Learning Walks: A guide for school leaders

Explore how Learning Walks support school improvement by focusing on student learning, collaboration, and reflective practice.

Explore how Learning Walks support school improvement by focusing on student learning, collaboration, and reflective practice.

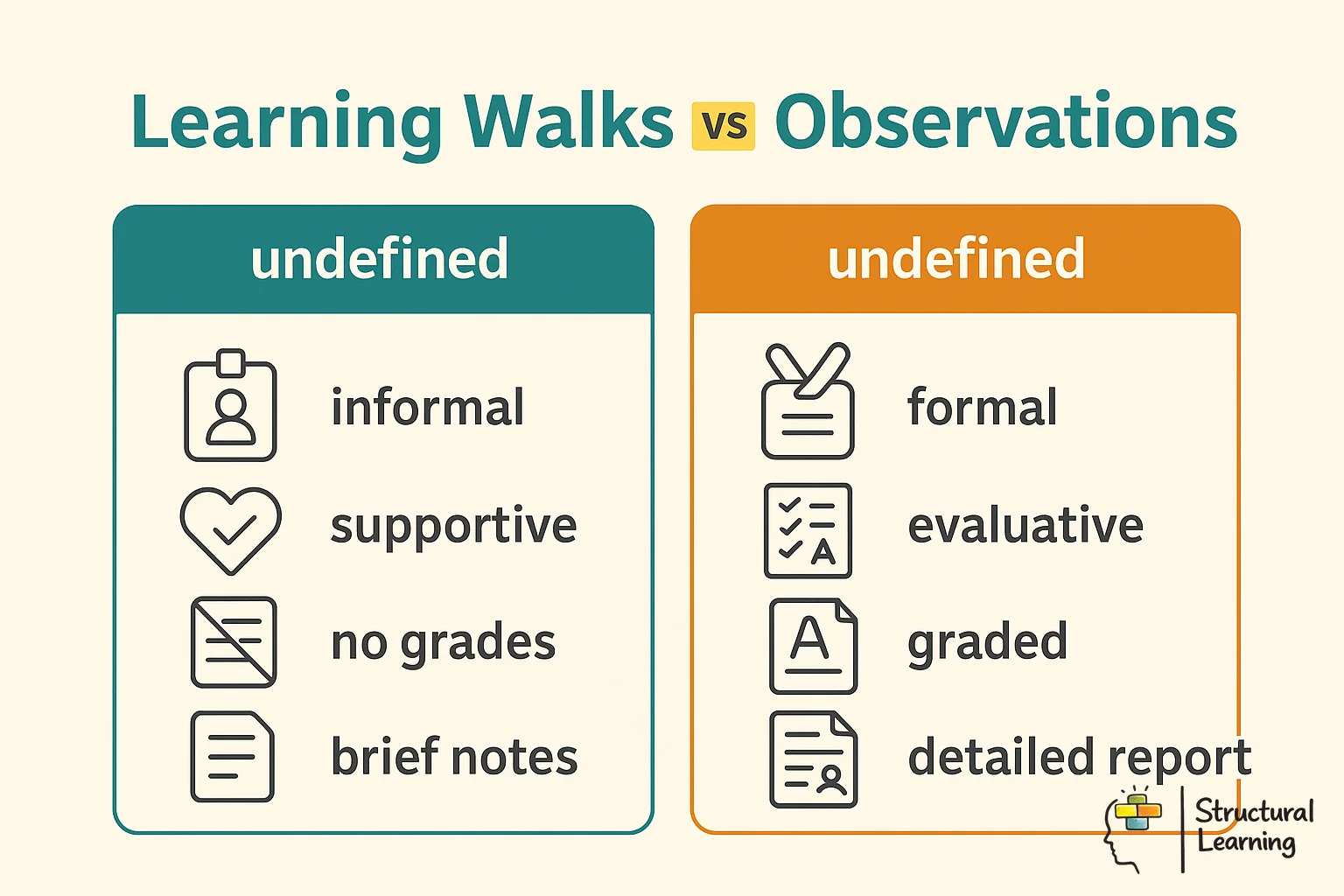

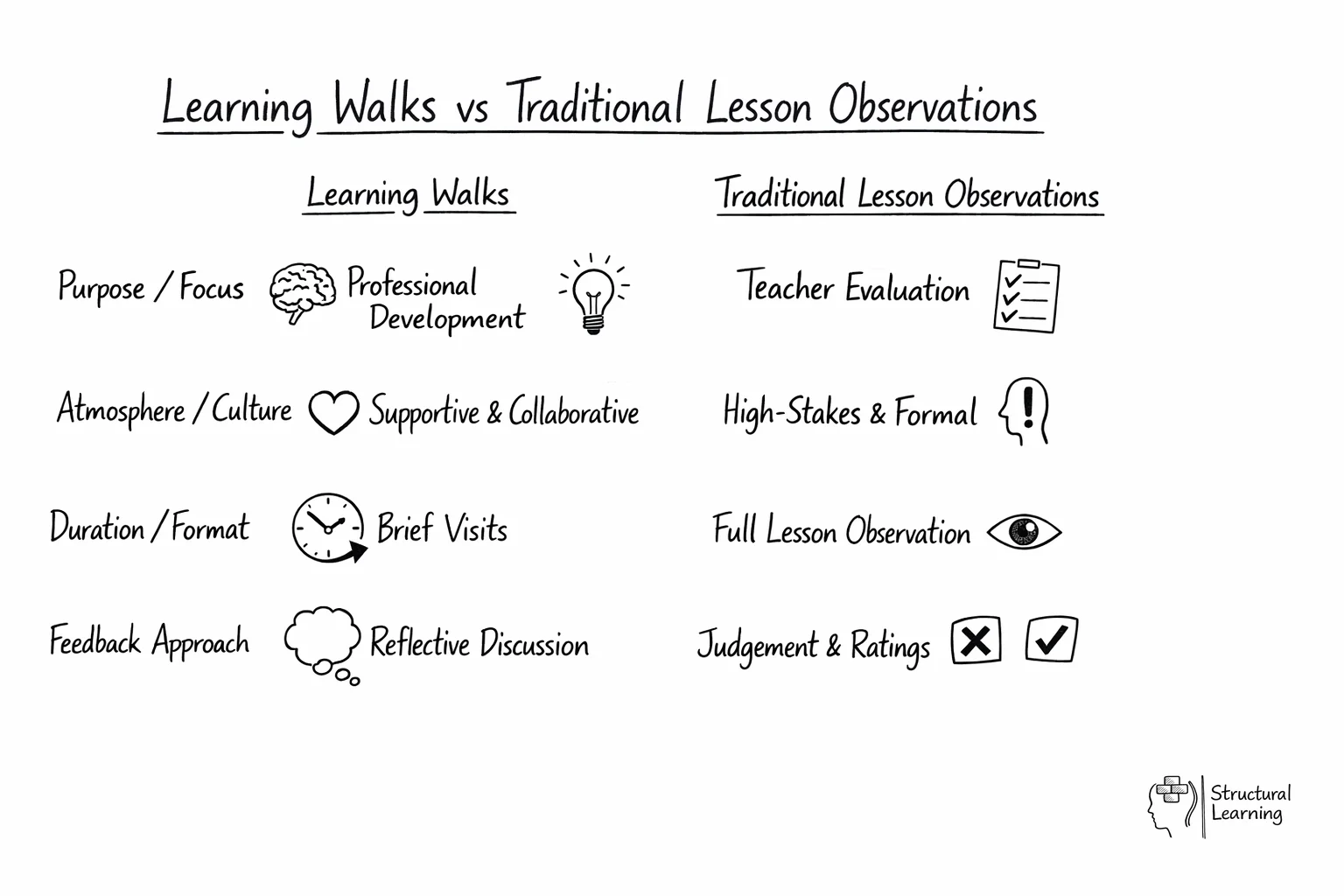

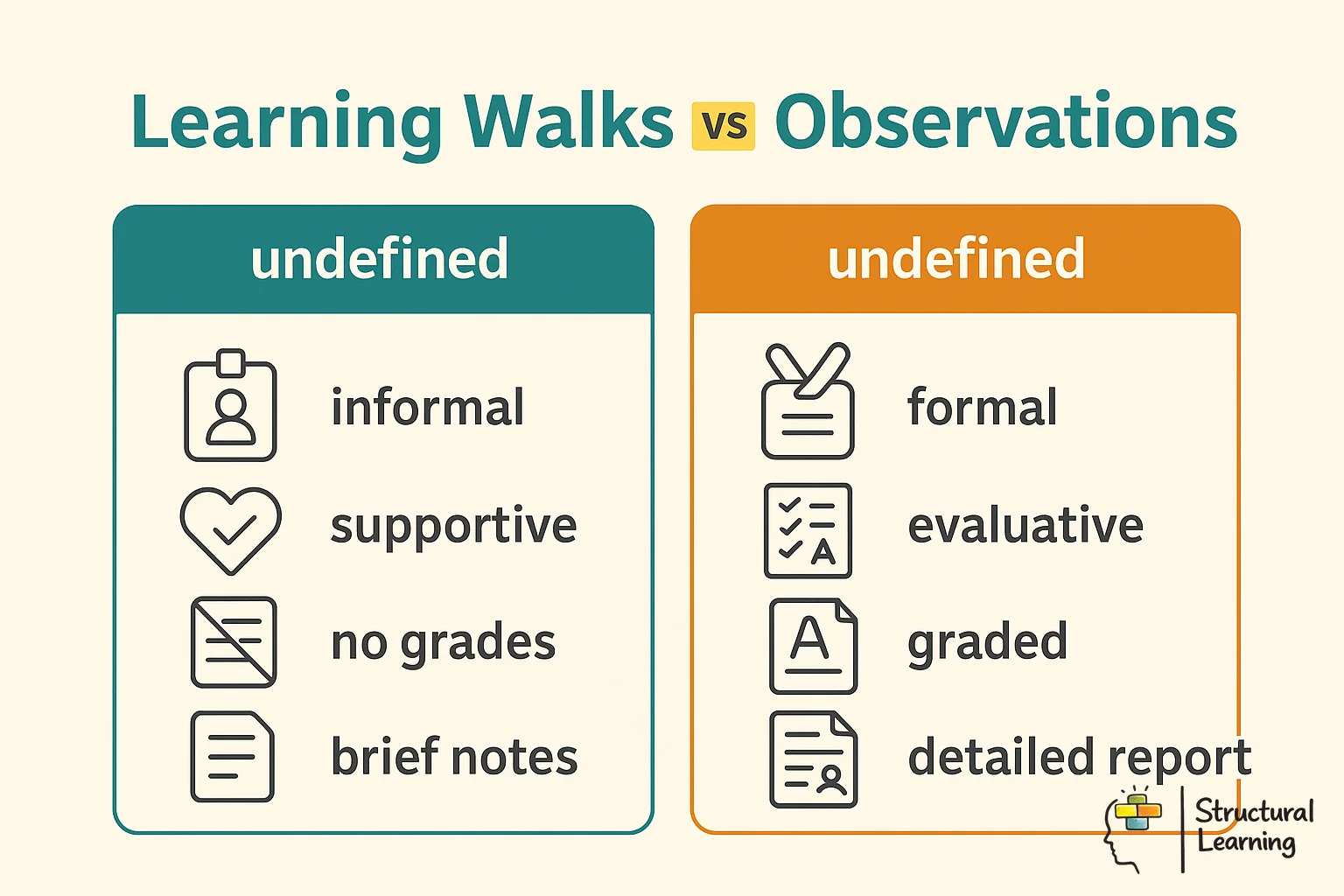

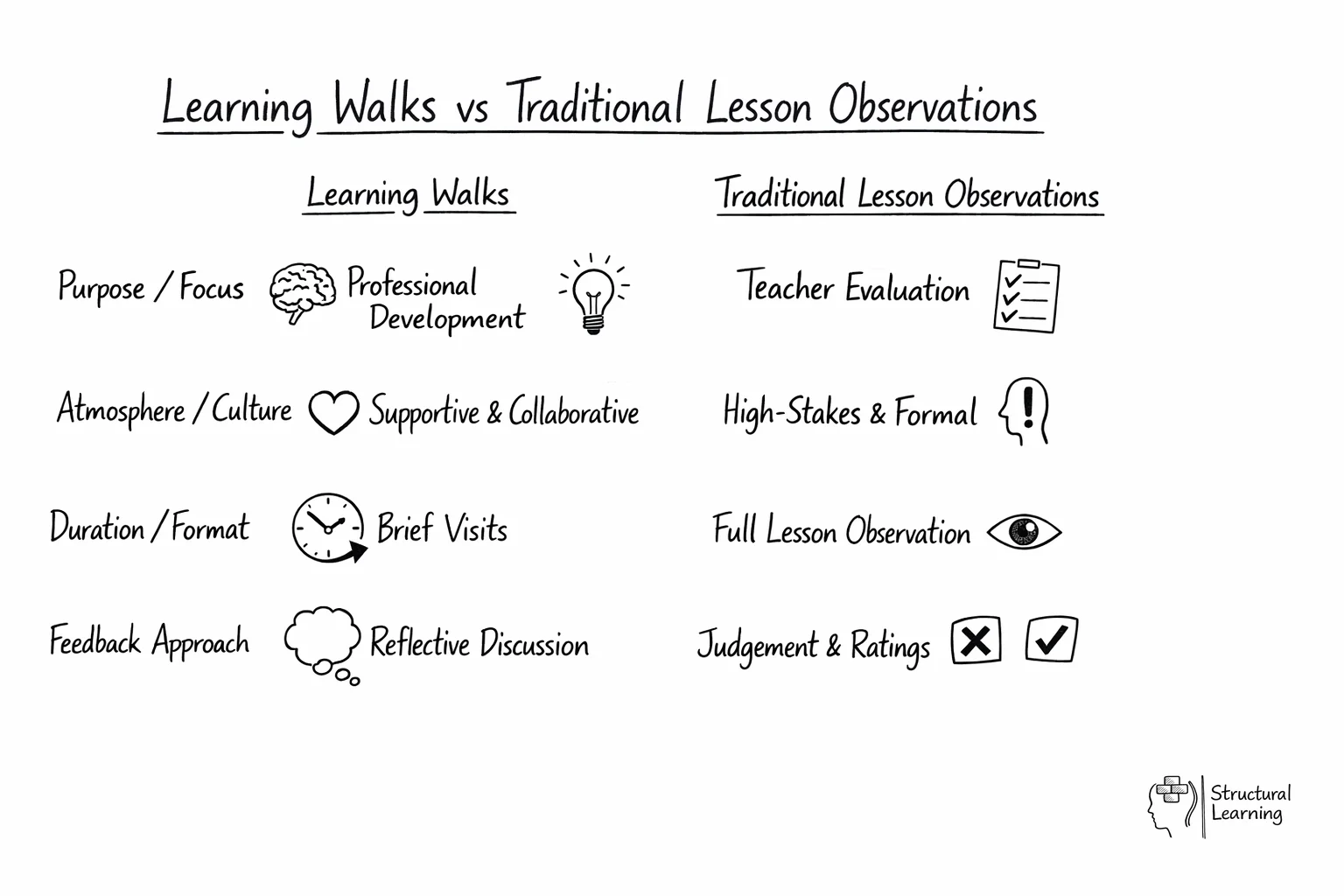

A Learning Walk is a short, focused visit to a classroom. It shifts attention away from teacher performance and toward what really matters: how students are learning. Rather than a formal inspection, it is a chance to see how pupils engage with ideas and content.

When done well, Learning Walks spark professional conversations. Teachers can reflect on their choices and share what works. It is about understanding how thinking unfolds in real classrooms, not ticking boxes.

Traditional lesson observations can feel stressful. Teachers may feel they must stage a perfect lesson. A Learning Walk removes that pressure. It focuses on what learners are actually doing: how they work with concepts and engage with information.

One of the best parts is the chance for quick, grounded feedback. Teachers can have immediate professional conversations about what was noticed and what could be improved. It is a shared inquiry, not a performance review.

What matters most is whether children are grappling with ideas in meaningful ways. Are they making l inks and scaffolding learning? That is the real measure of classroom quality.

There is no substitute for being in the room. Watching how learning unfolds offers insights that no document can provide. For school leaders, Learning Walks help gather real dataabout what is working and where support is needed.

These short visits form the baseline for school development. They help teams understand current practice and build a picture of how teaching strategies play out. But the real power lies in the conversations they spark between teachers.

For teachers who observe, it is a chance to compare approaches and reflect on their ownpractice. The follow-up discussions are where professional growth happens. Teachers return with fresh ideas to try.

Key benefits include:

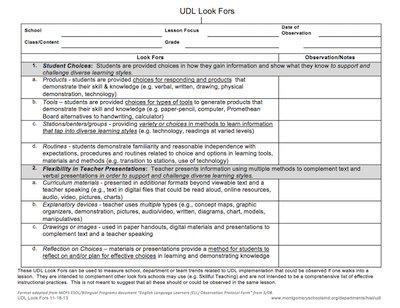

A Learning Walk is not about catching people out. It is about paying close attention to what is happening in the classroom. These short observations help leaders focus on specific elements of teaching and learning.

Leaders assess how lesson content matches curriculum expectations. Key questions include:

This focuses on how students take part. Observers ask:

The physical layout matters for learning. Observers look at:

Lessons should have clear goals. Observers ask:

Observers gather evidence on how well students are progressing:

After the walk, observers discuss what they saw. This is key for improving practice. The focus is on growth, not evaluation.

Teachers reflect on their own practice:

Effective learning walks also examine the learning environment itself. This includes checking whether classroom displays support current learning objectives, if resources are accessible and well-organised, and whether the physical space promotes collaboration or independent work as appropriate. School leaders should observe how technology is being integrated meaningfully into lessons, rather than simply being present in the room.

Additionally, observers should note evidence of differentiation and inclusive practices. Are all students appropriately challenged? How are different learning needs being met? Look for visual supports for learners with additional needs, evidence of scaffolding for less confident pupils, and extension activities for those ready to progress further. These observations help identify where additional support or training might be beneficial.

During classroom observations, focus on student engagement levels and learning behaviours. Are pupils actively participating in discussions? Do they demonstrate understanding through questioning or peer collaboration? Effective learning walks capture these authentic moments of learning, providing valuable insights that contribute to whole-school improvement rather than isolated feedback sessions.

To get the most out of Learning Walks, schools need a clear process. Here are the key steps:

Remember, the goal is to improve teaching and learning, not to find fault. Frame feedback constructively and focus on what can be done differently next time. Encourage open dialogue and shared problem-solving.

Effective Learning Walks need strong leadership. Leaders should champion the process and model a growth mindset. They must creates trust and create a safe space for honest reflection.

Successful learning walks begin long before school leaders enter the classroom. Clear preparation sets the foundation for meaningful observations that support rather than scrutinise teaching practice. Establish specific objectives for each walk, whether focusing on questioning techniques, student engagement, or curriculum implementation. This targeted approach, supported by Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment, ensures observations yield practical findings rather than superficial judgements.

Communication with staff proves crucial for creating a supportive observation culture. Share the learning walk schedule in advance, clearly explaining the purpose and focus areas. Emphasise that these visits are developmental opportunities rather than performance management exercises. When teachers understand the collaborative nature of learning walks, they become more receptive to feedback and willing to engage in professional dialogue about their practice.

Consider the timing and logistics carefully to minimise disruption whilst maximising learning opportunities. Schedule walks during different parts of lessons to observe various teaching phases, from lesson openings to plenary sessions. Plan for brief, focused visits of 10-15 minutes that capture authentic classroom interactions. Most importantly, prepare mentally to observe with curiosity rather than judgement, creating conditions where both teachers and school leaders can learn from the experience.

The true value of learning walks lies not in the observation itself, but in the purposeful actions that follow. Effective follow-up transforms fleeting classroom visits into powerful catalysts for school improvement, ensuring that insights gained translate into meaningful changes in teaching practice and learning outcomes.

Timely feedback forms the cornerstone of successful follow-up procedures. School leaders should aim to share observations with teachers within 48 hours, focusing on specific, practical points rather than generalised comments. This approach aligns with John Hattie's research on feedback effectiveness, which demonstrates that precise, timely input significantly enhances professional development. Consider establishing brief, informal conversations alongside more structured feedback sessions, allowing teachers to reflect on observations whilst the experience remains fresh in their minds.

Moving beyond individual feedback, effective learning walks should inform broader school improvement strategies. Collate observations to identify patterns across departments, year groups, or teaching approaches, using these insights to shape professional development priorities and resource allocation. Create action plans with clear timescales and success criteria, ensuring that follow-up learning walks can measure progress against identified areas for development. This cyclical approach transforms learning walks from isolated events into integral components of your school's continuous improvement culture.

The most damaging mistake school leaders make is conducting learning walks without clear purpose or prior communication with staff. When teachers perceive visits as unannounced inspections rather than supportive observations, defensive behaviours emerge that undermine the entire process. Research by Dylan Wiliam consistently shows that fear-based evaluation inhibits teacher reflection and growth, making it essential to establish psychological safety before beginning any observation programme.

Another critical pitfall involves focusing solely on performance deficits rather than celebrating effective practice. Leaders who enter classrooms looking for problems create a culture of anxiety that stifles innovation and risk-taking. Instead, effective learning walks should maintain a 70-30 balance between recognising strengths and identifying development opportunities. This approach builds teacher confidence whilst still driving improvement.

Finally, many school leaders fail to provide meaningful follow-up after learning walks, leaving teachers uncertain about next steps. Brief conversations immediately following observations, coupled with written feedback within 24 hours, demonstrate genuine commitment to teacher development. Without this structured response, learning walks become meaningless exercises that consume time without delivering tangible benefits for either teaching quality or student outcomes.

The foundation of effective learning walks lies in establishing trust and transparency from the outset. School leaders must clearly communicate that these observations are developmental rather than evaluative, focusing on understanding teaching and learning rather than making judgements about teacher performance. When staff perceive learning walks as punitive or threatening, defensive behaviours emerge that undermine the very purpose of the process. Creating psychological safety, as highlighted by Amy Edmondson's research, enables teachers to engage authentically with the feedback process and view observers as collaborative partners in their professional growth.

Successful implementation requires consistent messaging about purpose and process across all stakeholders. Senior leaders should model the collaborative approach by inviting observations of their own practice and sharing insights from their learning walks in staff meetings. Regular dialogue about observations helps normalise the process and demonstrates commitment to whole-school improvement rather than individual accountability. When teachers understand that learning walks contribute to broader school development initiatives and curriculum enhancement, they become active participants rather than passive subjects of scrutiny.

Practical steps include involving teachers in developing observation criteria, providing advance notice of focus areas, and ensuring immediate post-observation conversations remain constructive and forward-looking. This approach transforms learning walks from isolated events into integral components of your school's continuous improvement culture.

Learning Walks offer a powerful alternative to traditional lesson observations. They shift the focus from teacher performance to student learning, developing a culture of inquiry and continuous improvement. By providing timely, relevant feedback, Learning Walks helps teachers to refine their practice and enhance student outcomes.

When implemented thoughtfully and collaboratively, Learning Walks can be a catalyst for positive change within a school. They promote professional dialogue, encourage self-reflection, and ultimately, lead to a more engaging and effective learning environment for all students. Embrace the Learning Walk approach, and watch your school community thrive.

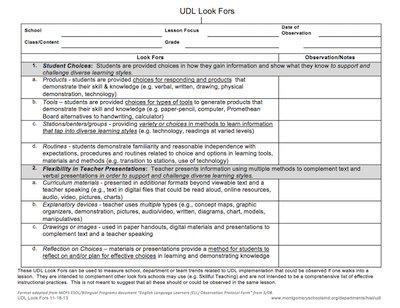

Classroom observation protocols

A Learning Walk is a short, focused visit to a classroom. It shifts attention away from teacher performance and toward what really matters: how students are learning. Rather than a formal inspection, it is a chance to see how pupils engage with ideas and content.

When done well, Learning Walks spark professional conversations. Teachers can reflect on their choices and share what works. It is about understanding how thinking unfolds in real classrooms, not ticking boxes.

Traditional lesson observations can feel stressful. Teachers may feel they must stage a perfect lesson. A Learning Walk removes that pressure. It focuses on what learners are actually doing: how they work with concepts and engage with information.

One of the best parts is the chance for quick, grounded feedback. Teachers can have immediate professional conversations about what was noticed and what could be improved. It is a shared inquiry, not a performance review.

What matters most is whether children are grappling with ideas in meaningful ways. Are they making l inks and scaffolding learning? That is the real measure of classroom quality.

There is no substitute for being in the room. Watching how learning unfolds offers insights that no document can provide. For school leaders, Learning Walks help gather real dataabout what is working and where support is needed.

These short visits form the baseline for school development. They help teams understand current practice and build a picture of how teaching strategies play out. But the real power lies in the conversations they spark between teachers.

For teachers who observe, it is a chance to compare approaches and reflect on their ownpractice. The follow-up discussions are where professional growth happens. Teachers return with fresh ideas to try.

Key benefits include:

A Learning Walk is not about catching people out. It is about paying close attention to what is happening in the classroom. These short observations help leaders focus on specific elements of teaching and learning.

Leaders assess how lesson content matches curriculum expectations. Key questions include:

This focuses on how students take part. Observers ask:

The physical layout matters for learning. Observers look at:

Lessons should have clear goals. Observers ask:

Observers gather evidence on how well students are progressing:

After the walk, observers discuss what they saw. This is key for improving practice. The focus is on growth, not evaluation.

Teachers reflect on their own practice:

Effective learning walks also examine the learning environment itself. This includes checking whether classroom displays support current learning objectives, if resources are accessible and well-organised, and whether the physical space promotes collaboration or independent work as appropriate. School leaders should observe how technology is being integrated meaningfully into lessons, rather than simply being present in the room.

Additionally, observers should note evidence of differentiation and inclusive practices. Are all students appropriately challenged? How are different learning needs being met? Look for visual supports for learners with additional needs, evidence of scaffolding for less confident pupils, and extension activities for those ready to progress further. These observations help identify where additional support or training might be beneficial.

During classroom observations, focus on student engagement levels and learning behaviours. Are pupils actively participating in discussions? Do they demonstrate understanding through questioning or peer collaboration? Effective learning walks capture these authentic moments of learning, providing valuable insights that contribute to whole-school improvement rather than isolated feedback sessions.

To get the most out of Learning Walks, schools need a clear process. Here are the key steps:

Remember, the goal is to improve teaching and learning, not to find fault. Frame feedback constructively and focus on what can be done differently next time. Encourage open dialogue and shared problem-solving.

Effective Learning Walks need strong leadership. Leaders should champion the process and model a growth mindset. They must creates trust and create a safe space for honest reflection.

Successful learning walks begin long before school leaders enter the classroom. Clear preparation sets the foundation for meaningful observations that support rather than scrutinise teaching practice. Establish specific objectives for each walk, whether focusing on questioning techniques, student engagement, or curriculum implementation. This targeted approach, supported by Dylan Wiliam's research on formative assessment, ensures observations yield practical findings rather than superficial judgements.

Communication with staff proves crucial for creating a supportive observation culture. Share the learning walk schedule in advance, clearly explaining the purpose and focus areas. Emphasise that these visits are developmental opportunities rather than performance management exercises. When teachers understand the collaborative nature of learning walks, they become more receptive to feedback and willing to engage in professional dialogue about their practice.

Consider the timing and logistics carefully to minimise disruption whilst maximising learning opportunities. Schedule walks during different parts of lessons to observe various teaching phases, from lesson openings to plenary sessions. Plan for brief, focused visits of 10-15 minutes that capture authentic classroom interactions. Most importantly, prepare mentally to observe with curiosity rather than judgement, creating conditions where both teachers and school leaders can learn from the experience.

The true value of learning walks lies not in the observation itself, but in the purposeful actions that follow. Effective follow-up transforms fleeting classroom visits into powerful catalysts for school improvement, ensuring that insights gained translate into meaningful changes in teaching practice and learning outcomes.

Timely feedback forms the cornerstone of successful follow-up procedures. School leaders should aim to share observations with teachers within 48 hours, focusing on specific, practical points rather than generalised comments. This approach aligns with John Hattie's research on feedback effectiveness, which demonstrates that precise, timely input significantly enhances professional development. Consider establishing brief, informal conversations alongside more structured feedback sessions, allowing teachers to reflect on observations whilst the experience remains fresh in their minds.

Moving beyond individual feedback, effective learning walks should inform broader school improvement strategies. Collate observations to identify patterns across departments, year groups, or teaching approaches, using these insights to shape professional development priorities and resource allocation. Create action plans with clear timescales and success criteria, ensuring that follow-up learning walks can measure progress against identified areas for development. This cyclical approach transforms learning walks from isolated events into integral components of your school's continuous improvement culture.

The most damaging mistake school leaders make is conducting learning walks without clear purpose or prior communication with staff. When teachers perceive visits as unannounced inspections rather than supportive observations, defensive behaviours emerge that undermine the entire process. Research by Dylan Wiliam consistently shows that fear-based evaluation inhibits teacher reflection and growth, making it essential to establish psychological safety before beginning any observation programme.

Another critical pitfall involves focusing solely on performance deficits rather than celebrating effective practice. Leaders who enter classrooms looking for problems create a culture of anxiety that stifles innovation and risk-taking. Instead, effective learning walks should maintain a 70-30 balance between recognising strengths and identifying development opportunities. This approach builds teacher confidence whilst still driving improvement.

Finally, many school leaders fail to provide meaningful follow-up after learning walks, leaving teachers uncertain about next steps. Brief conversations immediately following observations, coupled with written feedback within 24 hours, demonstrate genuine commitment to teacher development. Without this structured response, learning walks become meaningless exercises that consume time without delivering tangible benefits for either teaching quality or student outcomes.

The foundation of effective learning walks lies in establishing trust and transparency from the outset. School leaders must clearly communicate that these observations are developmental rather than evaluative, focusing on understanding teaching and learning rather than making judgements about teacher performance. When staff perceive learning walks as punitive or threatening, defensive behaviours emerge that undermine the very purpose of the process. Creating psychological safety, as highlighted by Amy Edmondson's research, enables teachers to engage authentically with the feedback process and view observers as collaborative partners in their professional growth.

Successful implementation requires consistent messaging about purpose and process across all stakeholders. Senior leaders should model the collaborative approach by inviting observations of their own practice and sharing insights from their learning walks in staff meetings. Regular dialogue about observations helps normalise the process and demonstrates commitment to whole-school improvement rather than individual accountability. When teachers understand that learning walks contribute to broader school development initiatives and curriculum enhancement, they become active participants rather than passive subjects of scrutiny.

Practical steps include involving teachers in developing observation criteria, providing advance notice of focus areas, and ensuring immediate post-observation conversations remain constructive and forward-looking. This approach transforms learning walks from isolated events into integral components of your school's continuous improvement culture.

Learning Walks offer a powerful alternative to traditional lesson observations. They shift the focus from teacher performance to student learning, developing a culture of inquiry and continuous improvement. By providing timely, relevant feedback, Learning Walks helps teachers to refine their practice and enhance student outcomes.

When implemented thoughtfully and collaboratively, Learning Walks can be a catalyst for positive change within a school. They promote professional dialogue, encourage self-reflection, and ultimately, lead to a more engaging and effective learning environment for all students. Embrace the Learning Walk approach, and watch your school community thrive.

Classroom observation protocols

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-walks-a-guide-for-school-leaders#article","headline":"Learning Walks: A guide for school leaders","description":"Explore how Learning Walks support school improvement by focusing on student learning, collaboration, and reflective practice.","datePublished":"2021-11-19T17:09:25.110Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-walks-a-guide-for-school-leaders"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/696a6167a6f9ee9f7cfdc5d6_696a61659002630b607a1c8d_learning-walks-a-guide-for-school-leaders-infographic.webp","wordCount":2173},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-walks-a-guide-for-school-leaders#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Learning Walks: A guide for school leaders","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/learning-walks-a-guide-for-school-leaders"}]},{"@type":"FAQPage","mainEntity":[{"@type":"Question","name":"What is a Learning Walk?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A Learning Walk is a short, focused visit to a classroom. It shifts attention away from teacher performance and toward what really matters: how students are learning. Rather than a formal inspection, it is a chance to see how pupils engage with ideas and content."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"Why do we use Learning Walks?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"There is no substitute for being in the room. Watching how learning unfolds offers insights that no document can provide. For school leaders, Learning Walks help gather real dataabout what is working and where support is needed."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"What do we look for during a Learning Walk?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"A Learning Walk is not about catching people out. It is about paying close attention to what is happening in the classroom. These short observations help leaders focus on specific elements of teaching and learning."}},{"@type":"Question","name":"How do we conduct effective Learning Walks?","acceptedAnswer":{"@type":"Answer","text":"To get the most out of Learning Walks, schools need a clear process. Here are the key steps:"}}]}]}