Cognitive Biases

Explore practical steps to identify and overcome common cognitive biases, enhancing decision-making and critical thinking.

Explore practical steps to identify and overcome common cognitive biases, enhancing decision-making and critical thinking.

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input.

An individual's construction of social reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the social world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality.

Although cognitive biases are a pervasive aspect of human cognition, they are not necessarily all maladaptive. They can be seen as a byproduct of the brain's attempt to simplify information processing.

They are often a result of the brain's limited information processing capacity and can be seen as mental shortcuts that usually get us where we need to go – but sometimes lead us astray.

Here are three key points that summarize what cognitive biases are:

Throughout this article, we will delve into various biases, such as the self-serving bias, which describes our tendency to attribute successes to internal factors and failures to external ones, and the actor-observer bias, where we tend to attribute other people's actions to their character but our own actions to our circumstances.

We will also explore how these biases influence our view of rationality and how common biases can lead to a blind spot in our own self-awareness. From the fundamental attribution error outlined in social psychology to the insights from positive psychology on optimism bias, we'll provide a deeper understanding of these concepts, informed by sources like the APA Dictionary of Psychology and experimental social psychology research.

Cognitive biases were first identified and studied by a number of influential psychologists, each of whom made significant contributions to the field. This list showcases key researchers from the field of cognitive biases, each contributing a building block to our current understanding of the topic.

As the article progresses, we will delve deeper into each bias, exploring its origins, implications, and real-world applications, solidifying the reader's comprehension of this complex field.

1. Peter Wason (1924–2003): A cognitive psychologist at University College London, Wason was instrumental in identifying various logical fallacies and cognitive biases, notably the confirmation bias through his eponymous Wason selection task. His research in the 1960s demonstrated the human tendency to seek information that confirms pre-existing beliefs.

2. Robert H. Thouless (1894–1984): Thouless contributed to the early exploration of cognitive biases with his work on wishful thinking and the distortion of evidence. He was a psychologist at Cambridge University Press, and his research in the 1950s delved into the psychology of judgment and decision-making.

3. Amos Tversky (1937–1996) & Daniel Kahneman (b. 1934): Tversky and Kahneman, through their work published by Oxford University Press and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, revolutionized the understanding of human judgment. In the 1970s, they developed prospect theory and uncovered heuristics such as the availability and representativeness biases, fundamentally shaping the field of cognitive science.

4. Gerd Gigerenzer (b. 1947): Gigerenzer's research focuses on the role of heuristics in decision-making. He has contributed to the understanding of how people make decisions under uncertainty and is known for his critique of the work of Kahneman and Tversky, emphasizing the adaptive nature of heuristics.

5. Daniel L. Schacter (b. 1952): Schacter's work at Harvard University has been pivotal in exploring memory biases, especially false memories. His research in cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience has shed light on the mechanisms of memory distortion and their implications for cognitive biases.

6. Keith E. Stanovich (b. 1950): Stanovich's work on the Rationality Quotient has been significant in understanding cognitive biases. His research investigates the discrepancy between normative and descriptive models of decision-making, highlighting the influence of cognitive biases on rational thought processes.

7. Daniel M. Wegner (1948–2013): Wegner, a professor at Harvard, introduced the theory of ironic processes of mental control. His research suggests that attempts to suppress certain thoughts make them more likely to surface, contributing to a better understanding of counterintuitive biases in thought suppression.

8. Kahneman D & Tversky A: Beyond their individual contributions, Kahneman and Tversky's collaboration produced some of the most influential papers in the field of cognitive biases, such as their work on the framing effect and loss aversion, which has influenced disciplines ranging from economics to health care.

9. Caryn L. Morewedge (b. 20th Century) & Daniel T. Gilbert (b. 1957): Their work has advanced the understanding of biases in affective forecasting, demonstrating how people's predictions about their emotional reactions to future events are often inaccurate.

10. Marinus H. van IJzendoorn & Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg: This duo has contributed to understanding the interplay between attachment styles and cognitive biases, showing how early life experiences can influence the processing of social information and decision-making.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky made significant contributions to the study of cognitive biases by focusing on heuristics and biases in decision making. Their research had a substantial impact on behavioral economics, shedding light on the ways in which individuals often deviate from rational decision-making models.

Key findings from their research include the identification of various cognitive biases, such as the availability heuristic and the representativeness heuristic. The availability heuristic refers to the tendency to rely on examples that come to mind easily when making decisions, often leading to overestimation of the likelihood of certain events.

The representativeness heuristic involves making judgments based on how similar something is to a typical case, which can lead to errors in decision making.

Their work has shaped the understanding of cognitive biases by demonstrating the ways in which individuals consistently make irrational decisions due to the use of heuristics. This has implications for fields such as marketing, finance, and public policy, as understanding and addressing these biases is crucial for influencing consumer behavior and improving decision making. In summary, Kahneman and Tversky's research has made a lasting impact on the study of cognitive biases and decision making processes.

One of the most influential studies in the field of cognitive psychology was conducted by John Anderson in the late 1970s. Anderson's groundbreaking research focused on memory and information processing, and his key findings revolutionized our understanding of the human mind.

His methodology involved designing computer models to simulate human cognition and behavior, allowing him to uncover the underlying processes involved in learning and memory.

Anderson's research revealed that memory is not a single, unified system, but rather a combination of separate components that work together to encode, store, and retrieve information. This insight significantly contributed to our understanding of how we learn and remember, and it laid the groundwork for subsequent research in cognitive psychology.

Anderson's work has shaped current understanding by highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of memory and cognition, and it continues to influence the development of theories and models in the field. His contributions have had a lasting impact on our understanding of human cognition and have paved the way for further advancements in the study of memory and learning processes.

Systematic errors in judgment and decision-making can arise from cognitive biases, affecting the integration of critical data in defining a clinical candidate. Overconfidence, poor calibration of judgments, availability bias, and excess focus on certainty can all impact drug discovery decision-making.

Overconfidence can lead to ignoring or underestimating risks, while poor calibration of judgments can result in inconsistent and unreliable decision-making. Availability bias can cause decision-makers to rely too heavily on readily available information, rather than considering a broad range of data. Excess focus on certainty can lead to a reluctance to consider alternative perspectives or options.

In drug discovery projects, potential bias can arise from arbitrary cut-offs or overreliance on individual parameters, limiting the coverage of parameter space. This can result in overlooking potentially valuable candidates or dismissing promising leads prematurely.

It is important for decision-makers to be aware of these biases and work to mitigate their impact on the evaluation and selection of clinical candidates. Awareness of cognitive biases and their effects on decision-making is crucial for ensuring thorough and effective drug discovery processes.

Cognitive biases subtly shape our daily choices, problem-solving capabilities, and behaviors. Grasping the influence of cognitive biases is vital for identifying their role in our thought processes and actions, which in turn aids in crafting strategies to counteract their less desirable effects.

Influences on Decision-Making

Cognitive biases often disrupt our ability to make decisions rooted in logic and full information. Take confirmation bias, for instance; it may lead someone to cherry-pick data that supports their pre-existing views, disregarding information that doesn't. Such tendencies can result in poorly informed decisions that may not align with one's actual best interests or overlook valuable differing viewpoints.

Impact on Problem-Solving

When it comes to solving problems, cognitive biases can equally steer us astray. Biases like anchoring or the availability heuristic might cause us to overemphasize initial information or readily recalled instances, bypassing a comprehensive evaluation of all relevant data. Consequently, we may settle on solutions that are less than ideal, stifling creativity and the potential for innovative breakthroughs.

Behavioral Outcomes

Cognitive biases can also dictate our behavior, often leading us towards choices that may not serve us well. An overconfidence bias, for example, might embolden someone to assume greater risks than is sensible, whereas a negativity bias can result in an undue focus on the adverse, culminating in a bleak worldview.

In sum, cognitive biases have a broad spectrum of effects on our daily existence, swaying our decision-making, problem-solving, and overall behavior. Awareness and acknowledgment of these biases are critical for making more informed, rational choices and successfully maneuvering through the intricacies of everyday life.

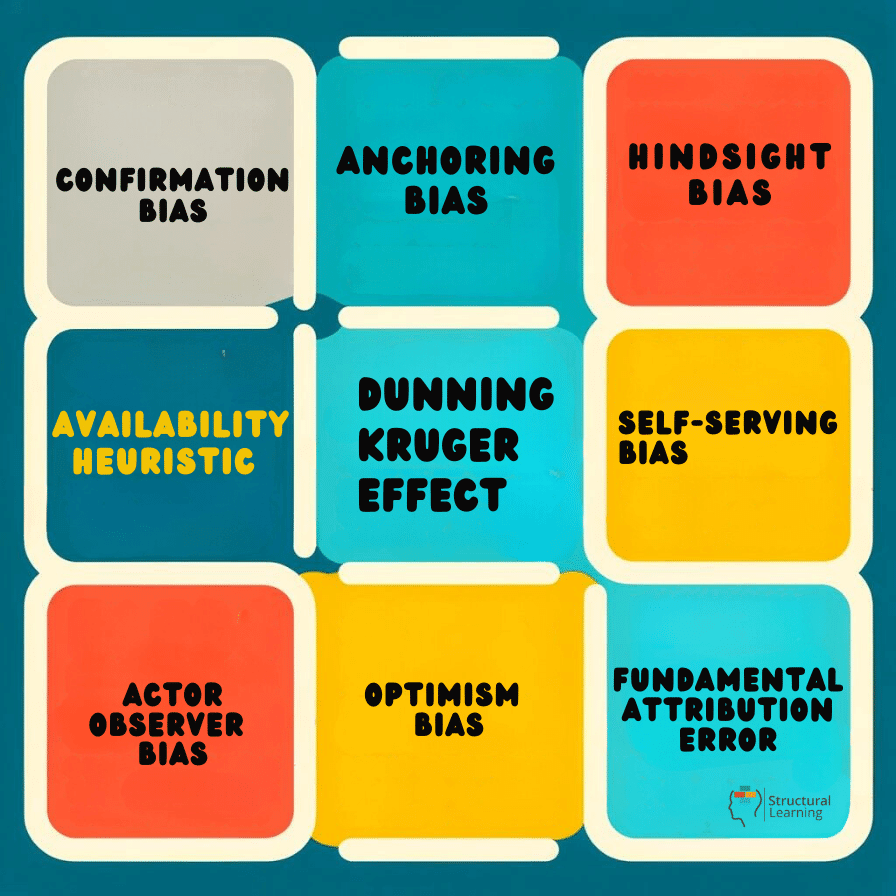

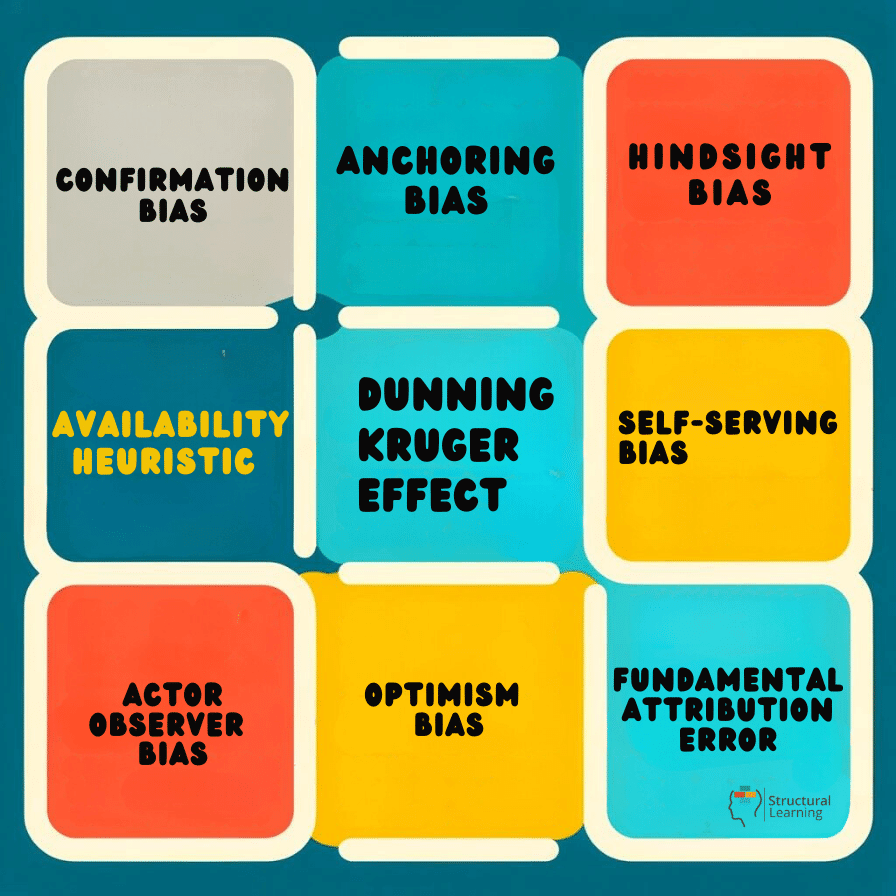

As we have noted, Cognitive biases often act like unseen forces guiding our judgments and decisions. Here are ten of the most common ones:

Understanding these biases can help us reflect on our decision-making processes and strive for more balanced and objective evaluations in our personal and professional lives.

Insights from behavioral economics provide a unique perspective on the ways individuals make decisions, interact with each other, and respond to incentives. This interdisciplinary field combines insights from psychology and economics to understand why people sometimes make irrational choices.

By examining real-world behaviors and decision-making processes, behavioral economics offers valuable insights that can inform public policy, marketing strategies, and financial decision-making.

Understanding the biases and heuristics that drive human behavior can help to predict and influence economic outcomes in ways that traditional economic models cannot. This innovative approach to economics has gained increasing prominence in recent years, as policymakers and businesses seek to better understand and influence individual behavior.

Cognitive biases play a significant role in shaping economic theories and models. For example, the availability heuristic leads individuals to make decisions based on readily available information, often resulting in overestimating the likelihood of certain events.

This can impact financial decision-making, such as investing in stocks based on recent news rather than a thorough analysis of market trends. Additionally, confirmation bias can lead individuals to seek out information that supports their existing beliefs, potentially leading to skewed economic data and flawed models.

These biases have implications for economic predictions and the development of economic policies. For instance, overconfidence bias can lead to overly optimistic economic forecasts, which in turn can influence policy decisions. Furthermore, anchoring bias can cause policymakers to rely too heavily on initial, possibly irrelevant, information, leading to misguided economic policies.

By recognizing the impact of these biases on economic decision-making, we can improve our understanding of economic behavior and enhance the effectiveness of economic policies.

In the workplace, cognitive biases can lead to poor decisions and a deviation from norm, often without individuals realizing the influence these biases have. Here are five fictional examples illustrating this point:

These examples show how cognitive biases can surreptitiously influence human decision-making, leading to negative effects that ripple through the workplace. By being bias blind, companies risk stagnation and the inability to adapt, highlighting the importance of recognizing and mitigating biases in professional environments.

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to adapt one's thinking in response to changing circumstances and to shift attention between different tasks or trains of thought. This mental skill helps individuals to approach problems from different perspectives, consider alternative solutions, and be open to new ideas.

Cognitive flexibility plays a crucial role in overcoming biases by allowing individuals to challenge their own preconceptions and be more open-minded in their reasoning and decision-making.

By understanding how cognitive flexibility serves as an antidote to biases, we can explore the ways in which this cognitive skill can help us to think more critically and make more informed judgments in our daily lives.

Being open-minded and adaptable is crucial in overcoming cognitive biases. By acknowledging the presence of biases, seeking diverse perspectives and experiences, and practicing cognitive flexibility, individuals can better understand and address their own cognitive biases.

Open-mindedness allows for the consideration of different viewpoints, while adaptability enables the integration of new information and the re-evaluation of previously held beliefs.

In understanding and addressing cognitive biases, being open-minded and adaptable also involves being cautious and assertive in facilitating conversations with others. This means being receptive to alternative perspectives while also confidently challenging and questioning one's own and others' biases. By actively engaging in assertive communication, individuals can create an environment where cognitive biases are openly discussed and critically examined.

By fostering open-mindedness and adaptability, individuals can better combat cognitive biases and enhance decision-making processes by valuing diversity of thought and experiences. This allows for a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to problem-solving and decision-making.

Addressing cognitive biases requires conscious effort and reflective thinking. Here’s a practical guide to overcoming some of the most common cognitive biases, which can often lead to errors in judgment and decision-making.

By actively engaging with these strategies, individuals can begin to counteract the thinking errors that cognitive biases present, leading to more rational and effective decision-making.

These studies provide insights into how cognitive biases impact decision-making, perception, and emotion, contributing to our understanding of human and animal psychology.

1. Harding, Paul, & Mendl (2004) found that rats housed in unpredictable conditions exhibit a 'pessimistic' cognitive bias similar to negative judgement biases seen in anxious or depressed humans. This suggests cognitive bias can indicate affective states in animals, aiding in welfare studies.

2. Hallion & Ruscio (2011) conducted a meta-analysis on Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) for anxiety and depression, finding CBM has a medium effect on biases and a small effect on symptoms. The results support cognitive theories of anxiety and depression, suggesting biases' interactive effect with stressors on symptoms.

3. Haselton & Buss (2000) introduced Error Management Theory (EMT), explaining cognitive biases as designed for asymmetrical costs of errors over evolutionary history. Their studies show men overperceive sexual intent, and women underestimate commitment, illustrating how biases can influence social inferences.

4. Curley, Munro, & Lages (2020) emphasize the need for rigorous, ecologically valid research to understand cognitive biases in forensic decisions. They argue for prioritizing assessment of bias prevalence, impact, and type to maintain trust in the justice system.

5. Stanovich & West (2008) found numerous thinking biases uncorrelated with cognitive ability, challenging the assumption that biases are due to lack of intelligence. They suggest that biases like the conjunction effect, framing effects, and myside bias are part of rational thinking under resource constraints.

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input.

An individual's construction of social reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the social world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, or what is broadly called irrationality.

Although cognitive biases are a pervasive aspect of human cognition, they are not necessarily all maladaptive. They can be seen as a byproduct of the brain's attempt to simplify information processing.

They are often a result of the brain's limited information processing capacity and can be seen as mental shortcuts that usually get us where we need to go – but sometimes lead us astray.

Here are three key points that summarize what cognitive biases are:

Throughout this article, we will delve into various biases, such as the self-serving bias, which describes our tendency to attribute successes to internal factors and failures to external ones, and the actor-observer bias, where we tend to attribute other people's actions to their character but our own actions to our circumstances.

We will also explore how these biases influence our view of rationality and how common biases can lead to a blind spot in our own self-awareness. From the fundamental attribution error outlined in social psychology to the insights from positive psychology on optimism bias, we'll provide a deeper understanding of these concepts, informed by sources like the APA Dictionary of Psychology and experimental social psychology research.

Cognitive biases were first identified and studied by a number of influential psychologists, each of whom made significant contributions to the field. This list showcases key researchers from the field of cognitive biases, each contributing a building block to our current understanding of the topic.

As the article progresses, we will delve deeper into each bias, exploring its origins, implications, and real-world applications, solidifying the reader's comprehension of this complex field.

1. Peter Wason (1924–2003): A cognitive psychologist at University College London, Wason was instrumental in identifying various logical fallacies and cognitive biases, notably the confirmation bias through his eponymous Wason selection task. His research in the 1960s demonstrated the human tendency to seek information that confirms pre-existing beliefs.

2. Robert H. Thouless (1894–1984): Thouless contributed to the early exploration of cognitive biases with his work on wishful thinking and the distortion of evidence. He was a psychologist at Cambridge University Press, and his research in the 1950s delved into the psychology of judgment and decision-making.

3. Amos Tversky (1937–1996) & Daniel Kahneman (b. 1934): Tversky and Kahneman, through their work published by Oxford University Press and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, revolutionized the understanding of human judgment. In the 1970s, they developed prospect theory and uncovered heuristics such as the availability and representativeness biases, fundamentally shaping the field of cognitive science.

4. Gerd Gigerenzer (b. 1947): Gigerenzer's research focuses on the role of heuristics in decision-making. He has contributed to the understanding of how people make decisions under uncertainty and is known for his critique of the work of Kahneman and Tversky, emphasizing the adaptive nature of heuristics.

5. Daniel L. Schacter (b. 1952): Schacter's work at Harvard University has been pivotal in exploring memory biases, especially false memories. His research in cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience has shed light on the mechanisms of memory distortion and their implications for cognitive biases.

6. Keith E. Stanovich (b. 1950): Stanovich's work on the Rationality Quotient has been significant in understanding cognitive biases. His research investigates the discrepancy between normative and descriptive models of decision-making, highlighting the influence of cognitive biases on rational thought processes.

7. Daniel M. Wegner (1948–2013): Wegner, a professor at Harvard, introduced the theory of ironic processes of mental control. His research suggests that attempts to suppress certain thoughts make them more likely to surface, contributing to a better understanding of counterintuitive biases in thought suppression.

8. Kahneman D & Tversky A: Beyond their individual contributions, Kahneman and Tversky's collaboration produced some of the most influential papers in the field of cognitive biases, such as their work on the framing effect and loss aversion, which has influenced disciplines ranging from economics to health care.

9. Caryn L. Morewedge (b. 20th Century) & Daniel T. Gilbert (b. 1957): Their work has advanced the understanding of biases in affective forecasting, demonstrating how people's predictions about their emotional reactions to future events are often inaccurate.

10. Marinus H. van IJzendoorn & Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg: This duo has contributed to understanding the interplay between attachment styles and cognitive biases, showing how early life experiences can influence the processing of social information and decision-making.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky made significant contributions to the study of cognitive biases by focusing on heuristics and biases in decision making. Their research had a substantial impact on behavioral economics, shedding light on the ways in which individuals often deviate from rational decision-making models.

Key findings from their research include the identification of various cognitive biases, such as the availability heuristic and the representativeness heuristic. The availability heuristic refers to the tendency to rely on examples that come to mind easily when making decisions, often leading to overestimation of the likelihood of certain events.

The representativeness heuristic involves making judgments based on how similar something is to a typical case, which can lead to errors in decision making.

Their work has shaped the understanding of cognitive biases by demonstrating the ways in which individuals consistently make irrational decisions due to the use of heuristics. This has implications for fields such as marketing, finance, and public policy, as understanding and addressing these biases is crucial for influencing consumer behavior and improving decision making. In summary, Kahneman and Tversky's research has made a lasting impact on the study of cognitive biases and decision making processes.

One of the most influential studies in the field of cognitive psychology was conducted by John Anderson in the late 1970s. Anderson's groundbreaking research focused on memory and information processing, and his key findings revolutionized our understanding of the human mind.

His methodology involved designing computer models to simulate human cognition and behavior, allowing him to uncover the underlying processes involved in learning and memory.

Anderson's research revealed that memory is not a single, unified system, but rather a combination of separate components that work together to encode, store, and retrieve information. This insight significantly contributed to our understanding of how we learn and remember, and it laid the groundwork for subsequent research in cognitive psychology.

Anderson's work has shaped current understanding by highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of memory and cognition, and it continues to influence the development of theories and models in the field. His contributions have had a lasting impact on our understanding of human cognition and have paved the way for further advancements in the study of memory and learning processes.

Systematic errors in judgment and decision-making can arise from cognitive biases, affecting the integration of critical data in defining a clinical candidate. Overconfidence, poor calibration of judgments, availability bias, and excess focus on certainty can all impact drug discovery decision-making.

Overconfidence can lead to ignoring or underestimating risks, while poor calibration of judgments can result in inconsistent and unreliable decision-making. Availability bias can cause decision-makers to rely too heavily on readily available information, rather than considering a broad range of data. Excess focus on certainty can lead to a reluctance to consider alternative perspectives or options.

In drug discovery projects, potential bias can arise from arbitrary cut-offs or overreliance on individual parameters, limiting the coverage of parameter space. This can result in overlooking potentially valuable candidates or dismissing promising leads prematurely.

It is important for decision-makers to be aware of these biases and work to mitigate their impact on the evaluation and selection of clinical candidates. Awareness of cognitive biases and their effects on decision-making is crucial for ensuring thorough and effective drug discovery processes.

Cognitive biases subtly shape our daily choices, problem-solving capabilities, and behaviors. Grasping the influence of cognitive biases is vital for identifying their role in our thought processes and actions, which in turn aids in crafting strategies to counteract their less desirable effects.

Influences on Decision-Making

Cognitive biases often disrupt our ability to make decisions rooted in logic and full information. Take confirmation bias, for instance; it may lead someone to cherry-pick data that supports their pre-existing views, disregarding information that doesn't. Such tendencies can result in poorly informed decisions that may not align with one's actual best interests or overlook valuable differing viewpoints.

Impact on Problem-Solving

When it comes to solving problems, cognitive biases can equally steer us astray. Biases like anchoring or the availability heuristic might cause us to overemphasize initial information or readily recalled instances, bypassing a comprehensive evaluation of all relevant data. Consequently, we may settle on solutions that are less than ideal, stifling creativity and the potential for innovative breakthroughs.

Behavioral Outcomes

Cognitive biases can also dictate our behavior, often leading us towards choices that may not serve us well. An overconfidence bias, for example, might embolden someone to assume greater risks than is sensible, whereas a negativity bias can result in an undue focus on the adverse, culminating in a bleak worldview.

In sum, cognitive biases have a broad spectrum of effects on our daily existence, swaying our decision-making, problem-solving, and overall behavior. Awareness and acknowledgment of these biases are critical for making more informed, rational choices and successfully maneuvering through the intricacies of everyday life.

As we have noted, Cognitive biases often act like unseen forces guiding our judgments and decisions. Here are ten of the most common ones:

Understanding these biases can help us reflect on our decision-making processes and strive for more balanced and objective evaluations in our personal and professional lives.

Insights from behavioral economics provide a unique perspective on the ways individuals make decisions, interact with each other, and respond to incentives. This interdisciplinary field combines insights from psychology and economics to understand why people sometimes make irrational choices.

By examining real-world behaviors and decision-making processes, behavioral economics offers valuable insights that can inform public policy, marketing strategies, and financial decision-making.

Understanding the biases and heuristics that drive human behavior can help to predict and influence economic outcomes in ways that traditional economic models cannot. This innovative approach to economics has gained increasing prominence in recent years, as policymakers and businesses seek to better understand and influence individual behavior.

Cognitive biases play a significant role in shaping economic theories and models. For example, the availability heuristic leads individuals to make decisions based on readily available information, often resulting in overestimating the likelihood of certain events.

This can impact financial decision-making, such as investing in stocks based on recent news rather than a thorough analysis of market trends. Additionally, confirmation bias can lead individuals to seek out information that supports their existing beliefs, potentially leading to skewed economic data and flawed models.

These biases have implications for economic predictions and the development of economic policies. For instance, overconfidence bias can lead to overly optimistic economic forecasts, which in turn can influence policy decisions. Furthermore, anchoring bias can cause policymakers to rely too heavily on initial, possibly irrelevant, information, leading to misguided economic policies.

By recognizing the impact of these biases on economic decision-making, we can improve our understanding of economic behavior and enhance the effectiveness of economic policies.

In the workplace, cognitive biases can lead to poor decisions and a deviation from norm, often without individuals realizing the influence these biases have. Here are five fictional examples illustrating this point:

These examples show how cognitive biases can surreptitiously influence human decision-making, leading to negative effects that ripple through the workplace. By being bias blind, companies risk stagnation and the inability to adapt, highlighting the importance of recognizing and mitigating biases in professional environments.

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to adapt one's thinking in response to changing circumstances and to shift attention between different tasks or trains of thought. This mental skill helps individuals to approach problems from different perspectives, consider alternative solutions, and be open to new ideas.

Cognitive flexibility plays a crucial role in overcoming biases by allowing individuals to challenge their own preconceptions and be more open-minded in their reasoning and decision-making.

By understanding how cognitive flexibility serves as an antidote to biases, we can explore the ways in which this cognitive skill can help us to think more critically and make more informed judgments in our daily lives.

Being open-minded and adaptable is crucial in overcoming cognitive biases. By acknowledging the presence of biases, seeking diverse perspectives and experiences, and practicing cognitive flexibility, individuals can better understand and address their own cognitive biases.

Open-mindedness allows for the consideration of different viewpoints, while adaptability enables the integration of new information and the re-evaluation of previously held beliefs.

In understanding and addressing cognitive biases, being open-minded and adaptable also involves being cautious and assertive in facilitating conversations with others. This means being receptive to alternative perspectives while also confidently challenging and questioning one's own and others' biases. By actively engaging in assertive communication, individuals can create an environment where cognitive biases are openly discussed and critically examined.

By fostering open-mindedness and adaptability, individuals can better combat cognitive biases and enhance decision-making processes by valuing diversity of thought and experiences. This allows for a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to problem-solving and decision-making.

Addressing cognitive biases requires conscious effort and reflective thinking. Here’s a practical guide to overcoming some of the most common cognitive biases, which can often lead to errors in judgment and decision-making.

By actively engaging with these strategies, individuals can begin to counteract the thinking errors that cognitive biases present, leading to more rational and effective decision-making.

These studies provide insights into how cognitive biases impact decision-making, perception, and emotion, contributing to our understanding of human and animal psychology.

1. Harding, Paul, & Mendl (2004) found that rats housed in unpredictable conditions exhibit a 'pessimistic' cognitive bias similar to negative judgement biases seen in anxious or depressed humans. This suggests cognitive bias can indicate affective states in animals, aiding in welfare studies.

2. Hallion & Ruscio (2011) conducted a meta-analysis on Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) for anxiety and depression, finding CBM has a medium effect on biases and a small effect on symptoms. The results support cognitive theories of anxiety and depression, suggesting biases' interactive effect with stressors on symptoms.

3. Haselton & Buss (2000) introduced Error Management Theory (EMT), explaining cognitive biases as designed for asymmetrical costs of errors over evolutionary history. Their studies show men overperceive sexual intent, and women underestimate commitment, illustrating how biases can influence social inferences.

4. Curley, Munro, & Lages (2020) emphasize the need for rigorous, ecologically valid research to understand cognitive biases in forensic decisions. They argue for prioritizing assessment of bias prevalence, impact, and type to maintain trust in the justice system.

5. Stanovich & West (2008) found numerous thinking biases uncorrelated with cognitive ability, challenging the assumption that biases are due to lack of intelligence. They suggest that biases like the conjunction effect, framing effects, and myside bias are part of rational thinking under resource constraints.