Cognitive Dissonance

Explore cognitive dissonance theory and neural mechanisms in the anterior cingulate cortex, plus practical classroom applications for reducing conflicts.

Explore cognitive dissonance theory and neural mechanisms in the anterior cingulate cortex, plus practical classroom applications for reducing conflicts.

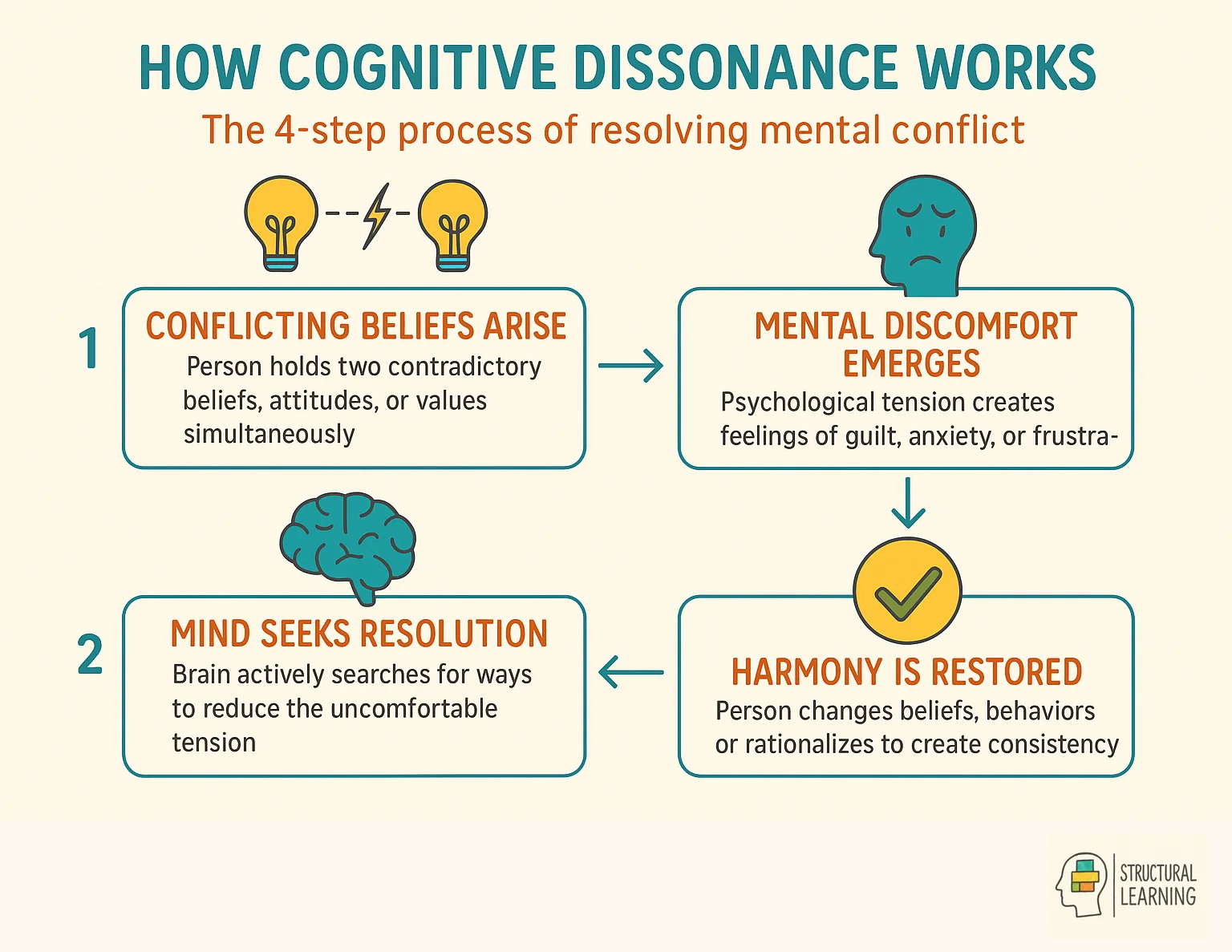

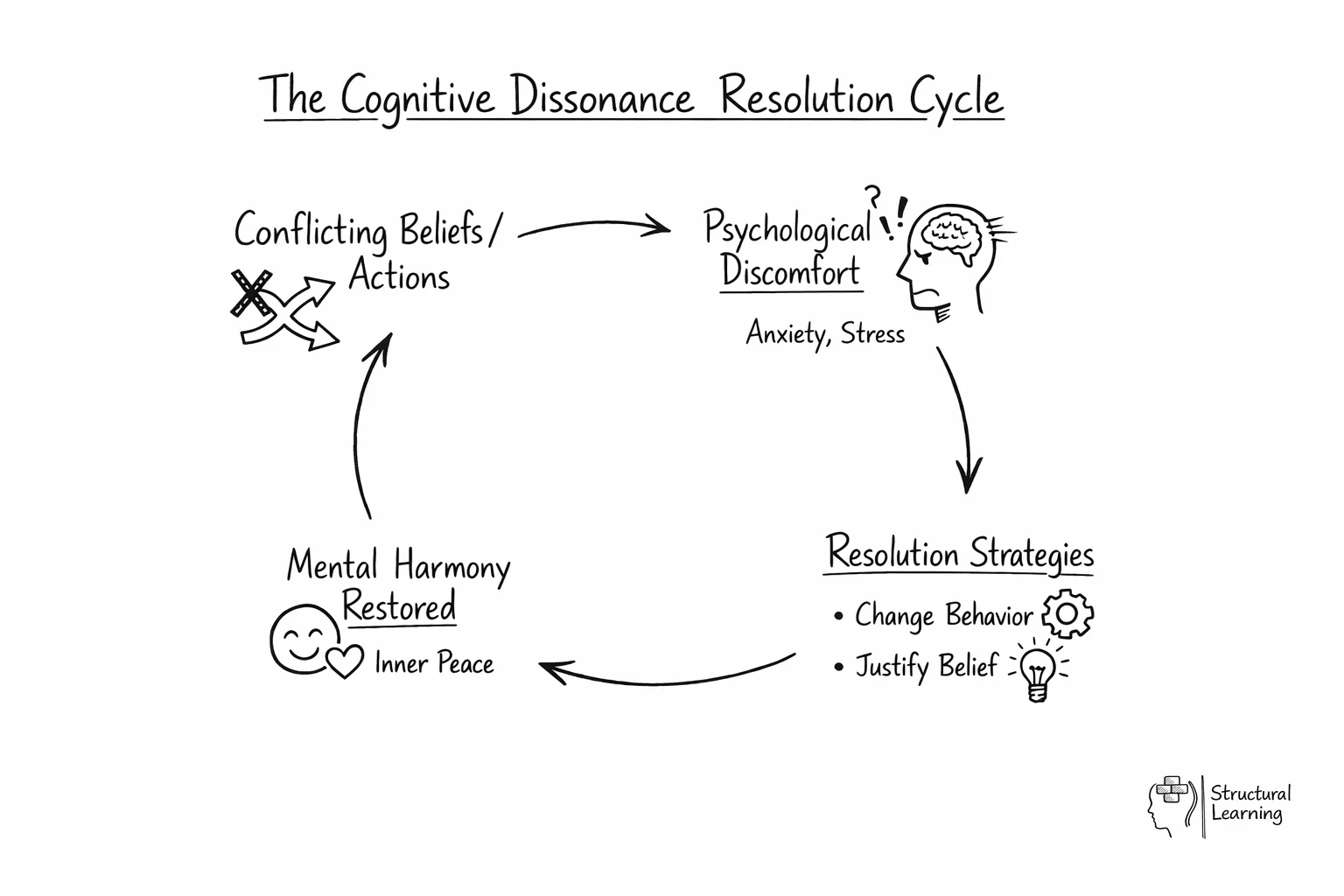

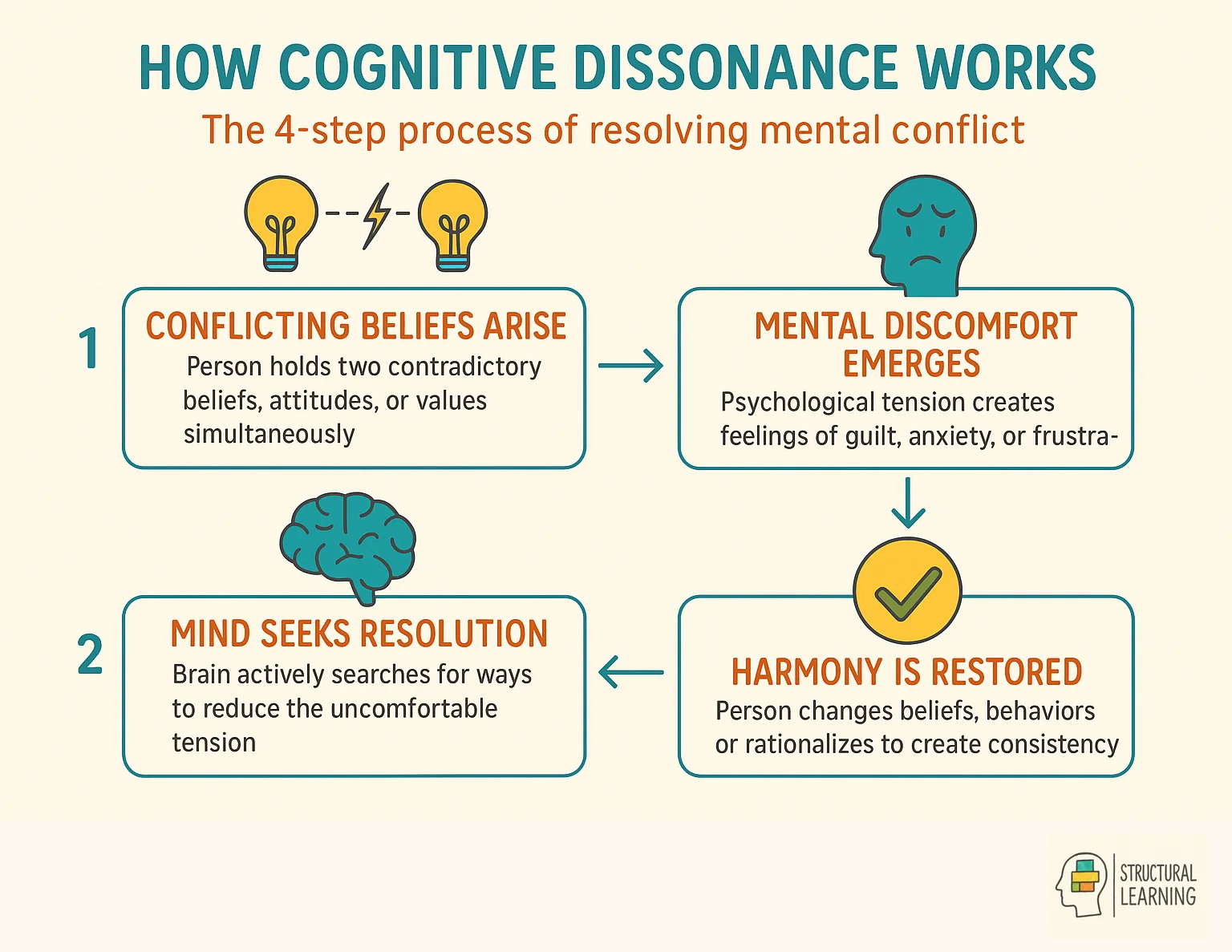

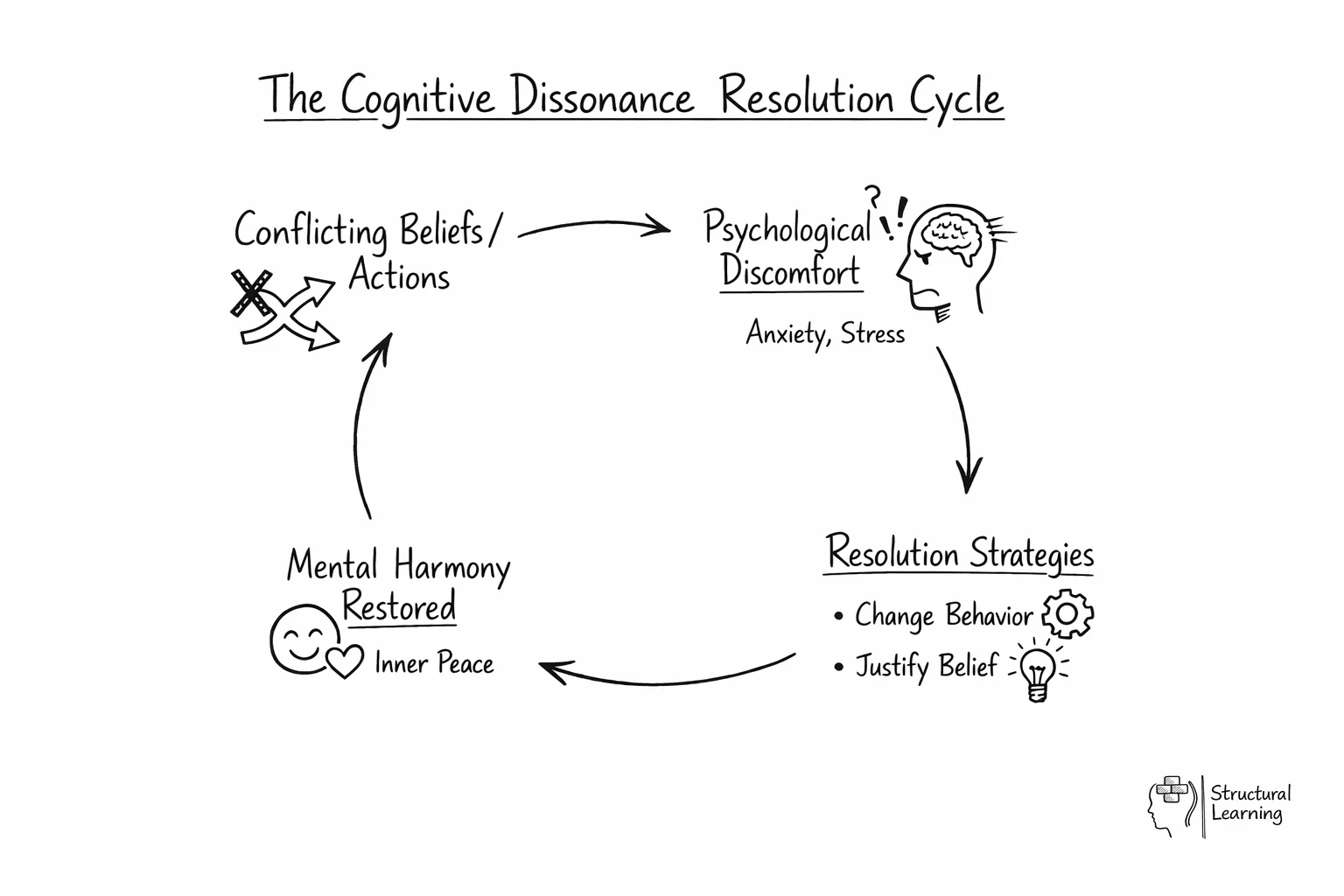

Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological tension that arises when a person holds two or more incongruous beliefs, attitudes, or personal values at the same time. This mental discord creates discomfort that can show up as guilt, anxiety, or frustration. In 2025, understanding this conflict feels more relevant than ever as social media, political divides, and constant information flow make it harder to maintain consistent beliefs and actions, as our mental processing capacity becomes overwhelmed, a concept explored in cognitive load theory.

Leon Festinger first introduced the idea in A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance , arguing that when individuals sense a clash between what they believe and what they do, they feel compelled to resolve it. Often, this happens through rationalisation, finding reasons to justify conflicting choices, or by adjusting attitudes to match behaviour. These processes rely on our existing mental frameworksto make sense of inconsistent information, drawing on principles of cognitive devel opment to understand how beliefs adapt. For example, someone who values animal welfare but eats meat might reduce discomfort by believing animals are treated humanely or by cutting back on meat consumption.

Choice-induced attitude change is another common reaction, where people shift their beliefs after ma king a decision to make their choices feel justified. This concept has been explored widely, from experiments in induced compliance to studies of consumer habits and even the rise of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. And self-regulation and self-perception theory also play roles in how people cope with these internal conflicts, often requiring critical thinkingto navigate, demonstrating that we often go to great lengths to achieve a sense of internal harmony. Developing metacognitive awareness and understanding mental schemas can help individuals recognise and address these internal conflicts more effectively.

Key Takeaways:

Cognitive dissonance theory was developed by Leon Festinger in 1957 with the publication of 'A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance'. The theory emerged from early 20th century social psychology research exploring why people struggle to maintain consistent beliefs. Since its introduction, the theory has evolved through decades of experimental research and practical applications across psychology, marketing, and social sciences.

The roots of this idea can be traced back to the early 20th century, when social psychologists first began exploring why people struggle to maintain consistent beliefs and behaviours. As interest in human motivation and social pressure grew, researchers noticed that holding conflicting ideas could create persistent mental discomfort.

It was in 1957 that Leon Festinger formally defined this experience in his groundbreaking book. Festinger described it as the tension that arises when our actions clash with our convictions or when two beliefs pull us in different directions. He proposed that individuals are driven to resolve this inner conflict, either by adjusting their attitudes, changing their behaviours, or actively seeking information that reassures them their choices are correct.

Over the decades that followed, the concept quickly gained traction across psychology and beyond. In the 1960s and 70s, researchers conducted experiments demonstrating how people might justify questionable decisions to preserve a positive self-image. Scholars began studying the role of personal responsibility, the strength of opposing beliefs, and the power of social influence in shaping how we reconcile these clashes.

By the late 20th century, this framework had expanded into fields such as communication, marketing, and organisational behaviour. It offered fresh insight into why persuasion works, why false beliefs can be so persistent, and how public commitment can deepen conviction. Today, the theory continues to illuminate the intricate links between thought, feeling, and action, helping us understand how people navigate a world full of competing demands and ideas.

Key Points:

Cognitive dissonance can significantly impact how we process language and make decisions. When faced with conflicting information, our attention may become divided as we attempt to reconcile opposing viewpoints. This internal struggle can affect our thinking strategies and lead us to engage in selective reasoning or cognitive biases to reduce the psychological discomfort. The resolution process often requires self-regulation skills to objectively evaluate contradictory evidence and adjust our understanding accordingly.

In educational settings, teachers can identify cognitive dissonance in students through several linguistic markers. Students may use qualifying language such as 'I suppose' or 'maybe', exhibit hesitation patterns in their speech, or provide contradictory explanations within the same discussion. Research shows that learners experiencing dissonance often shift between different reasoning strategies mid-conversation, particularly when confronting concepts that challenge their established worldview.

The cognitive load associated with dissonance significantly impacts learning processes. Students may demonstrate impaired working memory when processing information that conflicts with their beliefs, leading to reduced com prehension and retention. In the classroom, this manifests as students appearing to understand new material during instruction but struggling to apply or recall it later. Teachers often observe this phenomenon when introducing scientific concepts that contradict students' everyday experiences or cultural beliefs.

Effective educators can support students through cognitive dissonance by recognising these patterns and providing structured opportunities for gradual belief adjustment. Creating safe spaces for students to voice uncertainties, encouraging metacognitive reflection, and presenting information in smaller, manageable segments can help reduce the cognitive burden and facilitate more effective learning outcomes.

Cognitive dissonance theory manifests frequently in educational settings, creating challenges for both students and teachers. Research shows that students often experience dissonance when encountering information that contradicts their existing beliefs or knowledge. For instance, a student who believes they are naturally gifted in mathematics may experience significant psychological discomfort when consistently struggling with advanced concepts, leading them to either dismiss the difficulty of the material or avoid engaging with challenging problems altogether.

Teachers themselves are not immune to cognitive dissonance in the classroom. An educator who prides themselves on being student-centred may feel uncomfortable when they find themselves lecturing for extended periods due to curriculum pressures. This internal conflict between their educational philosophy and actual practice can result in rationalising behaviour, such as convincing themselves that direct instruction is temporarily necessary whilst secretly feeling they are compromising their pedagogical values.

Recognising these patterns enables educators to address cognitive dissonance constructively. When students resist new information that challenges their worldview, teachers can acknowledge this discomfort as a natural part of learning, creating safe spaces for intellectual growth. Similarly, educators experiencing their own dissonance can use it as an opportunity for professional reflection, examining whether their practices truly align with their stated beliefs about effective teaching and learning.

When individuals experience cognitive dissonance, they instinctively seek to reduce the uncomfortable tension through several key strategies. Research shows that people typically resolve dissonance by changing their attitudes, modifying their behaviours, or adding new cognitions that justify the inconsistency. Leon Festinger's original work identified that individuals will often choose the path of least resistance, meaning they're more likely to adjust the cognition that feels less important or fixed to them.

In educational settings, students commonly reduce dissonance by rationalising poor performance rather than acknowledging inadequate preparation. For instance, a student who fails an exam despite minimal study might blame the teacher's methods or claim the test was unfair, rather than accepting their lack of effort. Teachers can recognise this pattern and gently guide students towards more productive dissonance resolution by helping them reframe challenges as learning opportunities.

Educational professionals can support healthier dissonance resolution by creating classroom environments that normalise mistakes and growth. When students feel safe to acknowledge inconsistencies between their goals and actions, they're more likely to adjust their behaviours constructively rather than defensively rationalising poor outcomes. This approach transforms cognitive dissonance from a barrier into a powerful catalyst for genuine learning and self-improvement.

Cognitive dissonance theory offers powerful opportunities for educators to enhance learning outcomes by strategically creating moments of productive confusion. When students encounter information that conflicts with their existing beliefs or assumptions, the resulting discomfort motivates them to actively engage with new material rather than passively absorbing it. Research shows that this psychological tension can be particularly effective in subjects where misconceptions are common, such as science, history, and mathematics.

In practice, teachers can harness cognitive dissonance by presenting contradictory evidence or challenging students' preconceptions through carefully designed activities. For example, a physics teacher might demonstrate that heavier objects don't always fall faster, directly contradicting students' intuitive beliefs. Similarly, history educators can present multiple perspectives on historical events, creating dissonance between students' simplified understanding and the complex reality of historical narratives.

The key to successful implementation lies in providing appropriate scaffolding to help students resolve the dissonance constructively. Teachers must guide learners thr ough the discomfort, offering support and resources that enable them to reconcile conflicting information. This approach transforms confusion from a barrier into a catalyst for deeper understanding, encouraging students to actively reconstruct their knowledge rather than simply memorising facts.

Cognitive dissonance theory offers valuable insights into student motivation and learning processes, particularly when learners encounter information that challenges their existing beliefs or understanding. When students face contradictory evidence or concepts that conflict with their prior knowledge, the resulting psychological tension can either motivate deeper learning or lead to defensive rejection of new material. Educational research shows that this discomfort, when managed effectively, creates optimal conditions for meaningful learning and conceptual change.

In the classroom, teachers can harness cognitive dissonance by presenting carefully structured challenges that expose gaps or inconsistencies in students' thinking. For instance, science educators might demonstrate experiments that contradict students' intuitive physics concepts, whilst history teachers could present primary sources that challenge popular historical narratives. The key lies in creating just enough cognitive tension to motivate learning without overwhelming students, as excessive dissonance can lead to anxiety and disengagement rather than productive learning.

Effective implementation requires teachers to provide scaffolded support as students work through their cognitive conflicts. This includes encouraging open discussion of conflicting ideas, validating students' initial thinking whilst guiding them towards more accurate understanding, and allowing sufficient time for mental reorganisation. When students successfully resolve cognitive dissonance through learning, they often experience increased confidence and stronger retention of new concepts.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cognitive dissonance and its application in educational settings.

Translanguaging pedagogies in a Mandarin-English dual language bilingual education classroom: contextualised learning from teacher-researcher collaboration View study ↗26 citations

Tian et al. (2022)

This study examines how teachers navigate the use of both Mandarin and English languages in a dual language bilingual education classroom through collaborative research with university partners. The research is relevant to teachers because it demonstrates how educators can experience cognitive dissonance when balancing competing pedagogical approaches and language policies, and shows how teacher-researcher collaboration can help resolve these tensions by developing contextually appropriate teaching strategies.

From student to teacher: changes in preservice teacher educational beliefs throughout the learning-to-teach journey View study ↗68 citations

Wall et al. (2016)

This research tracks how preservice teachers' educational beliefs and attitudes change as they progress through their teacher preparation program from student to practicing educator. The study is particularly relevant to understanding cognitive dissonance because it documents the psychological tension that occurs when new teachers encounter conflicts between their initial beliefs about teaching and the realities of classroom practice, and how they resolve these contradictions.

Effectiveness of climate change education, a meta-analysis View study ↗14 citations

Aeschbach et al. (2025)

This meta-analysis examines the effectiveness of various climate change education approaches in promoting student learning and climate literacy across multiple studies. For teachers, this research highlights the cognitive dissonance that can arise when trying to teach controversial or emotionally charged topics like climate change, where students may resist information that conflicts with their existing beliefs or family values.

Evaluating the impact of a medical school cohort sexual health course on knowledge, counseling skills and sexual attitude change View study ↗21 citations

Ross et al. (2021)

This study evaluates how a mandatory sexual health course in medical school affects students' knowledge, counseling skills, and attitudes toward sexuality topics. The research is relevant to teachers because it demonstrates how educational interventions can help reduce cognitive dissonance around sensitive subjects by providing factual information and professional training that helps students reconcile personal beliefs with professional responsibilities.

Teachers’ attitude towards education for sustainable development: A descriptive research View study ↗17 citations

Peedikayil et al. (2023)

This descriptive research investigates teachers' attitudes toward education for sustainable development and their role in promoting environmental and social responsibility in schools. The study relates to cognitive dissonance by examining how teachers balance potentially conflicting demands between traditional curriculum requirements and newer sustainability education goals, and how their personal environmental beliefs may conflict with institutional constraints.

Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological tension that arises when a person holds two or more incongruous beliefs, attitudes, or personal values at the same time. This mental discord creates discomfort that can show up as guilt, anxiety, or frustration. In 2025, understanding this conflict feels more relevant than ever as social media, political divides, and constant information flow make it harder to maintain consistent beliefs and actions, as our mental processing capacity becomes overwhelmed, a concept explored in cognitive load theory.

Leon Festinger first introduced the idea in A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance , arguing that when individuals sense a clash between what they believe and what they do, they feel compelled to resolve it. Often, this happens through rationalisation, finding reasons to justify conflicting choices, or by adjusting attitudes to match behaviour. These processes rely on our existing mental frameworksto make sense of inconsistent information, drawing on principles of cognitive devel opment to understand how beliefs adapt. For example, someone who values animal welfare but eats meat might reduce discomfort by believing animals are treated humanely or by cutting back on meat consumption.

Choice-induced attitude change is another common reaction, where people shift their beliefs after ma king a decision to make their choices feel justified. This concept has been explored widely, from experiments in induced compliance to studies of consumer habits and even the rise of eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. And self-regulation and self-perception theory also play roles in how people cope with these internal conflicts, often requiring critical thinkingto navigate, demonstrating that we often go to great lengths to achieve a sense of internal harmony. Developing metacognitive awareness and understanding mental schemas can help individuals recognise and address these internal conflicts more effectively.

Key Takeaways:

Cognitive dissonance theory was developed by Leon Festinger in 1957 with the publication of 'A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance'. The theory emerged from early 20th century social psychology research exploring why people struggle to maintain consistent beliefs. Since its introduction, the theory has evolved through decades of experimental research and practical applications across psychology, marketing, and social sciences.

The roots of this idea can be traced back to the early 20th century, when social psychologists first began exploring why people struggle to maintain consistent beliefs and behaviours. As interest in human motivation and social pressure grew, researchers noticed that holding conflicting ideas could create persistent mental discomfort.

It was in 1957 that Leon Festinger formally defined this experience in his groundbreaking book. Festinger described it as the tension that arises when our actions clash with our convictions or when two beliefs pull us in different directions. He proposed that individuals are driven to resolve this inner conflict, either by adjusting their attitudes, changing their behaviours, or actively seeking information that reassures them their choices are correct.

Over the decades that followed, the concept quickly gained traction across psychology and beyond. In the 1960s and 70s, researchers conducted experiments demonstrating how people might justify questionable decisions to preserve a positive self-image. Scholars began studying the role of personal responsibility, the strength of opposing beliefs, and the power of social influence in shaping how we reconcile these clashes.

By the late 20th century, this framework had expanded into fields such as communication, marketing, and organisational behaviour. It offered fresh insight into why persuasion works, why false beliefs can be so persistent, and how public commitment can deepen conviction. Today, the theory continues to illuminate the intricate links between thought, feeling, and action, helping us understand how people navigate a world full of competing demands and ideas.

Key Points:

Cognitive dissonance can significantly impact how we process language and make decisions. When faced with conflicting information, our attention may become divided as we attempt to reconcile opposing viewpoints. This internal struggle can affect our thinking strategies and lead us to engage in selective reasoning or cognitive biases to reduce the psychological discomfort. The resolution process often requires self-regulation skills to objectively evaluate contradictory evidence and adjust our understanding accordingly.

In educational settings, teachers can identify cognitive dissonance in students through several linguistic markers. Students may use qualifying language such as 'I suppose' or 'maybe', exhibit hesitation patterns in their speech, or provide contradictory explanations within the same discussion. Research shows that learners experiencing dissonance often shift between different reasoning strategies mid-conversation, particularly when confronting concepts that challenge their established worldview.

The cognitive load associated with dissonance significantly impacts learning processes. Students may demonstrate impaired working memory when processing information that conflicts with their beliefs, leading to reduced com prehension and retention. In the classroom, this manifests as students appearing to understand new material during instruction but struggling to apply or recall it later. Teachers often observe this phenomenon when introducing scientific concepts that contradict students' everyday experiences or cultural beliefs.

Effective educators can support students through cognitive dissonance by recognising these patterns and providing structured opportunities for gradual belief adjustment. Creating safe spaces for students to voice uncertainties, encouraging metacognitive reflection, and presenting information in smaller, manageable segments can help reduce the cognitive burden and facilitate more effective learning outcomes.

Cognitive dissonance theory manifests frequently in educational settings, creating challenges for both students and teachers. Research shows that students often experience dissonance when encountering information that contradicts their existing beliefs or knowledge. For instance, a student who believes they are naturally gifted in mathematics may experience significant psychological discomfort when consistently struggling with advanced concepts, leading them to either dismiss the difficulty of the material or avoid engaging with challenging problems altogether.

Teachers themselves are not immune to cognitive dissonance in the classroom. An educator who prides themselves on being student-centred may feel uncomfortable when they find themselves lecturing for extended periods due to curriculum pressures. This internal conflict between their educational philosophy and actual practice can result in rationalising behaviour, such as convincing themselves that direct instruction is temporarily necessary whilst secretly feeling they are compromising their pedagogical values.

Recognising these patterns enables educators to address cognitive dissonance constructively. When students resist new information that challenges their worldview, teachers can acknowledge this discomfort as a natural part of learning, creating safe spaces for intellectual growth. Similarly, educators experiencing their own dissonance can use it as an opportunity for professional reflection, examining whether their practices truly align with their stated beliefs about effective teaching and learning.

When individuals experience cognitive dissonance, they instinctively seek to reduce the uncomfortable tension through several key strategies. Research shows that people typically resolve dissonance by changing their attitudes, modifying their behaviours, or adding new cognitions that justify the inconsistency. Leon Festinger's original work identified that individuals will often choose the path of least resistance, meaning they're more likely to adjust the cognition that feels less important or fixed to them.

In educational settings, students commonly reduce dissonance by rationalising poor performance rather than acknowledging inadequate preparation. For instance, a student who fails an exam despite minimal study might blame the teacher's methods or claim the test was unfair, rather than accepting their lack of effort. Teachers can recognise this pattern and gently guide students towards more productive dissonance resolution by helping them reframe challenges as learning opportunities.

Educational professionals can support healthier dissonance resolution by creating classroom environments that normalise mistakes and growth. When students feel safe to acknowledge inconsistencies between their goals and actions, they're more likely to adjust their behaviours constructively rather than defensively rationalising poor outcomes. This approach transforms cognitive dissonance from a barrier into a powerful catalyst for genuine learning and self-improvement.

Cognitive dissonance theory offers powerful opportunities for educators to enhance learning outcomes by strategically creating moments of productive confusion. When students encounter information that conflicts with their existing beliefs or assumptions, the resulting discomfort motivates them to actively engage with new material rather than passively absorbing it. Research shows that this psychological tension can be particularly effective in subjects where misconceptions are common, such as science, history, and mathematics.

In practice, teachers can harness cognitive dissonance by presenting contradictory evidence or challenging students' preconceptions through carefully designed activities. For example, a physics teacher might demonstrate that heavier objects don't always fall faster, directly contradicting students' intuitive beliefs. Similarly, history educators can present multiple perspectives on historical events, creating dissonance between students' simplified understanding and the complex reality of historical narratives.

The key to successful implementation lies in providing appropriate scaffolding to help students resolve the dissonance constructively. Teachers must guide learners thr ough the discomfort, offering support and resources that enable them to reconcile conflicting information. This approach transforms confusion from a barrier into a catalyst for deeper understanding, encouraging students to actively reconstruct their knowledge rather than simply memorising facts.

Cognitive dissonance theory offers valuable insights into student motivation and learning processes, particularly when learners encounter information that challenges their existing beliefs or understanding. When students face contradictory evidence or concepts that conflict with their prior knowledge, the resulting psychological tension can either motivate deeper learning or lead to defensive rejection of new material. Educational research shows that this discomfort, when managed effectively, creates optimal conditions for meaningful learning and conceptual change.

In the classroom, teachers can harness cognitive dissonance by presenting carefully structured challenges that expose gaps or inconsistencies in students' thinking. For instance, science educators might demonstrate experiments that contradict students' intuitive physics concepts, whilst history teachers could present primary sources that challenge popular historical narratives. The key lies in creating just enough cognitive tension to motivate learning without overwhelming students, as excessive dissonance can lead to anxiety and disengagement rather than productive learning.

Effective implementation requires teachers to provide scaffolded support as students work through their cognitive conflicts. This includes encouraging open discussion of conflicting ideas, validating students' initial thinking whilst guiding them towards more accurate understanding, and allowing sufficient time for mental reorganisation. When students successfully resolve cognitive dissonance through learning, they often experience increased confidence and stronger retention of new concepts.

These peer-reviewed studies provide deeper insights into cognitive dissonance and its application in educational settings.

Translanguaging pedagogies in a Mandarin-English dual language bilingual education classroom: contextualised learning from teacher-researcher collaboration View study ↗26 citations

Tian et al. (2022)

This study examines how teachers navigate the use of both Mandarin and English languages in a dual language bilingual education classroom through collaborative research with university partners. The research is relevant to teachers because it demonstrates how educators can experience cognitive dissonance when balancing competing pedagogical approaches and language policies, and shows how teacher-researcher collaboration can help resolve these tensions by developing contextually appropriate teaching strategies.

From student to teacher: changes in preservice teacher educational beliefs throughout the learning-to-teach journey View study ↗68 citations

Wall et al. (2016)

This research tracks how preservice teachers' educational beliefs and attitudes change as they progress through their teacher preparation program from student to practicing educator. The study is particularly relevant to understanding cognitive dissonance because it documents the psychological tension that occurs when new teachers encounter conflicts between their initial beliefs about teaching and the realities of classroom practice, and how they resolve these contradictions.

Effectiveness of climate change education, a meta-analysis View study ↗14 citations

Aeschbach et al. (2025)

This meta-analysis examines the effectiveness of various climate change education approaches in promoting student learning and climate literacy across multiple studies. For teachers, this research highlights the cognitive dissonance that can arise when trying to teach controversial or emotionally charged topics like climate change, where students may resist information that conflicts with their existing beliefs or family values.

Evaluating the impact of a medical school cohort sexual health course on knowledge, counseling skills and sexual attitude change View study ↗21 citations

Ross et al. (2021)

This study evaluates how a mandatory sexual health course in medical school affects students' knowledge, counseling skills, and attitudes toward sexuality topics. The research is relevant to teachers because it demonstrates how educational interventions can help reduce cognitive dissonance around sensitive subjects by providing factual information and professional training that helps students reconcile personal beliefs with professional responsibilities.

Teachers’ attitude towards education for sustainable development: A descriptive research View study ↗17 citations

Peedikayil et al. (2023)

This descriptive research investigates teachers' attitudes toward education for sustainable development and their role in promoting environmental and social responsibility in schools. The study relates to cognitive dissonance by examining how teachers balance potentially conflicting demands between traditional curriculum requirements and newer sustainability education goals, and how their personal environmental beliefs may conflict with institutional constraints.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-dissonance#article","headline":"Cognitive Dissonance","description":"Explore cognitive dissonance theory and its neural mechanisms, from anterior cingulate cortex activity to practical classroom applications for reducing...","datePublished":"2023-06-25T15:46:45.856Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-dissonance"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/6952507ff7eac78ee2c01d35_6952507d43ac9a07f30b80d9_cognitive-dissonance-infographic.webp","wordCount":4376},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-dissonance#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Cognitive Dissonance","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/cognitive-dissonance"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is the Cognitive Dissonance Theory?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological tension that arises when a person holds two or more incongruous beliefs, attitudes, or personal values at the same time. This mental discord creates discomfort that can show up as guilt, anxiety, or frustration. In 2025, understanding this conflict feels more relevant than ever as social media, political divides, and constant information flow make it harder to maintain consistent beliefs and actions, as our mental processing capacity becomes overw"}},{"@type":"Question","name":"When Was Cognitive Dissonance Theory Developed?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cognitive dissonance theory was developed by Leon Festinger in 1957 with the publication of 'A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance'. The theory emerged from early 20th century social psychology research exploring why people struggle to maintain consistent beliefs. Since its introduction, the theory has evolved through decades of experimental research and practical applications across psychology, marketing, and social sciences."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How Does Cognitive Dissonance Affect Language and Thinking?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"Cognitive dissonance can significantly impact how we process language and make decisions. When faced with conflicting information, our attention may become divided as we attempt to reconcile opposing viewpoints. This internal struggle can affect our thinking strategies and lead us to engage in selective reasoning or cognitive biases to reduce the psychological discomfort. The resolution process often requires self-regulation skills to objectively evaluate contradictory evidence and adjust our un"}}]}]}