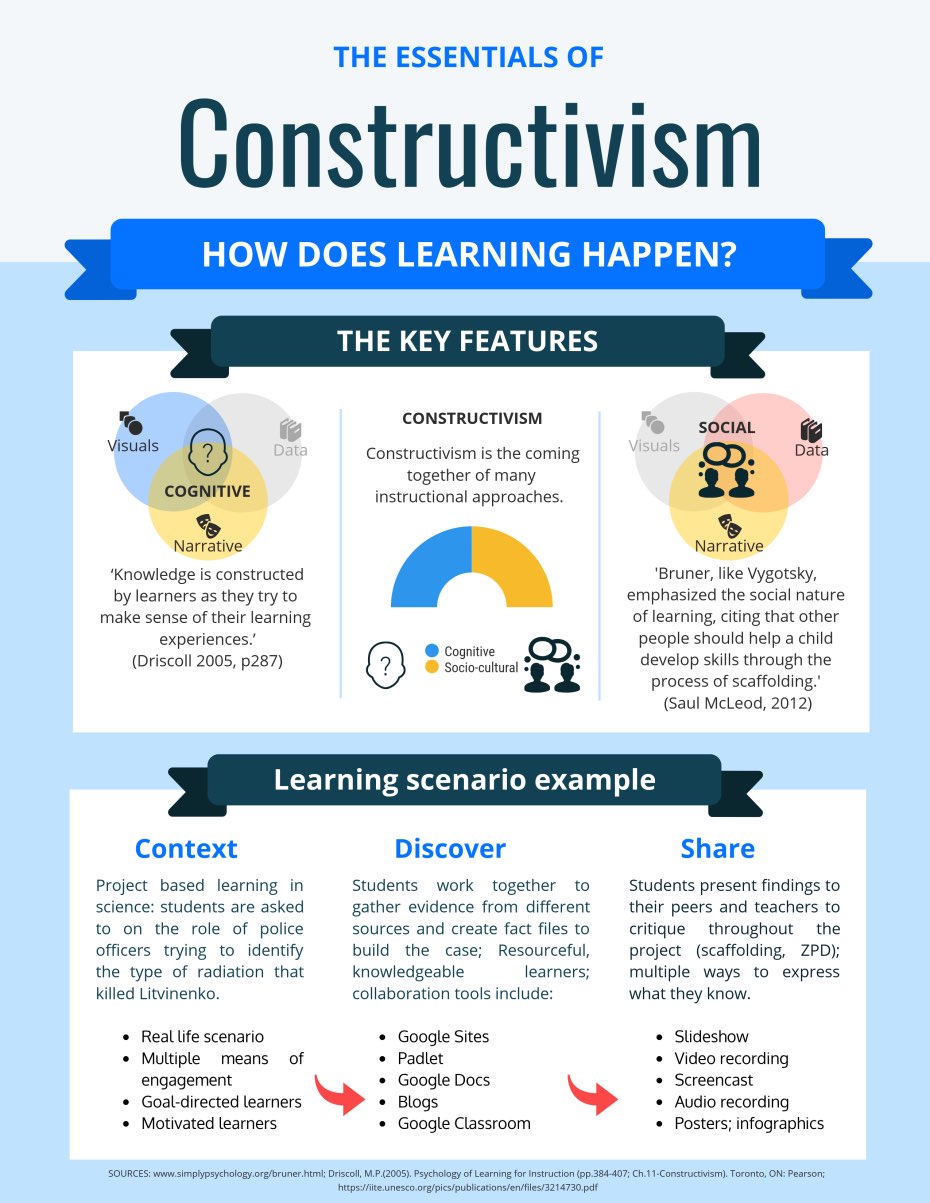

Constructivism is a learning theory in which students actively construct their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information from teachers. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory where learners actively build their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information from teachers. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.

Key principles of constructivist learning include:

In a constructivist classroom, teachers act as facilitators who encourage students to ask questions, investigate, and reflect on their thinking. Lessons move beyond memorisation and focus on applying knowledge to develop reasoning and problem-solving skills. Each learner’s unique experiences are seen as valuable resources that help them build meaningful connections.

If you’re interested in bringing constructivist learning into your teaching practise, consider blending guided inquiry with collaborative projects. These methods help students develop independence, curiosity, and the ability to think critically about the world around them.

Children are free to connect and reconnect the blocks and make as many conceptual connections as they like. The process can be directed as much as the educator likes. At one end of the spectrum, a completely free session would promote discovery learning.

If the material is complex, a more directed approach might be suitable. This approach to learning not only enables an individual learner to understand curriculum material but it also acts as a vehicle for intellectual development. The conversations and reasoning promotes human development.

This approach to promoting critical thinking and communication can be used across subjects and year groups. Whether a learner is in a language class or a maths class, they are engaged in the construction of knowledge. If a child has a lack of background knowledge that other learners within the group can serve as a learning resource.

That is to say, the groups acquisition of knowledge is greater than the sum of its parts. Neil Mercer calls this concept 'Inter-thinking'. Another by product of these social activities is the development of communication skills.

Constructivist theories of learning have increasingly gained attention in the field of education due to its focus on making students active participants in their own learning process. This approach is particularly useful for students with special educational needs who require a more individualized approach to learning. A constructivist approach provides students with an opportunity to learn at their own pace and in a manner that is most conducive to their personal learning styles.

Using inquiry-based learning and learning activities that are designed to be cognitively engaging, students with special educational needs can develop their abilities to process external stimuli in a manner that is most effective for them. A social constructivist model places emphasis on creating a learning environment that is social in nature, providing opportunities for students to collaborate and engage in group work. This approach helps to encourage a sense of community within the classroom, allowing students to learn from each other and to develop a deeper understanding of the concepts being taught.

By embracing a constructivist learning environment, students with special educational needs can make significant strides in their educational growth. This approach allows students to actively engage in the learning process and take ownership of their own learning. As such, this approach is particularly effective for those students who may be struggling with traditional educational models. Incorporating constructivist theories into educational theory can be particularly effective in creating a truly inclusive classroom environment.

In a constructivist classroom, teachers act as facilitators and guides rather than information deliverers, asking probing questions that encourage deeper thinking and providing scaffolding when students struggle. They create learning environments rich with materials and opportunities for exploration while observing student thinking to provide timely support. The teacher's primary responsibility shifts from lecturing to designing experiences that promote discovery and monitoring progress through observation and dialogue.

The primary role of a teacher is to build a collaborative problem-solving environment in which learners show active participation in their learning process. From this viewpoint, an educator acts as a facilitator of learning instead of a teacher. The educator ensures he/she knows about the students' preexisting knowledge, and plans the teaching to apply this knowledge and then build on it.

Scaffolding is a crucial aspect of effective teaching, by which the adult frequently modifies the level of support according to the students' level of performance. In the classroom, scaffolding may include modelling an ability, providing cues or hints, and adapting activity or material.

In a constructivist classroom, the teacher's role is to act as a facilitator or guide rather than a lecturer or dispenser of information. The teacher's primary responsibility is to create a learning environment that encourages students to construct their own knowledge through exploration and inquiry.

This involves providing scaffolding, which can take the form of modelling an ability, providing cues or hints, and adapting activity or material to meet the needs of individual students. T

The teacher also encourages students to collaborate with one another, share their ideas, and reflect on their learning experiences. By doing so, the teacher helps students develop critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Another important role of the teacher in a constructivist classroom is to facilitate the zone of proximal development (ZPD) for each student. This means that the teacher helps students work on tasks that are just beyond their current level of understanding, but still within their reach with guidance and support. By doing so, students are able to stretch their abilities and develop new skills, while feeling challenged and engaged in the learning process. The teacher may use a variety of techniques to facilitate the ZPD, such as scaffolding, modelling, and providing feedback.

Constructivist learning objectives focus on developing critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and the capacity to apply knowledge in novel situations rather than memorizing facts. Students should demonstrate understanding by explaining concepts in their own words, creating original solutions to problems, and connecting new learning to personal experiences. Assessment emphasizes process over product, evaluating how students approach problems and justify their reasoning rather than simply checking for correct answers.

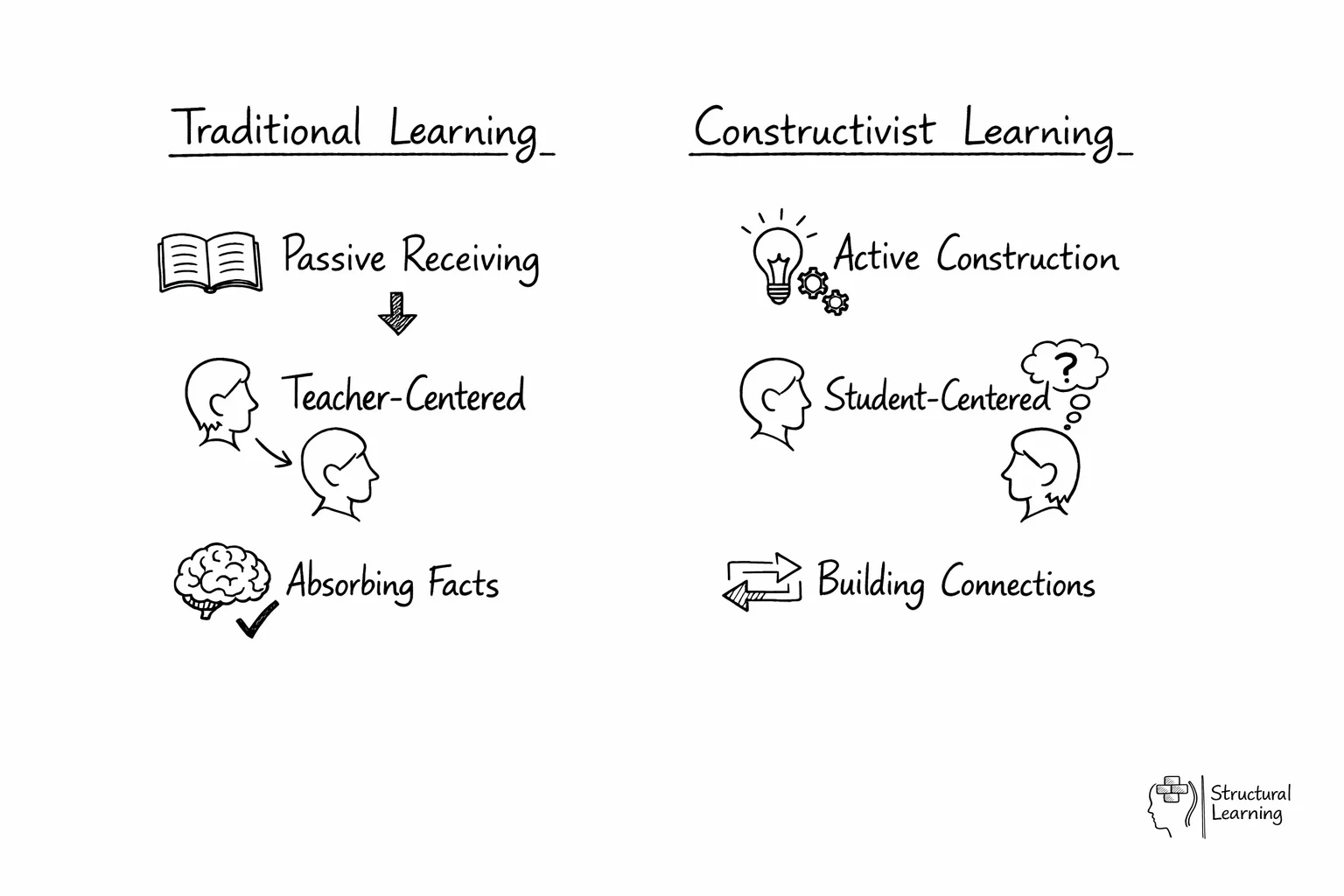

A constructivist classroom is designed to encourage active engagement, exploration, and collaboration, allowing learners to take an active role in knowledge construction. Unlike traditional instruction, where information is transmitted directly from teacher to student, constructivist approaches emphasise learning through experience, reflection, and interaction.

To achieve this, constructivist classrooms focus on six key pedagogical objectives:

Constructivist teaching goes beyond simply presenting information, it encourages students to experience concepts firsthand. This is achieved by:

A core feature of constructivist learning is that students take ownership of their education rather than passively receiving information. This includes:

Learning is not an isolated process, constructivist environments emphasise the importance of dialogue, group work, and shared problem-solving. This is reflected in:

Constructivist teaching recognises that individuals learn in different ways. As such, learning experiences should be varied and dynamic, incorporating:

Constructivist classrooms help students develop awareness of their own thinking processes. This means:

Teachers create constructivist learning environments by arranging flexible seating for collaboration, providing diverse materials for hands-on exploration, and establishing routines that encourage student questioning and investigation. Teachers should create learning centres with manipulatives, technology tools, and resources that support multiple learning styles and allow for different paths to understanding. The physical space and classroom culture must support risk-taking, peer interaction, and student autonomy in learning choices.Setting up a constructivist classroom requires arranging flexible seating for collaboration, providing diverse materials for hands-on exploration, and establishing routines that encourage student questioning and investigation. Teachers should create learning centres with manipulatives, technology tools, and resources that support multiple learning styles and allow for different paths to understanding. The physical space and classroom culture must support risk-taking, peer interaction, and student autonomy in learning choices.

The success of a Constructivist classroom depends upon the following four key areas:

In addition, you might want to think about using a mental representation such as Writer's Block to support the active construction of knowledge.

Constructivist classrooms are usually very different from other types of classrooms. Constructivist classrooms pay attention to students interests and interactive learning. They add to students' pre-existing knowledge and are student-centred. In constructive classrooms, teachers interact with students to guide them to build their knowledge, they encourage negotiation about what students need to achieve success and students mostly work in groups.

Constructivist learning develops deeper understanding and long-term retention because students actively build knowledge through meaningful experiences rather than passive memorization. This approach promotes critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills essential for real-world success while respecting individual learning differences and cultural backgrounds. Students become more engaged and motivated when they have ownership over their learning process and can connect new concepts to their personal experiences.

A constructivist approach to education views learners as active, competent, capable, and powerful. It tends to motivate learners to learn by ‘doing’, which leads to memory retention, critical thinking and engagement. Following are the main benefits of using Constructivism Learning Theory in a classroom.

One of the key figures in the development of constructivism is John Dewey, who believed that education should be centred around the learner and their experiences. Dewey believed that learning should be interactive and that students should be encouraged to explore and discover new information on their own. This approach to education is aligned with constructivism, which emphasizes the active role of the learner in the learning process. By incorporating the principles of constructivism and the ideas of John Dewey into the classroom, educators can create an environment that fosters critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity.

Inquiry-based learning exemplifies constructivist principles by starting with student questions and allowing learners to investigate answers through research, experimentation, and collaboration. Students develop hypotheses, test ideas, and revise understanding based on evidence, mirroring authentic scientific and academic practices. This approach builds both content knowledge and essential skills like questioning, researching, and evaluating information while maintaining high student engagement through ownership of the learning process.

Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) serves as a powerful constructivist teaching technique, drawing inspiration from both Piaget's and Vygotsky's cognitive learning theories. This instructional strategy emphasizes the role of cognitive structures and the knowledge construction process, creating an approach to teaching that fosters active learning and encourages students to take ownership of their educational process.

At the heart of IBL lies the belief that interaction in classroom cultures plays a crucial role in promoting understanding and developing cognitive skills. By engaging students in problem-solving, questioning, and exploration, teachers can create a collaborative environment where the sharing of knowledge happens organically.

This approach not only supports the development of critical thinking skills but also aligns with the cognitive apprenticeship model, in which students learn from their peers and mentors through observation, imitation, and reflection.

Incorporating IBL into classroom practices can significantly enhance the learning experience. By presenting students with real-world problems or open-ended questions, educators can challenge them to actively engage with the subject matter and apply their existing knowledge. This process of discovery and investigation helps students build and refine their cognitive structures, enabling them to construct new knowledge and make meaningful connections to prior experiences.

Ultimately, adopting an inquiry-based approach to teaching can transform the classroom dynamic, turning students from passive recipients of information into active constructors of knowledge. By embracing the principles of constructivism and encouraging a culture of curiosity, educators can help students enable their full potential and cultivate a lifelong love of learning.

Critics argue that pure constructivism can lead to inefficient learning when students lack sufficient background knowledge or when discovering basic facts that could be directly taught more quickly. Some research suggests that minimal guidance during complex problem-solving can overwhelm working memory and actually hinder learning, particularly for novice learners. Additional concerns include difficulty in standardized assessment, potential for misconceptions to persist without correction, and challenges in covering required curriculum content within time constraints.

The Constructivist Learning Theory is mainly criticised for its lack of structure. An individual learner might need highly organised and structured learning environments to prosper, and constructivist learning is mostly related to a more laid-back strategy to help students engage in their learning.

Constructivist classrooms place more value on student progress, rather than grading which may result in students falling behind and without standardized grading it becomes difficult for the teachers to know which students are struggling.

One common criticism of the constructivist learning theory is that it lacks clear instructional strategies for teachers to follow. Without a set curriculum or standardized grading system, some argue that teachers may struggle to guide students towards specific learning goals.

Additionally, some critics argue that constructivism may not be the most effective approach for all types of learners, particularly those who thrive in more structured environments. Despite these criticisms, many educators continue to embrace constructivism as a valuable approach to learning that prioritizes student engagement and critical thinking skills.

Another criticism of the constructivism learning theory is that it may not be suitable for learners at different developmental levels. For example, younger students may not have the cognitive abilities to construct their own knowledge and may need more guidance and structure in their learning.

Similarly, learners with learning disabilities or cognitive delays may struggle with the open-ended nature of constructivism. It's important for educators to consider the individual needs and abilities of their students when implementing any learning theory, including constructivism.

Another criticism of the constructivism learning theory is its emphasis on intellectual development over other forms of development, such as social and emotional development. While constructivism can be effective in promoting critical thinking and problem-solving skills, it may not address the comprehensive needs of the learner. Educators must balance the benefits of constructivism with the importance of addressing all aspects of a student's development.

Research evidence demonstrates that constructivist theory effectively improves learning outcomes, with studies by Piaget, Vygotsky, and Hattie providing empirical support for active knowledge construction and social scaffolding approaches. Modern research by John Hattie shows that constructivist approaches like problem-based learning have moderate to high effect sizes when properly implemented with appropriate teacher guidance. Studies by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) provide important evidence about when and how constructivist methods are most effective, particularly emphasising the need for structured support.Foundational studies include Piaget's research on cognitive development stages showing how children actively construct knowledge through interaction with their environment, and Vygotsky's work on the Zone of Proximal Development demonstrating the importance of social scaffolding. Modern research by John Hattie shows that constructivist approaches like problem-based learning have moderate to high effect sizes when properly implemented with appropriate teacher guidance. Studies by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) provide important evidence about when and how constructivist methods are most effective, particularly emphasising the need for structured support.

Here are five key studies on constructivism and its application in classroom learning, incorporating concepts such as proximal development, active role, mental processes, personal experience, social process, knowledge creation, and constructivist framework:

1. Psychology for the Classroom: Constructivism and Social Learning by A. Pritchard & J. Woollard (2010)

Summary: This study discusses the application of constructivist and social learning theories in the classroom, emphasising the active role of students in their learning process and knowledge creation through e-learning and multimedia.

2. Constructivism and Science Performing Skill Among Elementary Students: A Study by Sambit Padhi & P. Dash (2016)

Summary: The research demonstrates how a constructivist teaching approach significantly improves elementary students' science performance skills, aligning with the philosophy of education that promotes active learning and mental processes.

3. Constructivist Approaches for Teaching and Learning of Science by S. Yaduvanshi & Sunita Singh (2015)

Summary: This study highlights how constructivist teaching-learning approaches in science classrooms enhance understanding and engagement, promoting critical thinking and reflecting the philosophy of personal experience and social process in knowledge creation.

4. Mengukur Keefektifan Teori Konstruktivisme dalam Pembelajaran by M. A. Saputro & Poetri Leharia Pakpahan (2021)

Summary: This study explores the effectiveness of the constructivist theory in learning at the secondary school level, emphasising its role in developing children's cognitive abilities and understanding within a constructivist framework.

5. Students' Perceptions of Constructivist Learning in a Community College American History II Survey Course by J. Maypole & T. G. Davies (2001)

Summary: The paper presents findings from a study on constructivist learning in an American History II survey course, showing increased critical thinking and cognitive development, thereby illustrating the constructivist framework's impact on students' proximal development.

These studies offer insights into the implementation of constructivism in various educational contexts, highlighting its efficacy in encouraging an active role in learning, enhancing mental processes, and shaping personal experiences as part of the social process of knowledge creation.

Students, educators, and parents frequently ask questions about constructivism's practical implementation, its effectiveness compared to traditional teaching methods, and how to create constructivist learning environments. Unlike traditional methods that focus on information transfer from teacher to student, constructivism positions learners at the centre of the process, connecting new ideas with their existing knowledge and experiences.Constructivism is a learning theory where students actively build knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively absorbing facts. Unlike traditional methods that focus on information transfer from teacher to student, constructivism positions learners at the centre of the process, connecting new ideas with their existing knowledge and experiences.

Teachers should blend guided inquiry with collaborative projects, acting as facilitators who provide strategic guidance rather than leaving students in unstructured free play. This involves using authentic formative assessment to understand where students are in their learning and adapting instruction accordingly, ensuring exploration remains both meaningful and goal-oriented.

Prior knowledge serves as a foundation upon which all new learning is built, as students interpret new information through their existing experiences and understanding. Teachers should identify students' prior knowledge before introducing new concepts and help them make meaningful connections between old and new ideas to enhance comprehension.

Social interaction deepens learning through dialogue, collaboration, and shared problem-solving, as knowledge is reinforced and refined within a community of learners. However, this requires structured protocols and teacher facilitation through guided discussions, thought-provoking questions, and encouraging students to articulate their reasoning to prevent chaos.

Block-building methodology is highlighted as an effective approach where learners physically construct their understanding by manipulating ideas and making conceptual connections. This hands-on, problem-solving approach allows teachers to assess student thinking in real time whilst providing clear assessment criteria and guidance for purposeful exploration.

The primary challenge is that pure student-led exploration often fails without proper structure, potentially leading to misconceptions or unfocused learning. Teachers can overcome this by striking a balance between student independence and educator guidance, using responsive teaching that observes learner participation and adapts learning experiences accordingly.

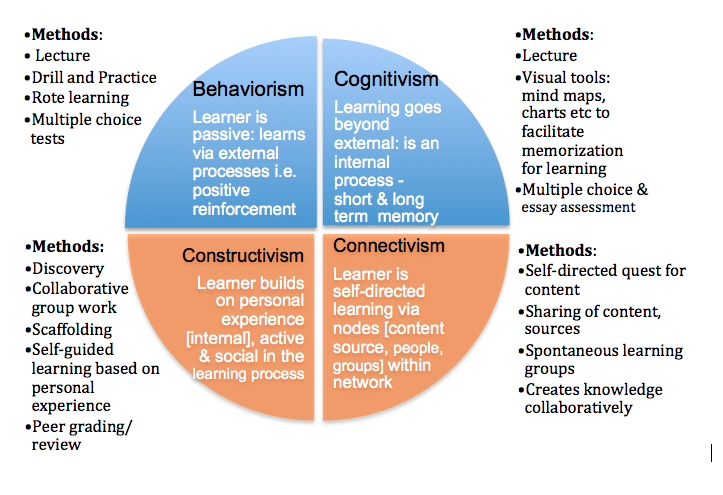

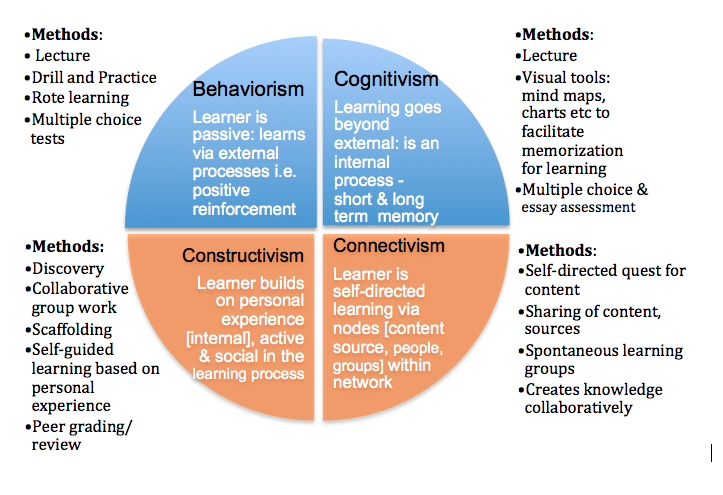

Cognitive constructivism, developed by Piaget, focuses on individual mental processes and how students personally organise information and build schemas. Social constructivism, based on Vygotsky's work, emphasises collaborative learning, cultural context, and the role of social interaction and language in knowledge construction.

These peer-reviewed studies provide the research foundation for the strategies discussed in this article:

Enabling active learning: A social annotation tool for improving student involvement View study ↗

17 citations

Tristan Cui & Jeff Wang (2023)

This study found that when students used a digital tool called Perusall to make notes and comments on reading materials before class, their performance on assessments improved significantly. The research demonstrates that encouraging students to actively engage with course materials through collaborative annotation helps them construct deeper understanding and retain knowledge better. Teachers can use this finding to justify incorporating pre-class reading activities that require students to interact with texts rather than passively consume them.

PSYCHOPEDAGOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF INCLUSIVE EDUCATION View study ↗

Milanə Həsənova (2025)

This comprehensive analysis explores how major learning theories, including constructivism, support inclusive classroom practices that accommodate all learners. The research connects Vygotsky's ideas about social learning, Gardner's multiple intelligences, and other foundational theories to show how inclusive education naturally aligns with how students actually learn best. Teachers will find practical connections between educational theory and creating classrooms where every student can build knowledge in ways that work for their individual needs and strengths.

Teacher-informed Expansion of an Idea Detection Model for a Knowledge Integration Assessment View study ↗

3 citations

Weiying Li et al. (2024)

Researchers developed an assessment approach that encourages students to elaborate on their thinking, compare different ideas, and connect their strongest insights in science learning. This constructivist assessment method helps teachers understand not just what students know, but how they think through problems and build on their existing knowledge. The study shows how teachers can move beyond traditional testing to use assessments that actually support student learning while providing valuable information for planning future lessons.

EXPLORING CONSTRUCTIVIST LEARNING THEORY AND ITS APPLICATIONS IN TEACHING ENGLISH View study ↗

17 citations

Farqad Malik Jumaah (2024)

This research demonstrates how constructivist teaching methods, which focus on students actively building their own understanding, can dramatically improve English language learning outcomes. The study shows that when teachers encourage students to reflect on their experiences, engage in problem-solving, and connect new language concepts to what they already know, language acquisition becomes more natural and effective. English teachers will discover practical strategies for creating learner-centred classrooms where students develop both language skills and critical thinking abilities.

Student Independent Self Assessment: Testing the Efficiency of Self Assessment in a Classroom Setting View study ↗

Anya Nehra & J. Leddo (2024)

This study reveals that students can accurately evaluate their own understanding using a method called Cognitive Structure Analysis, which goes beyond simply knowing right answers to assess deep comprehension. The research found that when students self-assess their knowledge structure, they become better problem solvers and more aware of their learning gaps. Teachers can use these findings to help students take ownership of their learning while gaining insights into how well students truly understand concepts rather than just memorize information.

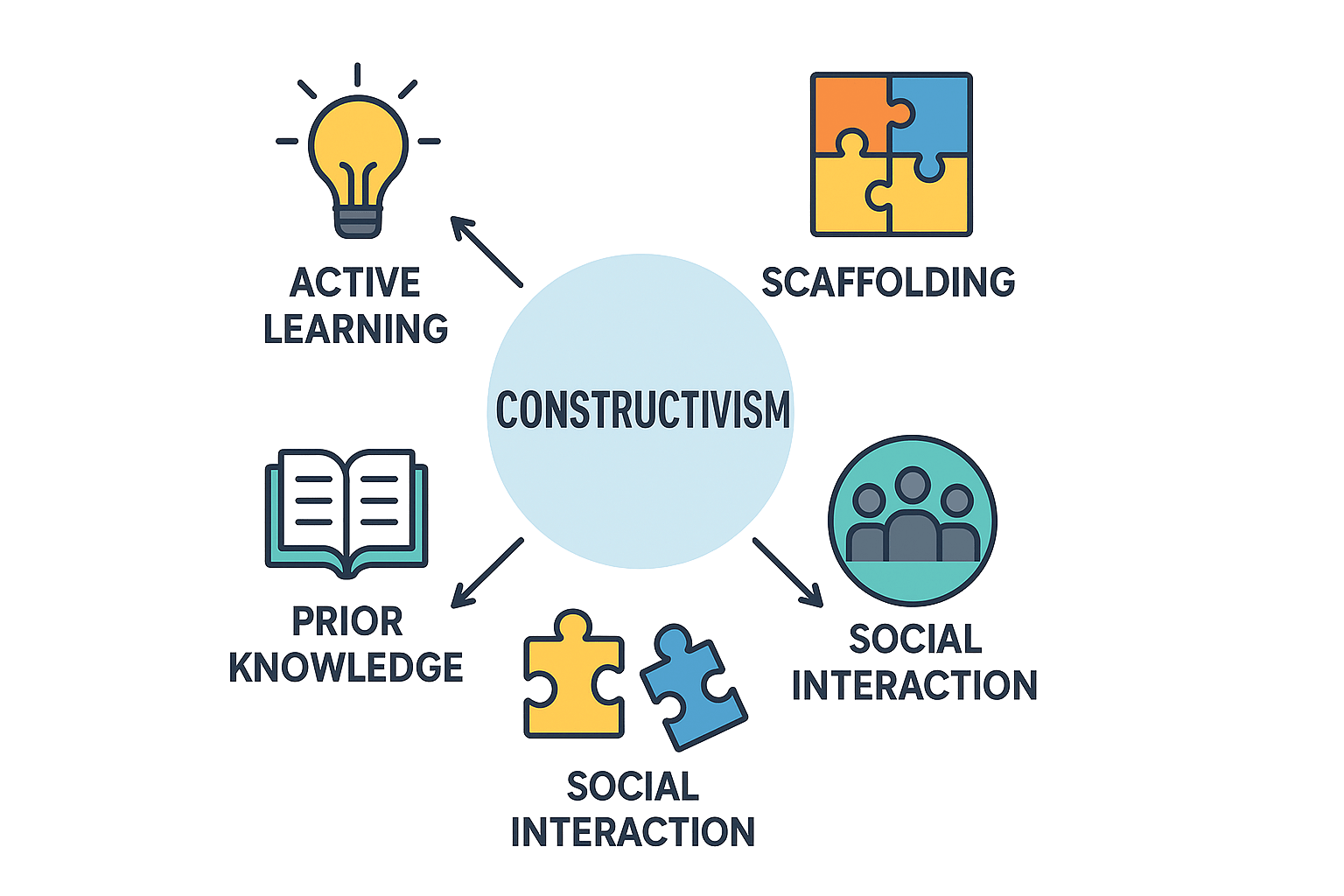

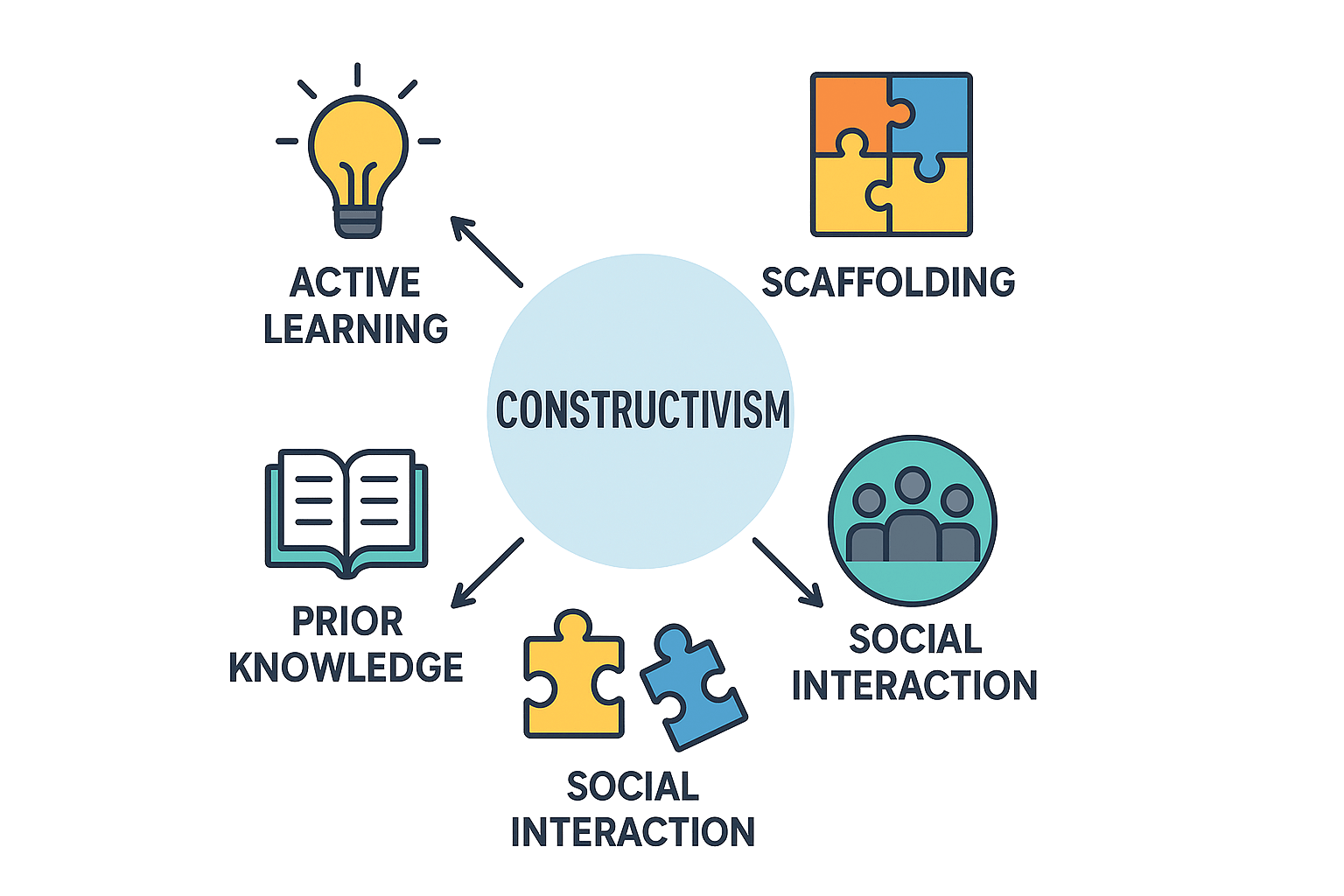

Understanding constructivism's core principles helps teachers create more effective learning environments where students actively build their own understanding. These foundational ideas, developed by theorists including Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, shape how we approach teaching in modern classrooms.

The first principle centres on learning as an active process. Students don't simply receive information; they construct meaning through hands-on exploration and experimentation. In a Year 4 science lesson, rather than telling pupils that plants need light, teachers might have them grow seedlings in different conditions, observing and recording results to build their own conclusions.

The second principle recognises that knowledge builds on existing understanding. Piaget called these mental frameworks 'schemas', which learners constantly update as they encounter new information. When teaching fractions in Year 6, connecting to pupils' experience of sharing pizza or dividing sweets helps them grasp abstract mathematical concepts more readily than starting with numerical symbols alone.

The third principle emphasises social interaction as crucial to learning. Vygotsky's concept of the Zone of Proximal Development suggests students learn best when working with peers or teachers who can support them just beyond their current ability. Structured group work, where pupils explain their thinking to partners or debate different solutions, deepens understanding far more than isolated study.

Finally, authentic contexts enhance learning. When students see real-world applications, they engage more deeply with content. A history teacher might have pupils create museum exhibits about Tudor life, requiring them to research, synthesise information, and present to an audience, rather than simply memorising dates and names.

These principles work together, creating classrooms where students actively participate in their own learning process, building strong understanding that extends beyond test preparation.

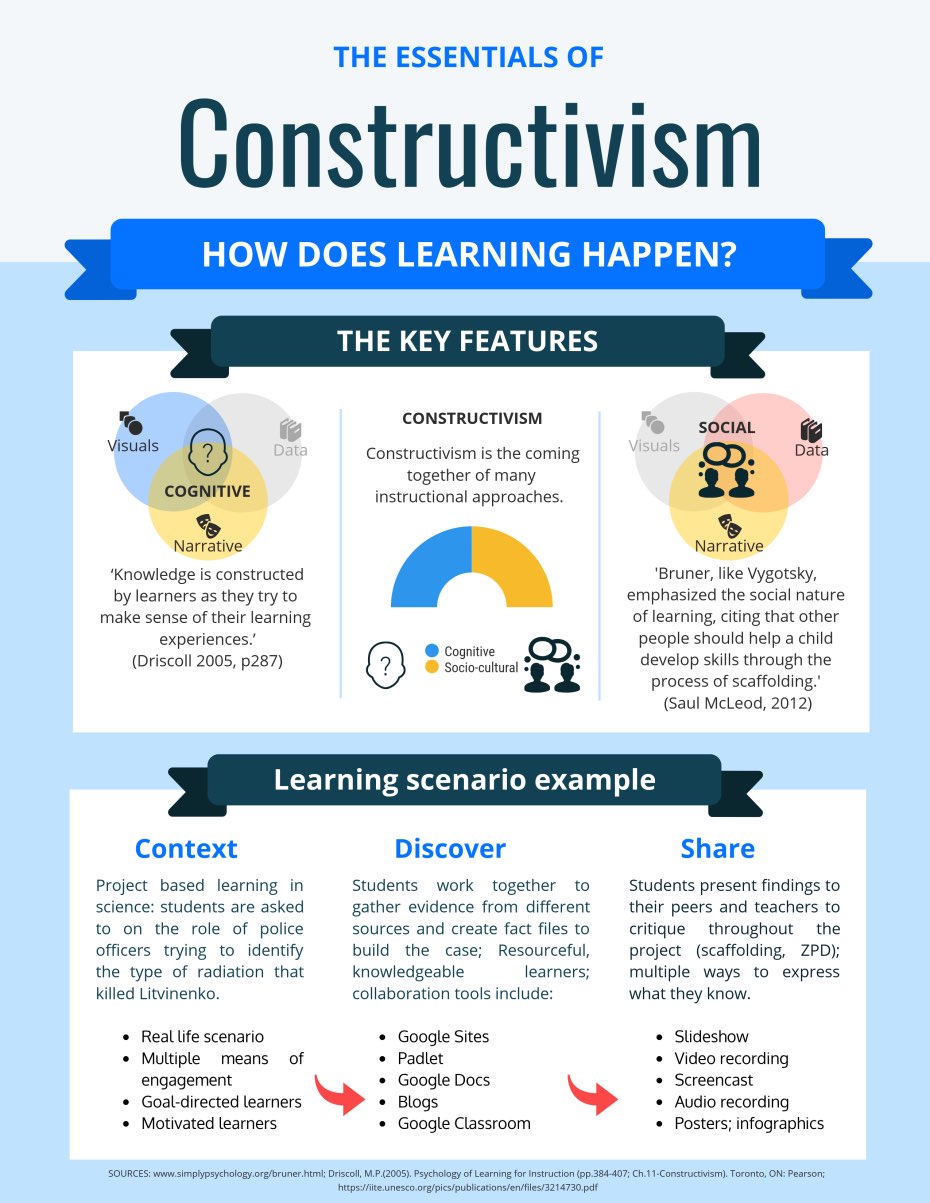

Constructivist learning theory encompasses three primary types: cognitive constructivism, social constructivism, and radical constructivism, each emphasising different aspects of how learners actively build knowledge. Recognising these differences helps teachers select strategies that match their students' needs and learning contexts.Whilst constructivism shares common foundations, educators benefit from understanding its distinct branches, each offering unique approaches to classroom practise. Recognising these differences helps teachers select strategies that match their students' needs and learning contexts.

Cognitive Constructivism, rooted in Piaget's work, focuses on individual mental processes. Students build knowledge through personal discovery and hands-on exploration. In practise, this might involve Year 4 pupils investigating floating and sinking with various objects, recording predictions, then revising their theories based on observations. Teachers provide materials and prompts but allow students to construct their own understanding of density and buoyancy.

Social Constructivism, influenced by Vygotsky, emphasises learning through social interaction and cultural tools. Knowledge develops through dialogue, collaboration, and shared problem-solving. A secondary history teacher might organise debates where students adopt historical perspectives, discussing the Industrial Revolution from workers', factory owners', and reformers' viewpoints. This approach reveals how understanding emerges through exchanging ideas and challenging assumptions.

Radical Constructivism, developed by von Glasersfeld, proposes that knowledge reflects personal experience rather than objective reality. Teachers using this approach might ask students to create multiple valid solutions to open-ended problems. For instance, in a design technology lesson, pupils could develop different approaches to creating earthquake-resistant structures, each reflecting their unique reasoning and experiences.

These types aren't mutually exclusive; effective teachers often blend approaches. A primary maths lesson might begin with individual exploration (cognitive), move to peer discussion (social), then encourage students to explain their unique problem-solving methods (radical). Understanding these distinctions helps educators make informed choices about when to emphasise independent discovery versus collaborative learning, ensuring constructivist principles translate into meaningful classroom experiences.

The fundamental principles of constructivism include active knowledge construction, prior experience integration, social learning through collaboration, and meaningful context-based understanding that learners build rather than passively receive. At its core, constructivism views learners as active builders of knowledge rather than passive recipients, fundamentally changing our approach to teaching.

The first principle recognises that learning is inherently active. Students construct meaning by connecting new information to their existing knowledge framework. In practise, this means moving beyond traditional lecture formats. For instance, when teaching fractions, rather than simply explaining the concept, you might have students physically divide objects into parts, allowing them to discover the relationships themselves whilst you guide their observations.

Social interaction forms the second crucial principle. Vygotsky's research demonstrated that learning occurs most effectively through dialogue and collaboration. This translates directly to classroom practise through structured peer discussions. Try implementing 'think-pair-share' activities where students first reflect independently, then discuss with a partner before sharing with the class. This scaffolded approach ensures all students actively process new concepts.

The third principle acknowledges that context shapes understanding. Learning isn't abstract; it's deeply connected to the situations where it occurs. Practical application might involve teaching measurement through a classroom redesign project, where students calculate areas and volumes for real purposes, making mathematical concepts tangible and memorable.

Finally, constructivism recognises that knowledge building is a gradual, sometimes messy process. Students need time to test ideas, make mistakes, and revise their understanding. This principle encourages teachers to view errors as learning opportunities rather than failures, creating classroom environments where intellectual risk-taking is valued and supported.

Implement constructivist learning in practise by designing student-centred activities that encourage active knowledge construction through hands-on experiences, collaborative problem-solving, and reflective discussion. Rather than abandoning direct instruction entirely, effective constructivist teaching blends guided discovery with structured support to help students build meaningful understanding.

Begin with problem-based scenarios that connect to students' existing experiences. For instance, when teaching fractions in Year 5, present a real pizza-sharing dilemma: "Your group of 8 friends ordered 3 pizzas, but 2 more friends arrived. How can everyone get a fair share?" This approach activates prior knowledge whilst introducing new mathematical concepts through authentic problem-solving.

Implement think-pair-share protocols to structure collaborative learning effectively. Students first tackle problems independently, then discuss solutions with a partner before sharing with the larger group. This progression prevents the chaos of unstructured group work whilst ensuring every learner actively constructs understanding. Research by Johnson and Johnson (2019) demonstrates that structured peer interaction increases conceptual understanding by up to 40% compared to individual work alone.

Create learning stations that allow students to explore concepts through multiple modalities. When teaching electrical circuits, establish hands-on building stations, digital simulation areas, and diagram-drawing spaces. Students rotate through each station, constructing knowledge through varied experiences. This approach accommodates different learning preferences whilst maintaining the active engagement central to constructivist philosophy.

Remember that constructivist teaching doesn't mean stepping back completely. Your role shifts from information deliverer to learning facilitator, providing scaffolding when students struggle and challenging questions when they're ready to extend their thinking. Regular formative assessment through observation and questioning helps you gauge when to intervene and when to allow productive struggle.

Constructivist approaches offer advantages including enhanced critical thinking and student engagement, whilst presenting potential drawbacks such as increased preparation time and assessment difficulties for educators. Understanding both sides helps educators implement this approach effectively whilst avoiding common pitfalls.

Key Advantages: Students develop deeper understanding when they build knowledge actively. Research by Piaget and Vygotsky demonstrates that learners retain concepts better when they construct meaning through experience. In practise, this means Year 8 students exploring fraction concepts through pizza-sharing scenarios remember mathematical principles far longer than those who simply memorise rules. Additionally, constructivist methods naturally develop critical thinking skills; students learn to question, analyse, and evaluate rather than accept information passively.

Notable Challenges: Time constraints pose the most significant barrier. Constructivist activities typically require double the time of traditional instruction, creating pressure when covering extensive curriculum content. Assessment becomes more complex too, as standardised tests rarely measure the deep understanding constructivism develops. Teachers often struggle to evaluate collaborative work fairly or capture learning that emerges through discussion and exploration.

Practical Solutions: Start small by introducing one constructivist activity per week, perhaps a 20-minute problem-solving session where students work in pairs to explain scientific phenomena using everyday materials. Create assessment rubrics that value process alongside product; for instance, photograph students' block constructions at different stages to document their thinking evolution. Consider "hybrid lessons" that blend direct instruction with constructivist exploration, such as introducing key vocabulary traditionally before students investigate word meanings through context and peer discussion.

Success with constructivism requires realistic expectations and gradual implementation. Teachers who acknowledge these challenges whilst embracing the approach's strengths create classrooms where genuine understanding flourishes alongside curriculum coverage.

In constructivist classrooms, teachers shift from being information deliverers to becoming learning facilitators who guide students through their discovery process. This transformation requires specific skills and approaches that many educators find challenging at first, yet research shows it significantly improves active learning and retention.

The teacher's primary responsibility becomes creating environments where students can explore concepts safely whilst providing strategic support. Rather than lecturing, teachers pose thought-provoking questions that challenge assumptions. For instance, when teaching fractions, instead of explaining rules, you might present pizza-sharing scenarios and ask, "How would you divide three pizzas equally amongst four friends?" This approach encourages students to develop their own understanding through practical problem-solving.

Effective constructivist teachers master the art of scaffolding; they provide temporary support structures that students gradually outgrow. This might involve modelling thinking processes aloud, offering sentence starters for group discussions, or providing graphic organisers that help students structure their discoveries. As students gain confidence, these supports are systematically removed.

Assessment also transforms in constructivist settings. Teachers observe student conversations, analyse problem-solving approaches, and review learning journals rather than relying solely on traditional tests. One successful strategy involves "exit tickets" where students write three things they've learnt and one question they still have, providing immediate insight into their understanding.

Perhaps most importantly, constructivist teachers embrace uncertainty. When students propose unexpected solutions or interpretations, skilled facilitators explore these ideas rather than immediately correcting them. This approach, supported by Vygotsky's zone of proximal development theory, recognises that productive struggle leads to deeper understanding than passive reception of correct answers.

Effects of Teachers' Roles as Scaffolding in Classroom Instruction View study ↗

4 citations

Zheren Wang (2024)

This research examines how teachers can effectively support student learning by acting as scaffolds, drawing on Vygotsky's theory that students learn best when guided through their zone of proximal development. The study breaks down different teacher roles and shows through real classroom examples how each approach impacts student understanding. Teachers will find practical insights into when and how to provide the right level of support to help students gradually build independence and deeper learning.

Scaffolding Understanding of Scholarly Educational Research Through Teacher/Student Conferencing and Differentiated Instruction View study ↗

6 citations

G. Ghaith & Ghada M. Awada (2022)

This study found that combining one-on-one teacher conferences with personalised instruction significantly improved graduate students' ability to understand and critically evaluate educational research. The 15-week intervention showed that when teachers tailor their approach to individual student needs and provide direct feedback through conferencing, students develop stronger analytical skills. This approach offers valuable strategies for any educator looking to help students engage more deeply with complex academic material.

Developing and implementing an Einsteinian science curriculum from years 3-10: B. Teacher upskilling: response to training and teacher's classroom experience View study ↗

1 citations

Tejinder Kaur et al. (2024)

This research reveals that successful curriculum innovation depends heavily on comprehensive teacher professional development, particularly when introducing modern physics concepts to younger students. The study tracked how teachers responded to training in Einsteinian physics and implemented these advanced concepts in their classrooms from grades 3-10. Teachers will appreciate the insights into how proper professional development can build confidence and competence when teaching challenging new content that pushes beyond traditional curriculum boundaries.

The The Effect of AI Literacy and Differentiated Instruction on Educational Scaffolding in FEB UNJ View study ↗

Muhamad Al Finsih et al. (2025)

This study explores how teachers' understanding of artificial intelligence combined with differentiated instruction techniques enhances their ability to provide effective educational scaffolding. The research found that when educators are literate in AI tools and skilled in personalising instruction, they create more responsive and supportive learning environments. As AI becomes increasingly present in education, this research offers valuable guidance for teachers looking to integrate technology while maintaining strong pedagogical practices.

Use of Scaffolding Strategies in Teaching and Learning of Mathematics in Class IX: Teachers' and Students' Perceptions View study ↗

Chewang Tenzin Doya (2025)

This study investigated how both teachers and ninth-grade students view scaffolding strategies in mathematics instruction, revealing important insights about implementation challenges and student impact. The research found that while scaffolding within students' zone of proximal development enhances learning, teachers face practical difficulties in consistently applying these individualized support techniques. Mathematics teachers will find this particularly relevant as it addresses real classroom challenges while confirming the value of personalised instructional support.

Constructivism is a learning theory in which students actively construct their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information from teachers. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory where learners actively build their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information from teachers. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct their own knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes learners actively construct knowledge through experience, reflection, and social interaction rather than passively receiving information. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.Constructivism is a learning theory that proposes knowledge is built actively by learners through experience, reflection, and social interaction. Rather than simply absorbing facts, students develop their understanding by connecting new ideas with what they already know. In 2025, constructivist learning theory could be more relevant than ever as educators look to problem-based learning to prepare students for complex, real-world challenges.

Key principles of constructivist learning include:

In a constructivist classroom, teachers act as facilitators who encourage students to ask questions, investigate, and reflect on their thinking. Lessons move beyond memorisation and focus on applying knowledge to develop reasoning and problem-solving skills. Each learner’s unique experiences are seen as valuable resources that help them build meaningful connections.

If you’re interested in bringing constructivist learning into your teaching practise, consider blending guided inquiry with collaborative projects. These methods help students develop independence, curiosity, and the ability to think critically about the world around them.

Children are free to connect and reconnect the blocks and make as many conceptual connections as they like. The process can be directed as much as the educator likes. At one end of the spectrum, a completely free session would promote discovery learning.

If the material is complex, a more directed approach might be suitable. This approach to learning not only enables an individual learner to understand curriculum material but it also acts as a vehicle for intellectual development. The conversations and reasoning promotes human development.

This approach to promoting critical thinking and communication can be used across subjects and year groups. Whether a learner is in a language class or a maths class, they are engaged in the construction of knowledge. If a child has a lack of background knowledge that other learners within the group can serve as a learning resource.

That is to say, the groups acquisition of knowledge is greater than the sum of its parts. Neil Mercer calls this concept 'Inter-thinking'. Another by product of these social activities is the development of communication skills.

Constructivist theories of learning have increasingly gained attention in the field of education due to its focus on making students active participants in their own learning process. This approach is particularly useful for students with special educational needs who require a more individualized approach to learning. A constructivist approach provides students with an opportunity to learn at their own pace and in a manner that is most conducive to their personal learning styles.

Using inquiry-based learning and learning activities that are designed to be cognitively engaging, students with special educational needs can develop their abilities to process external stimuli in a manner that is most effective for them. A social constructivist model places emphasis on creating a learning environment that is social in nature, providing opportunities for students to collaborate and engage in group work. This approach helps to encourage a sense of community within the classroom, allowing students to learn from each other and to develop a deeper understanding of the concepts being taught.

By embracing a constructivist learning environment, students with special educational needs can make significant strides in their educational growth. This approach allows students to actively engage in the learning process and take ownership of their own learning. As such, this approach is particularly effective for those students who may be struggling with traditional educational models. Incorporating constructivist theories into educational theory can be particularly effective in creating a truly inclusive classroom environment.

In a constructivist classroom, teachers act as facilitators and guides rather than information deliverers, asking probing questions that encourage deeper thinking and providing scaffolding when students struggle. They create learning environments rich with materials and opportunities for exploration while observing student thinking to provide timely support. The teacher's primary responsibility shifts from lecturing to designing experiences that promote discovery and monitoring progress through observation and dialogue.

The primary role of a teacher is to build a collaborative problem-solving environment in which learners show active participation in their learning process. From this viewpoint, an educator acts as a facilitator of learning instead of a teacher. The educator ensures he/she knows about the students' preexisting knowledge, and plans the teaching to apply this knowledge and then build on it.

Scaffolding is a crucial aspect of effective teaching, by which the adult frequently modifies the level of support according to the students' level of performance. In the classroom, scaffolding may include modelling an ability, providing cues or hints, and adapting activity or material.

In a constructivist classroom, the teacher's role is to act as a facilitator or guide rather than a lecturer or dispenser of information. The teacher's primary responsibility is to create a learning environment that encourages students to construct their own knowledge through exploration and inquiry.

This involves providing scaffolding, which can take the form of modelling an ability, providing cues or hints, and adapting activity or material to meet the needs of individual students. T

The teacher also encourages students to collaborate with one another, share their ideas, and reflect on their learning experiences. By doing so, the teacher helps students develop critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Another important role of the teacher in a constructivist classroom is to facilitate the zone of proximal development (ZPD) for each student. This means that the teacher helps students work on tasks that are just beyond their current level of understanding, but still within their reach with guidance and support. By doing so, students are able to stretch their abilities and develop new skills, while feeling challenged and engaged in the learning process. The teacher may use a variety of techniques to facilitate the ZPD, such as scaffolding, modelling, and providing feedback.

Constructivist learning objectives focus on developing critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and the capacity to apply knowledge in novel situations rather than memorizing facts. Students should demonstrate understanding by explaining concepts in their own words, creating original solutions to problems, and connecting new learning to personal experiences. Assessment emphasizes process over product, evaluating how students approach problems and justify their reasoning rather than simply checking for correct answers.

A constructivist classroom is designed to encourage active engagement, exploration, and collaboration, allowing learners to take an active role in knowledge construction. Unlike traditional instruction, where information is transmitted directly from teacher to student, constructivist approaches emphasise learning through experience, reflection, and interaction.

To achieve this, constructivist classrooms focus on six key pedagogical objectives:

Constructivist teaching goes beyond simply presenting information, it encourages students to experience concepts firsthand. This is achieved by:

A core feature of constructivist learning is that students take ownership of their education rather than passively receiving information. This includes:

Learning is not an isolated process, constructivist environments emphasise the importance of dialogue, group work, and shared problem-solving. This is reflected in:

Constructivist teaching recognises that individuals learn in different ways. As such, learning experiences should be varied and dynamic, incorporating:

Constructivist classrooms help students develop awareness of their own thinking processes. This means:

Teachers create constructivist learning environments by arranging flexible seating for collaboration, providing diverse materials for hands-on exploration, and establishing routines that encourage student questioning and investigation. Teachers should create learning centres with manipulatives, technology tools, and resources that support multiple learning styles and allow for different paths to understanding. The physical space and classroom culture must support risk-taking, peer interaction, and student autonomy in learning choices.Setting up a constructivist classroom requires arranging flexible seating for collaboration, providing diverse materials for hands-on exploration, and establishing routines that encourage student questioning and investigation. Teachers should create learning centres with manipulatives, technology tools, and resources that support multiple learning styles and allow for different paths to understanding. The physical space and classroom culture must support risk-taking, peer interaction, and student autonomy in learning choices.

The success of a Constructivist classroom depends upon the following four key areas:

In addition, you might want to think about using a mental representation such as Writer's Block to support the active construction of knowledge.

Constructivist classrooms are usually very different from other types of classrooms. Constructivist classrooms pay attention to students interests and interactive learning. They add to students' pre-existing knowledge and are student-centred. In constructive classrooms, teachers interact with students to guide them to build their knowledge, they encourage negotiation about what students need to achieve success and students mostly work in groups.

Constructivist learning develops deeper understanding and long-term retention because students actively build knowledge through meaningful experiences rather than passive memorization. This approach promotes critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills essential for real-world success while respecting individual learning differences and cultural backgrounds. Students become more engaged and motivated when they have ownership over their learning process and can connect new concepts to their personal experiences.

A constructivist approach to education views learners as active, competent, capable, and powerful. It tends to motivate learners to learn by ‘doing’, which leads to memory retention, critical thinking and engagement. Following are the main benefits of using Constructivism Learning Theory in a classroom.

One of the key figures in the development of constructivism is John Dewey, who believed that education should be centred around the learner and their experiences. Dewey believed that learning should be interactive and that students should be encouraged to explore and discover new information on their own. This approach to education is aligned with constructivism, which emphasizes the active role of the learner in the learning process. By incorporating the principles of constructivism and the ideas of John Dewey into the classroom, educators can create an environment that fosters critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity.

Inquiry-based learning exemplifies constructivist principles by starting with student questions and allowing learners to investigate answers through research, experimentation, and collaboration. Students develop hypotheses, test ideas, and revise understanding based on evidence, mirroring authentic scientific and academic practices. This approach builds both content knowledge and essential skills like questioning, researching, and evaluating information while maintaining high student engagement through ownership of the learning process.

Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) serves as a powerful constructivist teaching technique, drawing inspiration from both Piaget's and Vygotsky's cognitive learning theories. This instructional strategy emphasizes the role of cognitive structures and the knowledge construction process, creating an approach to teaching that fosters active learning and encourages students to take ownership of their educational process.

At the heart of IBL lies the belief that interaction in classroom cultures plays a crucial role in promoting understanding and developing cognitive skills. By engaging students in problem-solving, questioning, and exploration, teachers can create a collaborative environment where the sharing of knowledge happens organically.

This approach not only supports the development of critical thinking skills but also aligns with the cognitive apprenticeship model, in which students learn from their peers and mentors through observation, imitation, and reflection.

Incorporating IBL into classroom practices can significantly enhance the learning experience. By presenting students with real-world problems or open-ended questions, educators can challenge them to actively engage with the subject matter and apply their existing knowledge. This process of discovery and investigation helps students build and refine their cognitive structures, enabling them to construct new knowledge and make meaningful connections to prior experiences.

Ultimately, adopting an inquiry-based approach to teaching can transform the classroom dynamic, turning students from passive recipients of information into active constructors of knowledge. By embracing the principles of constructivism and encouraging a culture of curiosity, educators can help students enable their full potential and cultivate a lifelong love of learning.

Critics argue that pure constructivism can lead to inefficient learning when students lack sufficient background knowledge or when discovering basic facts that could be directly taught more quickly. Some research suggests that minimal guidance during complex problem-solving can overwhelm working memory and actually hinder learning, particularly for novice learners. Additional concerns include difficulty in standardized assessment, potential for misconceptions to persist without correction, and challenges in covering required curriculum content within time constraints.

The Constructivist Learning Theory is mainly criticised for its lack of structure. An individual learner might need highly organised and structured learning environments to prosper, and constructivist learning is mostly related to a more laid-back strategy to help students engage in their learning.

Constructivist classrooms place more value on student progress, rather than grading which may result in students falling behind and without standardized grading it becomes difficult for the teachers to know which students are struggling.

One common criticism of the constructivist learning theory is that it lacks clear instructional strategies for teachers to follow. Without a set curriculum or standardized grading system, some argue that teachers may struggle to guide students towards specific learning goals.

Additionally, some critics argue that constructivism may not be the most effective approach for all types of learners, particularly those who thrive in more structured environments. Despite these criticisms, many educators continue to embrace constructivism as a valuable approach to learning that prioritizes student engagement and critical thinking skills.

Another criticism of the constructivism learning theory is that it may not be suitable for learners at different developmental levels. For example, younger students may not have the cognitive abilities to construct their own knowledge and may need more guidance and structure in their learning.

Similarly, learners with learning disabilities or cognitive delays may struggle with the open-ended nature of constructivism. It's important for educators to consider the individual needs and abilities of their students when implementing any learning theory, including constructivism.

Another criticism of the constructivism learning theory is its emphasis on intellectual development over other forms of development, such as social and emotional development. While constructivism can be effective in promoting critical thinking and problem-solving skills, it may not address the comprehensive needs of the learner. Educators must balance the benefits of constructivism with the importance of addressing all aspects of a student's development.

Research evidence demonstrates that constructivist theory effectively improves learning outcomes, with studies by Piaget, Vygotsky, and Hattie providing empirical support for active knowledge construction and social scaffolding approaches. Modern research by John Hattie shows that constructivist approaches like problem-based learning have moderate to high effect sizes when properly implemented with appropriate teacher guidance. Studies by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) provide important evidence about when and how constructivist methods are most effective, particularly emphasising the need for structured support.Foundational studies include Piaget's research on cognitive development stages showing how children actively construct knowledge through interaction with their environment, and Vygotsky's work on the Zone of Proximal Development demonstrating the importance of social scaffolding. Modern research by John Hattie shows that constructivist approaches like problem-based learning have moderate to high effect sizes when properly implemented with appropriate teacher guidance. Studies by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) provide important evidence about when and how constructivist methods are most effective, particularly emphasising the need for structured support.

Here are five key studies on constructivism and its application in classroom learning, incorporating concepts such as proximal development, active role, mental processes, personal experience, social process, knowledge creation, and constructivist framework:

1. Psychology for the Classroom: Constructivism and Social Learning by A. Pritchard & J. Woollard (2010)

Summary: This study discusses the application of constructivist and social learning theories in the classroom, emphasising the active role of students in their learning process and knowledge creation through e-learning and multimedia.

2. Constructivism and Science Performing Skill Among Elementary Students: A Study by Sambit Padhi & P. Dash (2016)

Summary: The research demonstrates how a constructivist teaching approach significantly improves elementary students' science performance skills, aligning with the philosophy of education that promotes active learning and mental processes.

3. Constructivist Approaches for Teaching and Learning of Science by S. Yaduvanshi & Sunita Singh (2015)

Summary: This study highlights how constructivist teaching-learning approaches in science classrooms enhance understanding and engagement, promoting critical thinking and reflecting the philosophy of personal experience and social process in knowledge creation.

4. Mengukur Keefektifan Teori Konstruktivisme dalam Pembelajaran by M. A. Saputro & Poetri Leharia Pakpahan (2021)

Summary: This study explores the effectiveness of the constructivist theory in learning at the secondary school level, emphasising its role in developing children's cognitive abilities and understanding within a constructivist framework.

5. Students' Perceptions of Constructivist Learning in a Community College American History II Survey Course by J. Maypole & T. G. Davies (2001)

Summary: The paper presents findings from a study on constructivist learning in an American History II survey course, showing increased critical thinking and cognitive development, thereby illustrating the constructivist framework's impact on students' proximal development.

These studies offer insights into the implementation of constructivism in various educational contexts, highlighting its efficacy in encouraging an active role in learning, enhancing mental processes, and shaping personal experiences as part of the social process of knowledge creation.